President Donald Trump says the North American Free Trade Agreement has been a disaster. “It’s been very, very bad for our companies and for our workers,” he said at the Wisconsin headquarters of an automotive manufacturer this spring. “We’re going to make some very big changes or we are going to get rid of NAFTA for once and for all.”

But as the Trump administration sits down to renegotiate the 23-year-old free trade deal with Canada and Mexico, governors will be hoping for minor adjustments rather than the “very big changes” Trump has promised.

“There’s never anything wrong with taking a look. But I hope it doesn’t just go away,” Ohio Gov. John Kasich, a Republican, told “PBS NewsHour” earlier this year. “The idea they want to tweak it, look at it, talk, I’m all in favor of that.”

Trump’s tough talk wins him applause from voters who blame trade deals for shutting down factories and reducing blue-collar jobs in their neighborhoods. But most economists say that NAFTA had a small part to play in the long-term trends of globalization and automation that changed the kinds of jobs available in the U.S.

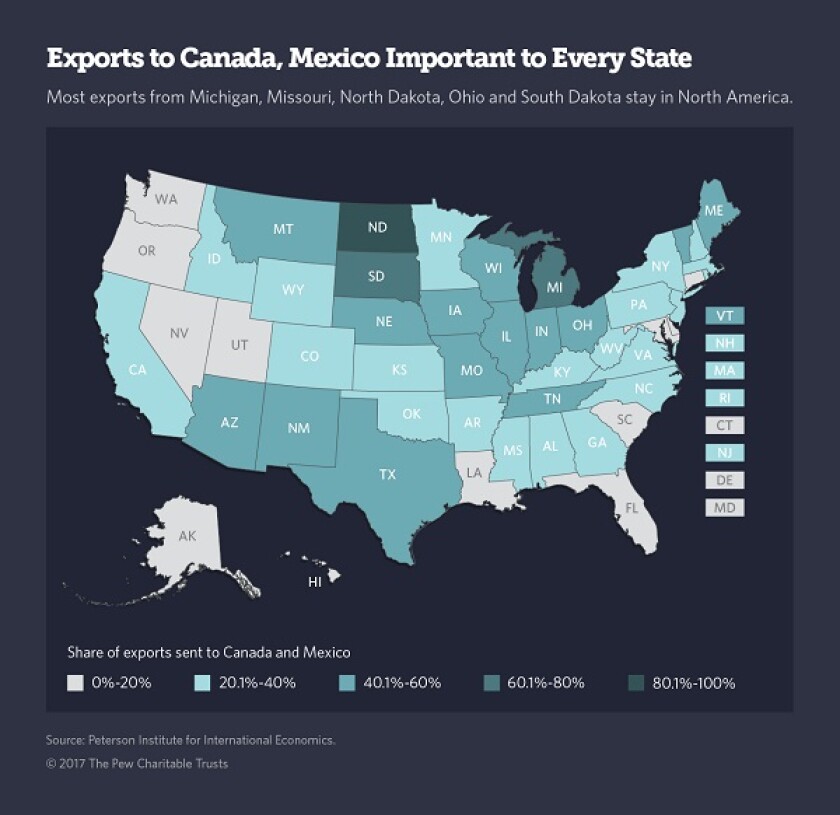

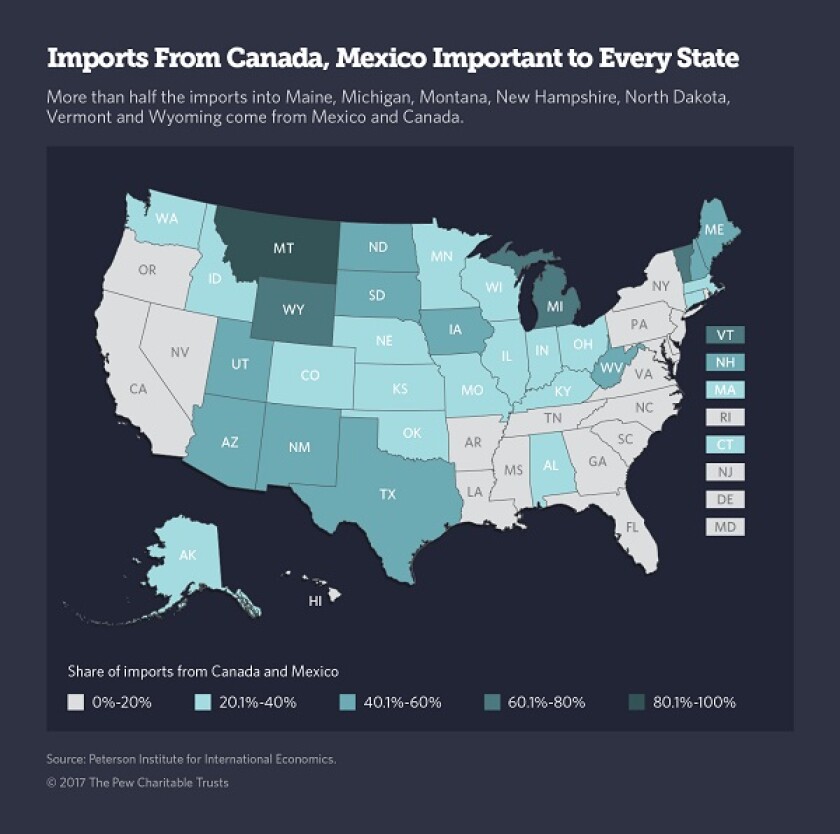

And today, trade with Canada and Mexico is important to every state’s economy. It’s boosted business for farmers in the Great Plains who export commodities such as corn, and allowed U.S. manufacturers to source parts from all over North America.

Some U.S. industries have trade disagreements with the neighboring countries to the north and south. They want those addressed in the renegotiations, but they generally don’t want the deal to be scrapped.

Governors tend to focus on how trade agreements such as NAFTA help — or hurt — specific industries in their state, says Matt Gold, a former U.S. trade negotiator who is now an adjunct professor at Fordham University. He said that focus on the nitty-gritty tends to moderate their stance.

The Trump administration’s point-by-point objectives for renegotiating NAFTA don’t go as far as the president’s rhetoric. But that hasn’t stopped businesses and foreign countries from worrying that major changes to trade policy could be pending, complicating the efforts cities and states make to recruit foreign investors and connect with international companies.

