OBAMACARE

(David Kidd)

The campaign slogan from Donald Trump and congressional Republicans was very simple: “repeal and replace” Obamacare. Carrying out that promise will be anything but simple. Still, Trump’s victory, combined with Republican control of Congress, virtually assures that major changes are in the works for the law that has extended health insurance coverage to more than 20 million Americans.

First off, Congress is likely to overhaul or scrap the state insurance marketplaces created under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which allow workers without employer-provided coverage to shop for insurance. Premium increases, technological problems and lack of insurer competition have made the marketplaces a sore spot for both consumers and policymakers. Congress could dismantle the exchanges altogether or ask states to take them over.

States will be keeping a close eye on the $509 billion Medicaid program, which is the single biggest budget item for most of them. Obamacare included huge financial incentives for states to expand Medicaid programs to cover more people, and 31 states took advantage of the deal. Those expansions added some 16 million citizens to the Medicaid rolls. Republican state officials have fought with the Obama administration over whether they could impose new premiums or work requirements on enrollees as part of the expansion. The incoming Congress may allow states to enact more such cost controls.

But both Trump and House Speaker Paul Ryan have supported far more sweeping proposals to change Medicaid into a block grant program to states. Rather than having states and the federal government share cost increases in the program, the feds would agree to pay a fixed and limited share and then give states more flexibility to spend the rest of their Medicaid dollars as they see fit. Although states could theoretically keep their Medicaid expansions in place under that scenario, it’s more likely that they’d limit access to control costs. “It’s hard to imagine a scenario where people aren’t going to lose their coverage,” says Timothy Jost, emeritus professor of health-care law at Washington and Lee University.

Trump has said he would try to keep the more popular aspects of the ACA in place, such as provisions requiring insurers to cover people with pre-existing conditions and allowing young people to stay on their parents’ insurance until age 26.

Trump also has championed changes that would let insurers sell health insurance plans across state lines, something that was technically allowed but never fully implemented under the ACA. The president-elect says the arrangement would spur competition. “As long as the plan purchased complies with state requirements, any vendor ought to be able to offer insurance in any state,” Trump’s transition website says. “By allowing full competition in this market, insurance costs will go down and consumer satisfaction will go up.” Critics complain, however, that states and vendors freed from regulation will compete to provide less, rather than more, when it comes to health coverage.

—Mattie Quinn

FINANCIAL STRESS

Rogelio V. Solis/AP

(AP/Rogelio V. Solis)

Just when states’ fiscal pictures were starting to look good after a slow recovery from the Great Recession, state budgets have begun to show signs of trouble again.

The first red flag is that, in much of the country, tax revenues are leveling off. A sluggish stock market and low oil prices led to weak revenue growth in 2016. State collections increased by only 1.6 percent in the first quarter of last year, and, based on preliminary data, actually dropped by 2.1 percent in the second quarter, according to the Rockefeller Institute of Government. The bad news has been driven by weaker sales tax revenues, a moderate decline in income tax receipts and a steep decline in corporate tax payments. Half the states experienced second-quarter 2016 declines, and this will make for shortfalls in some current-year budgets. Coal- and oil-producing states such as Alaska, North Dakota, Oklahoma and Wyoming have been especially hard-hit.

While the numbers across the country do not amount to “recession-sized shortfalls,” says Rockefeller’s Donald Boyd, they come at a time when state pension contribution requirements are expected to increase because of poor pension fund investment returns in recent years. On top of that, Medicaid costs are going up thanks to higher prescription drug expenses and a requirement for many states to start paying a small share of the cost of their Medicaid expansions under the ACA.

Lawmakers have no choice but to deal with the spiraling costs of health care and pensions, but addressing them puts pressure on other areas of state budgets -- such as schools and social services -- that are politically more popular. That makes the task of addressing budget shortfalls even more difficult. Legislators returning to their state capitols this winter may find they have to work on two challenges at the same time: shoring up their current budgets while drafting more conservative spending plans for next year. Connecticut, for example, faces a $650 million shortfall midway through fiscal 2017, while it needs to find about $29 million in additional Medicaid costs for the next fiscal year.

