Meanwhile, on the other side of the country, legislators in Washington state were embroiled in a charged political budget battle over rural water rights. The lawmakers couldn’t agree on how to fix the problem of who had the right to dig new wells. The impasse lasted a nasty six months, but few people outside the state even heard about the freeze on spending it caused.

That’s because while New Jersey’s budget standoff was immediately felt by all state residents, Washington’s battle merely held up the state’s capital budget. While capital budgets are incredibly important for job growth and a state’s economy, in most places holding one hostage doesn’t cause a government shutdown. Hitting the pause button on spending to build roadways and school buildings doesn’t have the same impact as closing a public beach on a hot summer day.

New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie and his family had a state beach to themselves during a government shutdown in 2017. (AP)

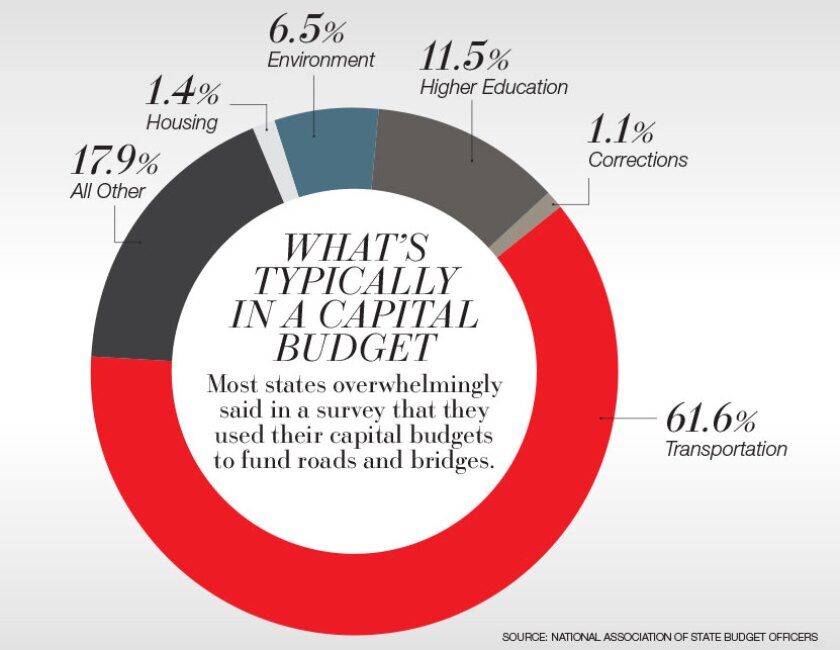

While operating budgets take care of daily expenses like personnel and office supplies, capital budgets pay for more permanent items. In essence, they are construction budgets with funding for anything from major projects like roads and bridges, on down to local parks and arts facilities. No two states have the same rules for their capital budgets. For instance, 19 states have a separate capital plan for transportation projects, according to a survey by the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO). Only 29 states include information technology, which has a much shorter shelf life than buildings and roads, in their capital plans. And roughly half of states mandate that assets their capital budget invests in must be of a physical nature.

For years, legislating and ironing out capital budgets was reserved for technical experts -- like, say, those who know how to calculate the net present value of a project. But increasingly, they are being held captive in political battles. Growing fixed costs in the operating budget, such as retiree pensions, have made state annual spending plans less flexible. It’s hardly surprising, then, that the traditionally lower-profile capital budget is becoming a tempting place to achieve new policy goals. “It’s a way to shift the political battlefield to something that still matters a lot to people,” says Justin Marlowe, a public finance professor at the University of Washington and a Governing columnist, “but not in a way that results in as many angry calls from constituents.”

This is a notable swing away from the bipartisan origins of capital budgets. Because they are essentially a long list of projects, capital budgets have traditionally been a place where political horse-trading gets done. Both sides of the aisle benefit from the projects and the spending. In short, there has always been something for everyone.

While the fight in Washington state is an unusual example, it is not the only one that suggests capital budgets are becoming increasingly policy oriented. Health-care and education initiatives that may have once been funded through the operating budget are now popping up in capital budgets. In Delaware this year, lawmakers inked a deal in the capital budget to allocate $15 million to help improve education outcomes in five struggling schools in Wilmington. In Ohio, lawmakers over the past two years have allotted more than $300 million through the capital budget to fund critical health and human services for developmental disabilities, mental health, addiction treatment and women’s health initiatives. The effort is part of an attempt to stem the state’s overwhelming number of opioid overdose deaths.

For what it’s worth, Ohio’s definition of a capital expenditure is anything with a useful life of longer than five years and at a cost of more than $500. Arguably, the opioid crisis fits that meaning. But it’s a gray area -- and one legislatures are crossing into more and more.