Regional Concerns

Trade boomed between the U.S., Canada and Mexico after the trade agreement took effect, in 1994, eliminating almost all tariffs on goods produced by the three nations.Last year Canada and Mexico were the top two markets for U.S. exports, combining for a third of all exports, according to the Congressional Research Service, a nonpartisan agency that advises Congress. They also comprised more than a quarter of U.S. imports.

Some sectors rely heavily on the trade deal. Take the auto industry. Today a component made in central Mexico may become part of a car assembled in South Carolina, and vice versa. And U.S. manufacturers get to export their product duty free to buyers across North America.

Carmakers say that the current system helps them compete in the global market. They don’t want the free trade agreement torn up or altered. Neither do policymakers in states that rely on auto jobs.

“We need to be very thoughtful in talking about trade issues,” Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder, a Republican, said this spring during a joint news conference with Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne. Michigan and Ontario agreed last summer to partner on efforts to make the regional auto industry more competitive, such as by collaborating on autonomous vehicle technology.

Farmers who export commodities such as corn and wheat also want to preserve the agreement. Canada, China and Mexico are the top three markets for U.S. agricultural exports, according to federal statistics.

Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts, a Republican, was in Canada on a trade mission last week talking up the importance of NAFTA. In May, he touted the agreement at a news conference alongside members of a Mexican trade delegation and U.S. grain industry leaders.

When governors criticize the trade agreement, it’s typically because they feel that a regional industry is getting a raw deal. Idaho Gov. Butch Otter, for instance, told the Idaho Statesman earlier this year that NAFTA “is a good idea, but we don’t enforce it.”