Given the Republican gains in many statehouses across the country, lawmakers will likely choose belt-tightening over tax increases to make ends meet. This means that states will have less spending flexibility to devote to new programs or priorities and will be shuffling dollars around to target policy goals. It also means states are likely to pass on some of the hurt to local governments in the form of less direct aid.

—Liz Farmer

IMMIGRATION

(Shutterstock)

Trump promised to crack down on illegal immigration by building a wall along the nation’s southern border and deporting millions who are in the country unlawfully. But within days of winning the election, he came across a stumbling block: sanctuary cities. Though no legal definition exists, a sanctuary city is a place whose laws or policies limit the cooperation of local law enforcement with federal immigration officials in searching for and detaining those who are undocumented. In New York, for example, undocumented immigrants accused of low-level nonviolent offenses aren’t turned over to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Those sanctuary protections do not extend to violent crimes.

The country has more than 330 cities with some form of sanctuary policy, and a recent estimate pegged the number of undocumented immigrants living in such jurisdictions at 5.9 million people, roughly 53 percent of the overall undocumented population. Muzaffar Chishti, an attorney with the Migration Policy Institute, says local governments and their law enforcement officials would be critical in rounding up undocumented immigrants who have committed crimes -- Trump’s stated target for deportations. “If removing criminal aliens is an important goal of the administration, then getting cooperation from the local jurisdictions becomes an important element of achieving it,” Chishti says.

Trump and his surrogates, however, have warned that they’ll cut off federal funds to sanctuary cities in the first 100 days of the new administration. It’s unclear which federal grant programs they could cut, but criminal justice grants worth hundreds of millions of dollars might be in jeopardy. The Fraternal Order of Police, which endorsed Trump last year, argues that the threatened cuts could harm public safety. Mayors in Chicago, Los Angeles and Seattle say they’re willing to forgo the funding in order to keep their current sanctuary policies. “Seattle has always been a welcoming city,” Mayor Ed Murray said in a press conference in November. “The last thing I want is for us to start turning on our neighbors.”

States and localities are likely to be affected by another immigration promise from Trump: repeal of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), the executive order by President Obama that granted more than 700,000 young undocumented immigrants temporary lawful status and relief from deportation. Among other consequences of DACA, the order made it easier for some undocumented immigrants to receive state-issued driver’s licenses. Mark Krikorian of the Center for Immigration Studies, a group that favors reduced immigration, says it’s unclear how the repeal of DACA would affect driver’s licenses. Under the Constitution and the 2005 federal REAL ID law, states are already allowed to issue an alternate form of driver’s license, often called a driver’s privilege card, to the undocumented. But most states don’t offer those cards. Under the REAL ID Act, federal agencies aren’t supposed to treat privilege cards as a valid form of identification for activities such as entering federal facilities or boarding commercial flights.

—J.B. Wogan

ZIKA

(AP)

Zika was the public health crisis that came out of nowhere in 2016. In January, there was a steady drumbeat of headlines on the staggering number of women in Latin America giving birth to babies with deformed heads. The culprit was a mild flu-like virus transmitted via mosquitoes that can cause newborns to develop microcephaly -- abnormal brain development. As the news stories grew in numbers, so did the threat that Zika could soon debut in the United States.

It didn’t take long. After several months of reports that Americans were coming down with the virus abroad, the first case of locally transmitted Zika was reported in Miami in July. Since then, at least 182 locally transmitted cases have been reported in the Miami area, and another one in Brownsville, Texas. States with warm weather climates from Texas to Maryland ramped up public information campaigns and mosquito control efforts last summer. However, many health officials complained their ability to respond to the virus was limited without help from the federal government.

Late last year, Congress approved aid to states to fight the virus after months of haggling. While the World Health Organization has downgraded Zika from a global emergency to a public health alert, the virus remains a top concern for many areas. Zika is still in America’s mosquito population, and another wave of infections is likely once the weather warms up. Armed with the federal money they asked for, state officials have explored ideas such as making mosquito repellent free for low-income populations, starting programs to repair screen doors and accelerating tests for the virus.

Meanwhile, public health officials will be watching to see if any of the 183 locally transmitted cases from last summer results in any cases of newborn microcephaly.

