Illinois voters have endured a lot from their state government. It hasn’t been just one recession or one administration that’s done the damage, either. It’s been nearly a generation of political upheaval and dysfunction at the state Capitol. “Springfield has not been working for them, and I think voters, residents of Illinois are frustrated and angry. They should be,” Rauner tells me after his Moline event. “Always unbalanced budgets. Not paying pensions. Not growing the economy and creating good-paying jobs. Massive corruption, cronyism and patronage. And four of my nine predecessors have gone to prison. It’s a broken system.”

Nearly everyone agrees with Rauner that the system is broken, but there’s no consensus about why the system is failing. Pick your favorite culprit -- legislators, unions, pensions -- and you may have a case. But the one thing that current and former elected officials, academics and Springfield insiders cite most is perhaps the most painfully obvious: “Illinois government did work,” says former Gov. Jim Edgar, a Republican who presided over what now looks to be the state’s heyday in the 1990s. “But then we had bad luck with a couple of governors.”

Illinois governors are powerful. They have many executive tools at their disposal that their counterparts in other states don’t possess. As chief executives, they have the biggest say on the state’s financial situation and the biggest platform to tend to the state’s economy. But over the last two decades, public confidence, financial stability and economic growth in Illinois have all suffered.

During that time, Illinois has had four governors: two Republicans and two Democrats. George Ryan came first, starting in 1999, and despite substantial achievements in Springfield, erased the public’s trust in state government with a corruption scandal that landed him in prison. Rod Blagojevich swept into power in the wake of Ryan’s scandal, promising reform and renewal, but exited in disgrace after an FBI arrest and subsequent impeachment trial, leaving a state woefully unprepared for the Great Recession. Illinoisans breathed a sigh of relief when Pat Quinn stepped in, but the relief died quickly, as a major tax increase failed to steady Illinois’ finances, and low-level patronage scandals undercut his reputation as a reformer. Rauner capitalized on Quinn’s unpopularity and defeated him in 2014. But Rauner saw his own standing collapse last year when rank-and-file GOP lawmakers abandoned his cause after a two-year budget standoff.

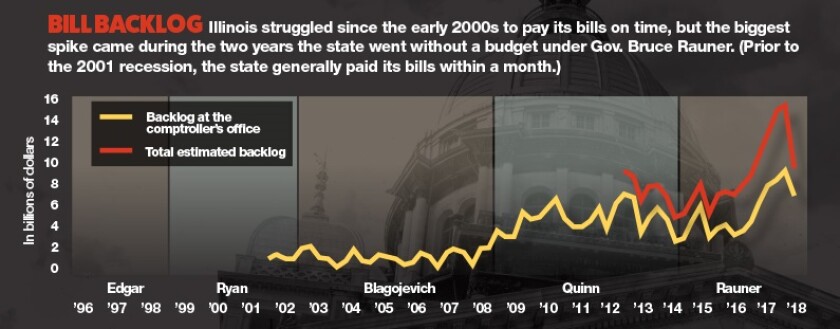

The cumulative effect is that the state’s credit rating teeters on the edge of junk bond status. Officials have only recently started dealing with a $16.7 billion backlog of unpaid day-to-day bills. Longer term, Illinois is $129 billion short of what it needs to pay its pension obligations. Only a tiny fraction of residents believes the state is heading in the right direction.

Getting Illinois back on track will require years of calm attention to rebuilding public trust, balancing budgets and practicing the neglected art of governing. “The governor has to be the fiscal leader. He has to be the one who worries about not going too far into debt,” Edgar says. “The legislature likes to spend money and it doesn’t want to raise taxes. They’ll blame you. That’s OK, though. That’s why you get the house, the car and the plane.” The fact is, he says, “good government is boring.”

But politics in Illinois has been anything but boring.

Twenty years ago, Illinois was humming along. Its median household income stood at nearly $64,000 in today’s dollars -- more than $6,300 above the national average and higher than it’s been at any time since 2000. Edgar handed his successor a surplus of more than $1 billion in state revenue. Bond ratings had been upgraded a handful of times during his tenure, a first in Illinois history. Lots of people grumbled at Edgar’s fiscal austerity, but he left office at the end of his eight-year tenure more popular than ever, with a 60 percent approval rating.

