Some groups of workers over the past year have actually sustained notable wage declines when the numbers are adjusted for inflation. Governing identified several struggling demographic groups, using the latest quarterly median earnings estimates from the Labor Department's Current Population Survey. These groups include women with low educational attainment, older black women, black men and those with bachelor's degrees. But they also include the much broader category of employees in the prime of their working years.

Stagnant wages are partly due to inflation, which has ticked up in recent months. Inflation over the first half of the year was up 2.5 percent from 2017 and is now rising at the fastest rate since 2011-2012.

There are other plausible reasons for long-term wage stagnation. The higher wages that labor unions used to command are reaching far fewer private-sector workers than they once did. Nationally, workers are less likely to relocate for work, limiting job-movement pay raises. Some research further suggests that with big businesses employing a larger portion of the labor force, and with fewer startup companies coming on the scene, suppressed wages could be a result.

In particular, wages for many groups of women are failing to keep pace with inflation. Their real seasonally adjusted median earnings as a whole have declined or remained essentially unchanged for three consecutive quarters.

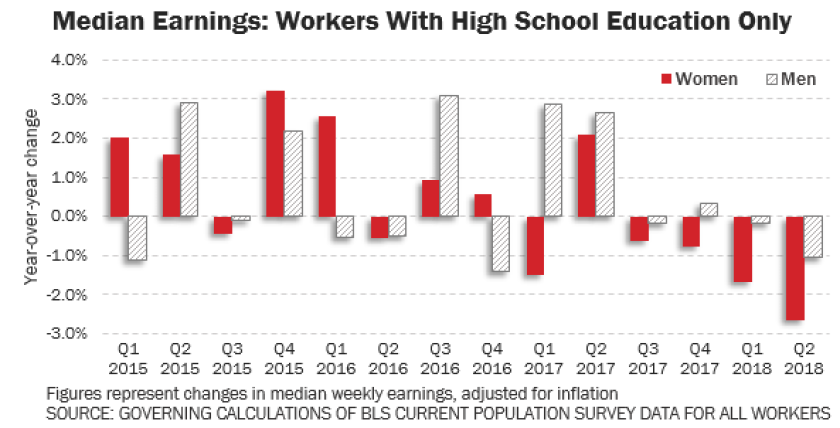

One cohort that's long struggled to secure higher wages is women with no education beyond high school. Their inflation-adjusted earnings haven't grown for any sustained period of time since 2009 in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

One possible reason, according to Chandra Childers at the Institute for Women's Policy Research, is that technology is redefining many of the jobs these workers hold in retail sales and accounting. "The threat of automation can undermine the ability of these workers to demand better pay and working conditions," she says.

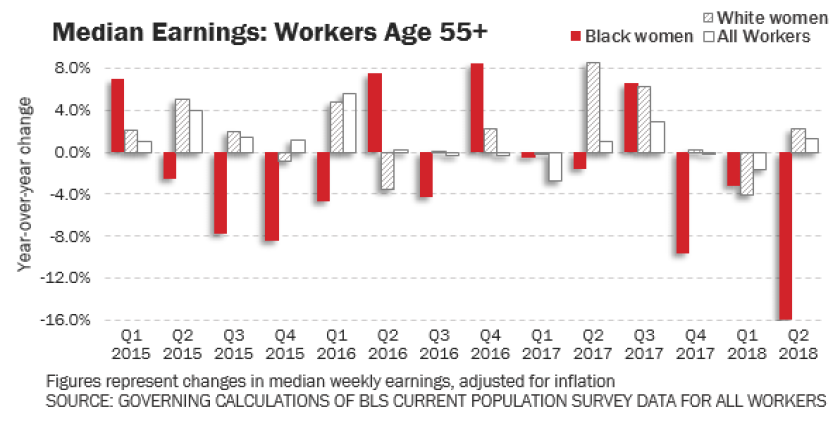

Wages of older black women also continue to fall behind. Their real earnings -- already much lower than those of other workers -- have recorded year-over-year declines for three consecutive quarters. Part of this may be because black women are overrepresented in the public sector. Many of them lost government jobs during recession-era cutbacks and haven't found employment offering the same pay and benefits.

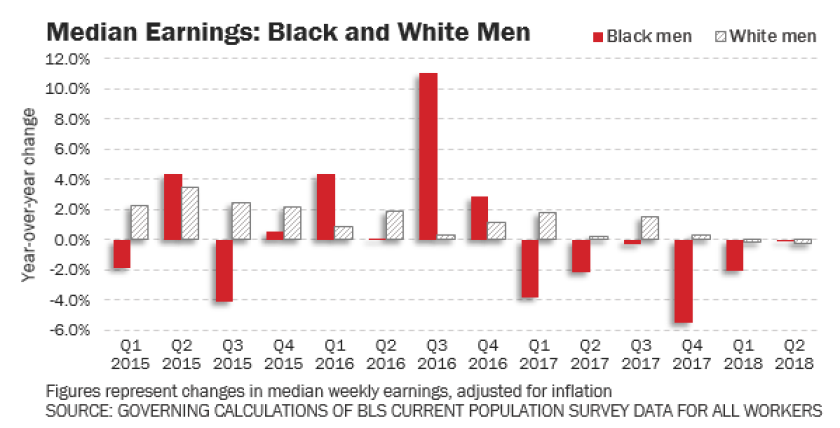

Meanwhile, wages for African-American men aren't keeping up with inflation. Their median earnings for the first half of 2018 are down 1 percent from last year and 4 percent from 2016. Although younger black workers and black men nearing retirement also aren't receiving pay raises, it's middle-aged black men who have sustained the largest losses recently.

Labor unions represented 14 percent of black workers last year, a higher number than for white or Hispanic employees, according to Labor Department estimates. Childers says it's likely that they have been particularly affected by right-to-work laws, related court decisions and unchanged minimum wages in some parts of the country.

Across different levels of education, those who left school after receiving bachelor's degrees have incurred the most noticeable decline over the past 12 months. Their year-over-year median earnings have been down for four straight quarters, with estimates for the second quarter of this year down nearly 3 percent. Wage stagnation for workers holding advanced degrees hasn't been quite as severe.

Finally, earnings for the key prime working-age segment of the labor force -- those between 25 and 54 -- also are starting to head in the wrong direction. After a sustained period of slight growth, they've turned negative the past four quarters.