—Mattie Quinn

INFRASTRUCTURE SPENDING

(Shutterstock)

When it comes to infrastructure, nothing gets lawmakers’ attention quite like bad roads. And in recent years, legislators in more than a dozen states have found new revenue to fix those roads. Given the massive maintenance backlogs at many highway departments, it’s likely that more states will take a look at their road funding in 2017.

What may be different this year, though, is the prominence of infrastructure needs that extend far beyond roads. The Flint water crisis in Michigan made it painfully clear to the public that drinking water systems in many cities need major investment, especially to lower the risk of lead poisoning from old pipes. Transit in many large cities, notably San Francisco and Washington, D.C., faces daunting repair backlogs, while New York City is having to replace a subway tunnel damaged by Hurricane Sandy. Airports are under scrutiny too after decades of neglect.

Trump made the case for a wide mix of infrastructure improvements during his election night victory speech. “We are going to fix our inner cities and rebuild our highways, bridges, tunnels, airports, schools, hospitals,” the president-elect said. “We’re going to rebuild our infrastructure, which will become, by the way, second to none. And we will put millions of our people to work as we rebuild it.”

Trump’s team has floated a number of ways the federal government could help spur private investment in infrastructure, using mechanisms such as infrastructure banks, bonds and tax credits. But those may not be enough, says Bud Wright, executive director of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. “Those are nice pieces of the puzzle to have … but we need some regular old funding,” he says. “We need to see some growth in the federal program.”

It took Congress more than five years, however, to cobble together enough money to keep the federal transportation program going without a gas tax hike. Congress hasn’t raised the federal gas tax since 1993, and with both chambers under Republican control, that is unlikely to change soon.

So there will be increased pressure on state and local governments to find more infrastructure money on their own. Republicans dominate state legislatures too, but that hasn’t stopped GOP-led states such as Idaho and Utah from raising their gas taxes in recent years for transportation needs. The upcoming legislative session may be a particularly attractive time for legislators to vote on new revenues, because most lawmakers will be more than a year away from running for re-election. Low gas prices and low interest rates -- if they last -- will also make fuel taxes and bonding measures less painful than they might be in other seasons.

Meanwhile, several states are preparing to study whether they can phase out fuel taxes entirely and replace them with mileage fees. Seven states are receiving federal funds to explore this alternative.

—Daniel C. Vock

POLICING

(Shutterstock)

The biggest problem facing the nation’s police departments is that many of those they serve simply don’t trust them. So it’s likely that some legislatures will involve themselves further in local policing in an attempt to ease tensions.

Some will look at updating statutes around use-of-force incidents. In Washington state, where critics say it is nearly impossible to prosecute a police officer for killing someone, a legislative task force recommended changing state law to clear the way for those prosecutions. But any change in the standards for prosecuting police officers will likely encounter resistance from groups such as the International Association of Chiefs of Police and the Fraternal Order of Police.

The Washington task force also called for better data collection, more intensive training of police officers and improvements in the state’s mental health system. Those issues are likely to come up in numerous places. The lack of good data on shootings by police officers and on the circumstances of police stops is a problem around the country. Right now, reporting is either inconsistent or not done at all. California and a few other states have passed laws that will require law enforcement agencies to collect and report data on police stops, with other legislatures likely to soon follow suit. Body cameras, another accountability measure, will continue to proliferate after a slew of law enforcement agencies received federal funding to implement them last year.

Another growing concern is over the investigation of fatal civilian encounters with police. Minority communities and the families of victims have called for independent investigations, rather than inquiries by prosecutors who frequently work with police departments. In Ohio, a task force recommendation called for lawmakers to shift the authority for investigating police involved in shootings from county prosecutors to the state attorney general’s office.

—Mike Maciag

MARIJUANA

(Shutterstock)

Last November, voters in four states -- California, Maine, Massachusetts and Nevada -- passed measures to legalize recreational use of marijuana. Those results doubled the number of states that legalize recreational pot. Meanwhile, 30 states have made marijuana legal for medicinal purposes. All of that activity has occurred despite the fact that the federal government still classifies marijuana as an illegal substance.

The states were able to proceed because the federal government has essentially ignored the growing legalization movement. But that may not last for long. Trump’s nominee for attorney general, U.S. Sen. Jeff Sessions of Alabama, has been a vocal opponent of marijuana legalization efforts. As attorney general, he would have the ability to prosecute pot sellers, even if a state licensed them. Just threatening a crackdown could be enough to scare off investors and shut down shops. States will have to tread carefully as they look to liberalize their drug laws.