It was hard to see at the time, but the start of Illinois’ downward slide came with the election of George Ryan as governor in 1998. A Republican pharmacist from Kankakee, Ryan was an imposing figure with deep-set eyes, a gravelly voice and large hands that barely budged when you shook them. He rose through the ranks in Springfield as a legislator, House speaker, lieutenant governor and secretary of state. When Edgar decided to retire, Ryan was the logical choice for Republicans. His term as governor extended the GOP’s winning streak for that office to 26 years.

"Illinois government did work. But then we had bad luck with a couple of governors." – former Gov. Jim Edgar

But that’s not what Illinoisans remember him for. Instead, they associate him with a sprawling bribes-for-licenses scandal that dogged Ryan from his days as secretary of state. It sprang from an investigation over a fiery traffic crash in 1994 that killed five children because an Illinois trucker failed to heed warnings that his taillight was loose. The truck driver, it turned out, had bribed someone who worked for Ryan to get his Illinois commercial driver’s license. (In Illinois, the secretary of state administers driver’s license facilities.)

To advance his career, Ryan not only developed political skills that helped him cut deals on big-ticket issues but also relied on cozy relations with contractors and a de facto patronage army of workers at the secretary of state’s office. Corruption allegations followed Ryan to the governor’s office and clouded most of his term. His approval ratings plummeted from 50 percent in 1999 to 27 percent a year later. Ryan defiantly denied any wrongdoing, but his standing would never recover.

From his weakened position, Ryan had to guide the state through an unprecedented fiscal crisis after the 2001 terrorist attacks. When the books closed on his final budget, Illinois had posted back-to-back deficits of more than $1 billion. An early retirement package that Ryan pushed to trim the state’s payrolls proved far more popular than he or lawmakers anticipated -- 11,000 employees jumped at the chance, compared to the 7,400 that Ryan and lawmakers expected. That drove up fiscal pressure on the state’s already-stressed pension funds.

SOURCE: Illinois Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability

Nobody was surprised when Ryan was indicted on a variety of federal corruption charges nearly a year after he left office. He served six and a half years in prison and was released in 2013. But the scandal that tainted his administration would open the door to a successor who would not only land in prison, but would also become a national pariah.

Rod Blagojevich became instantly infamous when the FBI arrested the sitting Illinois governor in his running clothes in the morning darkness of Dec. 9, 2008. The same feds who had patiently stalked Ryan for years said they had no choice but to arrest Blagojevich after listening to seven weeks of wiretaps of his phones and office. Blagojevich, they claimed, was about to sell an appointment to the U.S. Senate seat vacated by the newly elected president from Illinois, Barack Obama.

Illinois lawmakers quickly impeached and removed Blagojevich. But the disgraced governor launched a media roadshow while he awaited trial. His cartoonish claims of innocence failed to keep him out of prison -- there were, after all, lots and lots of wiretaps -- but the spectacle undercut Illinois’ reputation just months after Obama won the White House.

Even before Blagojevich’s self-immolation, he had wreaked havoc and brought long-lasting damage to Illinois’ government. To make a clean break from the Ryan years, Blagojevich had brought in out-of-state advisers and political neophytes to run his administration. They quickly ran into a big problem: Illinois’ government still had not recovered from the 2001 recession, and there was precious little money to pay for ambitious programs.

So Blagojevich’s team came up with a brazen idea: a $10 billion pension bond sale. While the state might have conceivably saved money in the deal, in reality it was an elaborate way to skip $2.7 billion in otherwise required pension payments. Lawmakers went along with the idea anyway. The gimmick not only deprived the pension systems of needed cash, it also skewed the state’s budgets for two years. When the third year came, there was no money “built in” to the budget for pension payments. So Blagojevich and the Democratic-controlled legislature opted to take a “pension holiday” for another two years. That meant they’d pay only half of their expected contribution, shorting the system another $6.8 billion.