Turning the capital budget into yet another political football, however, is a dangerous game. Take infrastructure investment, which absent any federal action is increasingly falling upon states and localities. Inserting partisan politics into what has historically been a nonpartisan, massive economic engine for states could have uncomfortable consequences.

The origins of Washington state’s capital budget battle lay in a 2016 state Supreme Court decision that halted the drilling of private water wells for homes in rural areas. In that decision, the court ruled that counties could no longer rely on the state Department of Ecology to determine if there was enough water for new wells. Instead, localities would have to figure out if a new private well could be drilled without affecting water available to those with existing water rights, including cities and other homeowners. Counties also had to protect local streams’ fish runs and the treaty rights of the state’s tribes. This was an overwhelming alteration to the way things had been done. It resulted in a stop work order for property owners looking to drill wells for their homes.

Private wells are much more common in less-populated areas, and the decision dealt a blow to rural Washingtonians. It was an emotional time, recalls Carl Schroeder, government relations advocate for the Association of Washington Cities. He remembers one particular moment at a legislative hearing. A resident came in to testify and got down on his knees to beg legislators to come up with a fix. The man told legislators he had sold his home to his mother, bought a piece of land and was in the process of building a new home. But the decision prevented him from digging a well to finish construction. “So he was living in a trailer on his former property with his five kids and wife,” Schroeder says, “and making loan payments on a property he wasn’t able to do anything with.”

In 2017, after months of haggling over the issue, Republicans decided to take a stand in the state Senate where they held a one-vote majority. Seizing on the 60 percent majority requirement to approve bond issuances, they vowed to tie up approving any new capital spending until the water issue was decided. So, the state started fiscal 2018 without its two-year, $4.2 billion capital budget.

To many, it was a surprising turn of events. “[The capital budget has] so many investments … that have typically been supported by both parties,” says Schroeder. “Seeing it become a political football was different and sort of shocking to people.”

Democratic leaders at the time decried the move, saying the state’s capital budget is an economic priority and shouldn’t be delayed by political maneuvering. But Republicans countered that delaying a fix had dire economic consequences, including plummeting land values and lost jobs. Pointing to a study that found the state Supreme Court’s decision could result in as much as $6.9 billion in lost economic impact -- predominantly in rural counties -- then-Senate Majority Leader Mark Schoesler chastised Democrats for ignoring the state’s rural economy. “They like to pretend a fix doesn’t matter as much as the capital budget,” Schoesler said last fall, “but this study shows clearly that the annual negative economic impact far exceeds the cost of a temporary delay in state building projects.”

During the six-month delay -- which put the kibosh on an entire state construction season -- city newspapers published a slew of editorials calling for lawmakers to reach an agreement. Nationally, however, the issue fell under the radar.

When there are holdups on a state’s operating budget -- Illinois went more than two years without one -- there is analysis and dissection of the state and its problems by policy shops, rating agencies and the national media. State government shutdowns have their own Wikipedia pages and Twitter hashtags. But Washington state’s capital budget standoff generated little, if any, commentary from the peanut gallery. Why doesn’t a freeze of a capital budget cause the same furor? John Hicks, NASBO’s executive director, has an answer. “Whether it’s right or wrong,” he says, “there’s a perception of, ‘that can wait.’”

Bud Breakey and his family’s plan to build a house on property they own in rural Washington was put on hold by a state supreme court ruling and a subsequent budget impasse. (AP)

Washington state finally agreed on a solution -- and a freeing up of its capital spending plan -- in January when the legislature reconvened. Democrats gained control of the state Senate, and ultimately the water well solution and the construction budget were passed on a bipartisan basis. Some chalk up the impasse to an unusual situation where rural interests were able to unite on an emotional issue and hold their ground. “There are very few leverage points, and this was one of them,” says state Sen. David Frockt, vice chair of the committee that pushed the capital budget through. Still, he’s concerned about setting a precedent. “This is something we just have to navigate,” he says. “The operating budget, you can generally pass on a party-line basis if you can hold your members together. But with that 60 percent threshold [in the capital budget], we have to work with the other side.”

While nobody’s expecting more places to have showdowns like Washington state’s, the increased politicization of capital budgets threatens a key area of spending. State and local governments already foot three-quarters of the cost for public infrastructure. Inserting political fights into something that some consider the last bastion of bipartisan legislating could add pressure and delay much-needed infrastructure investment, as has already happened in Washington state.

The fact that a capital budget has usually been an oasis in a partisan desert is why Washington University’s Marlowe predicts that, rather than a politically risky government shutdown over operating budget expenditures, capital spending will increasingly become the political battleground of choice. “It’s still high impact,” he says. “The failure to pass one means infrastructure projects are not going to be done. If you’re looking to make a legislative statement that affects real people, the capital budget does that.”