Even if legalization proceeds as planned in the four states that voted yes on marijuana, state officials will have plenty to consider. One crucial task will be to figure out just how much sales tax revenue they should plan on getting from pot sales. California, for one, expects marijuana sales tax revenue will range from the high hundreds of millions of dollars to more than $1 billion annually. Missing revenue estimates could have big consequences, but the fact that marijuana taxes are so new makes them hard to predict. That’s a lesson Colorado learned the hard way: It underestimated the amount of new revenue it would see during its first year of legalized pot sales, which, because of its Taxpayers Bill of Rights law, nearly triggered a taxpayer refund.

—Daniel C. Vock, Mattie Quinn and Liz Farmer

OPIOIDS

(AP)

The problem of opioid addiction remains a persistent one. In some states, its effects are so devastating that it is the topic of conversation at any gathering of policymakers. The number of people dying of opioid overdoses has skyrocketed in the past decade, and it continues to climb even as efforts have ramped up to combat it. More than 28,000 people died from opioid overdoses in 2014, and that number rose to approximately 33,000 in 2015.

What started as a largely white, middle-class problem in New England has spread to almost every demographic in every single state, and has broadened from prescription drugs to heroin. Governments responded aggressively in 2016 to the alarming rates of drug use, as police departments and other local agencies equipped their personnel with Narcan, the life-saving drug that reverses an overdose. Several states and cities eased restrictions on needle exchange clinics, which help slow the spread of infectious diseases among intravenous drug users. The epidemic even created a rare moment of bipartisanship: Forty-six governors signed a compact at July’s National Governors Association conference promising to do whatever possible to curb the toll opioids have taken.

—Mattie Quinn

CLEAN ENERGY

(AP)

Immediately after his election, Trump vowed to repeal several environmental regulations during his first 100 days in office. None was more important than the Clean Power Plan, a recent product of the Obama administration that would push states toward adopting cap-and-trade systems for carbon dioxide emissions from power plants.

Trump’s promise came as good news for many Republican state officials, particularly the attorneys general who have fought against the regulations in court. But repeal of the Clean Power Plan won’t be a done deal within 100 days of the inauguration; in fact, the regulatory and court battles could stretch on for years.

The Trump administration could change or repeal the plan on its own, but doing so would involve a lengthy federal regulatory process. Meanwhile, 45 of the 50 states have taken sides in a court battle over the issue. The case is now before a federal appeals court, although the Supreme Court intervened last year to block the rule while appeals continue. Environmentalists are hopeful that courts will require some limits on carbon dioxide emissions, because the Supreme Court ruled in 2007 that the federal government had to regulate greenhouse gas as a pollutant. “The law constrains the president on this, because the law puts in limits based on what the science points to,” says David Goldston, director of government affairs for the Natural Resources Defense Council. “Even if they succeeded, they would still have to do something on climate change under the Clean Air Act.”

All of this means that, for the time being, questions about clean energy will continue cropping up in state legislatures. Lawmakers could weigh in on policies designed to spur the use of solar panels in Florida, build a natural gas pipeline in Alaska and dismantle clean energy quotas for power companies in Ohio.

Meanwhile, utility commissioners still must decide whether ratepayers should pay higher electric prices for power from coal-fired electricity plants or whether utilities should be forced to use cheaper sources of energy, such as natural gas, solar and wind. Nearly half of the country’s coal-fired plants have been shuttered since 2010.

—Daniel C. Vock

SOCIAL ISSUES

(AP)

North Carolina’s Pat McCrory was beaten for re-election as governor in November, but his curtailed political career may have an influence on the way social issues play out in other states this year. The one-term Republican was the only incumbent governor in the country driven from office in 2016, and his loss was widely attributed to his approval of a bill that blocked anti-discrimination protections for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender individuals.

Advocates on both the left and the right say that McCrory’s defeat could serve as a warning to conservatives eager to push divisive social issues. “North Carolina had a very good fiscal and tax record under McCrory,” says John Nothdurft, director of government relations for the conservative Heartland Institute. “Social issues are actually what hurt him.”