Even before Rod Blagojevich's self-immolation, he had wreaked havoc and brought long-lasting damage to Illinois' government. (AP)

Meanwhile, Blagojevich quickly made enemies with the leader of his own party in Springfield, House Speaker Michael J. Madigan. Shortly after Blagojevich’s reelection, the governor suggested switching from a sales tax to a gross receipts tax. Madigan, who opposed the idea, embarrassed the governor by quickly putting it up for consideration in the House, where it failed to get a single vote.

On top of that, federal prosecutors and local reporters started to look into Blagojevich’s fundraising tactics, especially because so many of the people Blagojevich appointed to state boards and commissions had contributed tens of thousands of dollars to the governor’s campaign.

Two months before his arrest, Blagojevich had few friends left, in Springfield or in the state as a whole. The Chicago Tribune reported in October 2008 that only 13 percent of Illinoisans viewed him favorably. FBI wiretaps showed that the feeling was mutual. “I [expletive] busted my ass and pissed people off and gave your grandmother a free [expletive] ride on a bus. OK? I gave your [expletive] baby a chance to have health care,” the governor vented, as he ticked off some of his legislative achievements. “And what do I get for that? Only 13 percent of you all out there think I’m doing a good job. So [expletive] all of you.”

Before Blagojevich’s removal, few people would have envisioned Pat Quinn as governor. For decades, the Democrat had been in and around state government, but mostly as a rabble rouser. In the early 1980s, he led a successful effort to reduce the size of the Illinois House by a third, but then he bounced from office to office. He won election for a single term as state treasurer, lost a bid to oust Ryan as secretary of state and then ran successfully for lieutenant governor on the same ticket as Blagojevich. (At the time, Illinois gubernatorial candidates did not pick their running mates.)

Once Quinn became governor, he did a lot of heavy lifting, especially on budget-related matters, that Blagojevich refused to do. But he had to do it in the throes of the Great Recession.

Months after assuming office, Quinn reported that the state would face an $11.6 billion shortfall over the next year and a half if lawmakers didn’t take drastic action. That came at a moment when the backlog of unpaid bills had risen to $8 billion. The legislature cut spending by $2 billion, gave Quinn the power to cut $1 billion more, relied on $1.8 billion in federal stimulus money and authorized $3.7 billion in short-term borrowing to make that year’s pension payment. It wasn’t enough, and the situation kept getting worse.

SOURCE: Illinois Office of the Comptroller

When Quinn ran for a full term in 2010, he campaigned on raising the state’s income tax by a percentage point to address persistent deficits. But within two months of his victory, rating agency threats of a downgrade to junk bond status and a projected deficit of $15 billion convinced Quinn that more was needed. So he persuaded outgoing lawmakers in a lame-duck session to raise the income tax by double the original proposed amount. Lawmakers hiked personal income tax rates from 3 percent to 5 percent, and raised corporate rates as well. The catch was that the new rates would last only four years before going back down.

But the new money did help the state catch up with some of its unpaid bills. By the end of Quinn’s term, the backlog was down to $6.6 billion.

Quinn also tried to take on the pension problem by reducing retirement benefits. In 2010, he signed a law that reduced pensions for most new state employees and teachers. But Quinn pressed for more, and in 2013, lawmakers agreed to a package that would have curbed benefits even for workers and retirees covered under the original pension scheme. Those changes, though, never took effect. In 2015, the state Supreme Court struck down the law for violating the Illinois Constitution, which has strong protections against diminishing retirement benefits for state employees.

"Pat Quinn is not the folksy, bumbling fool he'd like us to think he is." – Bruce Rauner, campaigning in 2014

When Quinn came up for reelection in 2014, his loudest critic was a wealthy businessman who won the Republican nomination to oppose him. “Pat Quinn is not the folksy, bumbling fool he’d like us to think he is,” Bruce Rauner said at the time. “He knows what he’s doing. He knows what he’s done.”