The trade agreement uses tariffs to limit sugar imports into the U.S. but Canadian sugar-rich syrups are slipping through a loophole, the Republican governor said, hurting the Idaho sugar beet industry. He also said that Canada timber policy gives its lumber companies an unfair advantage over U.S. competitors.

Democratic Govs. Tom Wolf of Pennsylvania and Andrew Cuomo of New York have sent letters to Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau asking him to stop a policy U.S. dairy producers say is hurting their ability to sell a type of skim milk in Canada. Cuomo and Republican Gov. Scott Walker of Wisconsin have also written to Trump and asked him to press Canada on the issue.

Governors are also trying to address the uncertainty Trump’s rhetoric on trade has caused by reassuring their foreign companies and investors — in North America and across the world — that they still want to work with them.

And foreign governments are also reaching out to governors. “We’ve had outreach from the international community like I’ve never seen,” said Scott Pattison, executive director of the National Governors Association. Trudeau addressed the association’s annual gathering this year, a speech he used to tout the benefits of free trade and NAFTA.

‘Mostly Baloney’

The specific objectives the Trump administration has laid out for a renegotiated NAFTA include a number of controversial points but don’t amount to a major overhaul of the agreement, experts say.A lot of the things Trump proposed as a presidential candidate, such as slapping large new tariffs on imports, would violate not just free trade agreements like NAFTA but underlying trade agreements monitored by the World Trade Organization, said Fordham University’s Gold. Both sets of deals are difficult to untangle.

“Trump’s rhetoric was mostly baloney,” he said.

Some of the administration’s proposed changes to NAFTA — such as broadening the agreement to cover digital goods and services and adding labor and environmental standards — mirror parts of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a free trade deal that the Obama administration negotiated with 11 other countries, including Mexico and Canada. One of Trump’s first acts in office was to pull the U.S. out of the deal.

Those provisions reflect the way modern trade agreements are written, trade experts say.

“NAFTA was state of the art in the early 1990s,” said Jeff Schott, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, a Washington, D.C. think tank that supports free trade, “It no longer is.”

Some of the proposed changes are opposed by U.S. manufacturers. For instance, the Trump administration wants to reassess the share of a good that has to be made in a NAFTA nation in order to be exempt from tariffs. Increasing the “rule of origin” requirement could hurt companies that have complicated international supply chains.

“The current rule of origin strikes the right balance,” American Automotive Policy Council President and former Missouri Gov. Matt Blunt testified before a United States Office of the U.S. Trade Representative committee last month.

Some proposed changes are likely to be strongly opposed by Canada and Mexico. For instance, the Trump administration wants to do away with NAFTA’s current procedure for resolving trade disputes, which has long been protested by the U.S. lumber industry.

And many changes are popular with some U.S. interest groups but not others. The Trump administration wants to shore up its “Buy American” pledge by getting rid of a rule that requires the three NAFTA governments to treat Canadian, Mexican and U.S. contractors equally in procurement decisions.

Labor unions support the change, saying allowing the U.S. government to favor U.S. companies in contracting decisions would help American workers. Meanwhile, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce opposes the change, arguing that almost all federal contracts go to domestic contractors anyway and changing the provision could end up shutting U.S. companies out of contracts with the Canadian and Mexican governments.

The biggest question is how the U.S. will try to achieve its overarching goal for the new NAFTA: reducing trade deficits with Canada and Mexico. Last year the U.S. had a $12.5 billion trade surplus with Canada and a $55.6 billion trade deficit with Mexico.

“We cannot ignore the huge trade deficits, the lost manufacturing jobs, the businesses that have closed or moved because of incentives — intended or not — in the current agreement,” said U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer in opening remarks kicking off the negotiations.

Most economists say that a trade deficit with one nation or another doesn’t really matter, although some worry about the overall national deficit. “We don’t care about how it’s distributed,” said Barry Bosworth, an economist at the Brookings Institution, a nonpartisan Washington, D.C., think tank.

And trade deals aren’t the best way to reduce the deficit, they say, because the deficit also reflects how the U.S. government and American households save and borrow money. Reducing the federal budget deficit would be a better place to start.