Nonetheless, given the impending restoration of a conservative majority on the U.S. Supreme Court, right-leaning legislators across the country are bound to feel empowered. States will pass new restrictions on abortion, continuing to test how close the courts will let them come to imposing outright abortion bans earlier in pregnancy. Numerous states that haven’t yet cut off Medicaid funding for Planned Parenthood will attempt to do so.

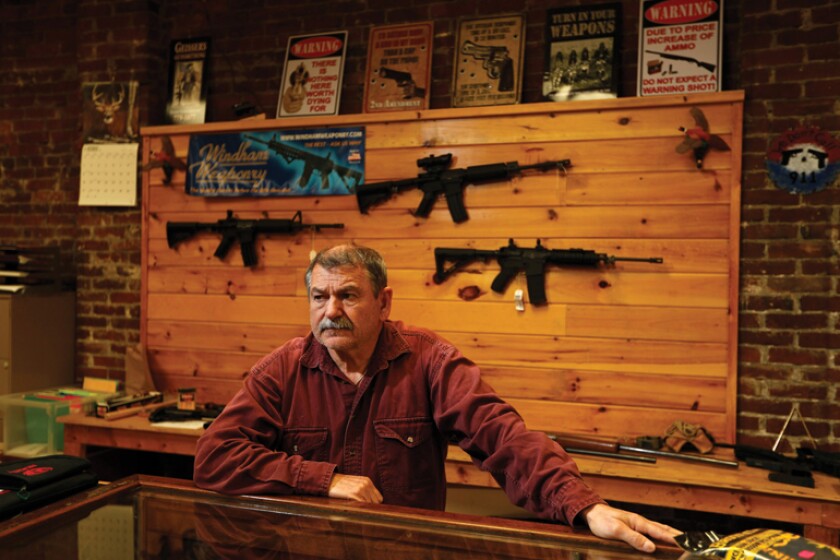

Gun owners’ rights will continue to be expanded, with conservatives calling for “constitutional carry” -- the right to carry firearms, whether concealed or not, without a permit. More states may pass laws making clear that firearms can’t be taken away during a natural disaster. Additional states could enact pre-emption laws to protect gun rights if localities attempt to pass restrictions.

The Supreme Court has already agreed to hear a case this term involving a transgender high school student who is seeking to use bathroom facilities that conform to his gender identity. Bathroom issues have been a particular trigger of late. Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, who presides over the state Senate, has already made clear his intention to push a restrictive bathroom bill this year, which he is framing as an effort to protect the privacy of women.

Pragmatic Republicans have often argued against pursuing such divisive issues, warning that they can distract from bread-and-butter debates over taxes, education and infrastructure. Those arguments may be less convincing with the change in Washington.

“Over the last few cycles, the Republican establishment has blocked or watered down some of the more divisive or controversial issues, with the argument that the Obama administration would block it, or it would fail in the courts,” says Mark Jones, a political scientist at Rice University. “It’s going to be tougher on some of those issues for the Republican leadership or the establishment leadership to rein in more conservative members of the legislature, because they’re going to view Washington as more sympathetic.”

—Alan Greenblatt

SCHOOL CHOICE

(AP)

Brian Sandoval, Nevada’s Republican governor, intends to find the money to expand school choice. In 2015, Sandoval signed legislation making his state the first to offer voucher-style education savings accounts (ESAs) to all students, regardless of geography, income level or special needs, and make them available for private as well as public education. Last fall, the state Supreme Court gave its blessing to the law, but said the funding mechanism was unconstitutional. Sandoval has pledged to include funding for ESAs in his new budget, paying for them as a separate line item to satisfy the court.

He may not win approval. Democrats took control of both of Nevada’s legislative chambers in November, and the new Democratic majority tends to view Sandoval’s program as a threat to public schools. Nevertheless, the Nevada law is one that other states have been looking at as a possible model. ESA bills will be introduced in at least a dozen states in 2017. Some states that have ESAs in place may be looking to expand their programs, perhaps even adopting Nevada’s universal approach, says Adam Peshek of the Foundation for Excellence in Education. “In most states, there will be an ESA program under consideration,” he says. “That seems to be the preferred method nowadays.”

School choice has expanded rapidly in recent years. That momentum will not be broken this year. “It’s going to be a big issue in a bunch of states,” says Andrew Rotherham, an education consultant. “Republicans tend to favor school choice and now that they control more state legislatures, it stands to reason that they’ll expand it more.” In Kentucky, where Republicans have taken control of the state House of Representatives -- and with it, the entire government -- a new law to allow charter schools in the state is almost a given, as the idea has long been a priority of Gov. Matt Bevin.

Trump’s selection of Betsy DeVos, a Michigan billionaire and longtime proponent of school vouchers, as education secretary could bring national attention to the issue as well. At the very least, with the federal government under Republican control, look for private school vouchers to expand in Washington, D.C., itself. The Obama administration fought congressional efforts to fund vouchers in the District of Columbia, and that opposition was once taken as symbolic proof that the school choice movement had lost some of its influence. Now Congress could continue using the nation’s capital as a laboratory for school choice alternatives it hopes will gain additional traction in the states.

—Alan Greenblatt

FOSTER CARE

(AP)

Half a million children are in foster care in the United States, but instead of being safely reunited with their families -- or moved quickly into adoptive homes -- many languish in public institutions for years. On average, foster children spend nearly two years in state care, and 7 percent stay at least five years. In 2014, more than 22,000 kids aged out of foster care without permanent families.

In recent years, a flurry of lawsuits driven by the New York-based advocacy group Children’s Rights has spurred major changes aimed at reducing the amount of time children spend as wards of the state. Changes so far have resulted in more adoptions, fewer kids living in institutions and significantly reduced caseloads for child welfare workers in Connecticut, South Carolina and Tennessee, among other jurisdictions. Some places currently under judicial order are poised to emerge from court oversight in 2017.

The biggest foster care reform is likely to come in Texas, where 12,000 children are currently living in institutions. A federal judge has called the state’s foster care a “broken” system, in which “rape, abuse, psychotropic medication and instability are the norm.” Texas is under a mandate to overhaul its system, which, unlike other states, gives caseworkers only 18 months to reunify children with their birth families or find them adoptive homes before they enter permanent foster care.

A shortage of funding and foster parents in Texas has led to hundreds of children having to sleep in state office buildings. Directed to impose many of the same reforms now being implemented in other states, Texas lawmakers will face intense pressure to deal with the crisis this year.

—Liz Farmer

HIGHER EDUCATION

(Shutterstock)

The cost of tuition at public four-year institutions has gone up, on average, 2.8 percent a year for the last decade, even as wages for most Americans have remained stagnant. Universities have had to rely on tuition increases in large part because of cuts in state spending on higher education. In a few places, funding still isn’t at the level of a decade ago. But the last three years have seen incremental increases in spending in most states, and if local economies continue to improve, those increases are likely to continue. “Whenever there is a reduction in spending, it’s always tied to a recession,” says Dustin Weeden, an analyst with the National Conference of State Legislatures. “When states have increasing revenue, they often reinvest in education.”

While an increase in overall spending could make college more affordable for everybody, some states have already sought to use their limited tax dollars to reduce the cost of college for low-income residents. In the past few years, Tennessee, Oregon and Minnesota have enacted laws creating free community college for students whose federal financial aid doesn’t cover all of their tuition. At least 10 other states considered similar legislation in the last session and could take up the issue again. The most interesting state to watch will be Kentucky.

Last year, Kentucky passed legislation and appropriated money for a free community college program similar to the one in Tennessee. Republican Gov. Matt Bevin vetoed the legislation for the 2016-2017 academic year, but that left room for the program to be revived by lawmakers in 2017. Bevin said he supported the concept but had concerns about the law’s design, including a broad eligibility provision that could have resulted in state scholarships covering tuition at expensive four-year universities and private institutions. It’s unclear how likely the legislature is to pass a revised version of the law, though: The Kentucky House, under Democratic control, had championed the program. Last November, the House flipped to Republicans.

A different test of the free community college idea will come in Tennessee, where the first class of students under the state’s Promise program is set to graduate this year. Stephen Parker, a legislative director at the National Governors Association, says peers in other states will look at what happens with that first class. “The graduation rate will be incredibly important to watch,” he says, “as well as how those students fare on the job market.”

—J.B. Wogan