Once Pat Quinn became governor, he did a lot of heavy lifting, especially on budget-related matters. But he had to do it in the throes of the Great Recession. (AP)

Although Rauner had long mingled in political circles and once counted Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel as a friend, he was virtually unknown to most Illinoisans before his bid for governor. But the private equity investor soon became a household name, thanks to the $65.3 million he spent of his own money to boost his candidacy and a general election message that centered on his frugality and the need to “shake up Springfield.”

Once in office, though, Rauner set his sights on limiting the power of public employee unions and career politicians in the General Assembly. He called for far-reaching concessions that would have limited the power of both and demanded that they be met before he signed a full year’s budget. Illinois desperately needed a budget, because the temporary income tax hike that Quinn pushed through expired just before Rauner came into office, and there were no spending cuts to offset the lost revenue.

But rather than being cowed by the governor’s tactics, labor leaders and Democrats in the General Assembly dug in their heels. The standoff lasted nearly two years, during which time Illinois limped along without any clear spending plan. It was the longest span any state had ever gone without a budget.

Strangely, much of the government continued to function. Long-standing laws required Illinois to make pension contributions and bond payments even without a budget. Rauner cut a deal with lawmakers to keep money flowing to schools during the hiatus. And courts insisted that state employees be paid, and ordered the state to abide by consent decrees that mandated spending on certain social services.

But the impasse created all sorts of havoc in other places. It devastated nonprofit social service agencies that worked with the state but weren’t covered by court orders. Many of them had already reduced services and laid off staff during the recession. State-run universities also got no funding from Springfield during the budget crisis. All sorts of contractors, from the utility that provided power to the Capitol to dentists who treated state employees, were frozen out as well.

Meanwhile, the backlog of unpaid bills shot up again. Illinois was spending about the same amount it had spent when the income tax had been higher, but the state was no longer collecting enough money to sustain that spending. By last November, Illinois was $16.7 billion behind in its payments. Comptroller Susana Mendoza warned that Illinois was dangerously close to not having enough cash to meet court orders to pay for essential services, which meant Illinois could be held in contempt of court in several cases.

On Wall Street, bond rating agencies grew increasingly alarmed by the impasse. Two of the three downgraded Illinois to a step above junk bond status. If they had moved it any lower, institutional investors would no longer have been able to buy the state’s debt, because it would be considered too risky. No state had ever been in this situation.

SOURCE: Illinois Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability

As the collateral damage grew, so did pressure on lawmakers to end the crisis. In the Senate, President John Cullerton started negotiating with the Republican leader, Christine Radogno, to come up with a “grand bargain” that would combine some of Rauner’s business-minded proposals with a restoration of the income tax increase. The talks were so promising that the governor even counted on the revenue they would produce in his annual budget proposal. But as the deal moved closer to a vote, Rauner attached ever more demands and ultimately warned Republican senators not to support it.

So Democrats, who have a supermajority in the Senate, passed the budget they negotiated with Republicans, which included both the tax hike and $3.8 billion in spending cuts. But they did not pass changes to the worker’s compensation system or a local property tax freeze that Rauner wanted. “The governor got none of his so-called reforms,” Cullerton says. “He doesn’t know how to work or compromise.”

The Senate’s action shifted focus to the House, where Blagojevich’s old nemesis, Speaker Madigan, had emerged as Rauner’s whipping boy and most stubborn obstacle. Unlike in the Senate, though, Democrats on their own didn’t have enough votes to pass a budget and override Rauner’s expected veto. They needed a handful of Republicans to go along, too.

The impetus came from rank-and-file Republicans. Rep. David Harris was one of them. “What we did with the two-year budget stalemate was the most disgraceful thing the Illinois General Assembly has ever done,” he says. He met with a group of about 10 fellow Republicans -- many of them from downstate, which was “on fire” because of the impasse, he says -- to figure out what they wanted in the budget if they negotiated with Democrats. They wanted to know whether Democrats were serious about ending the standoff, or just wanted to use it to discredit the governor.

The House Democrats took them up on their offer to work together. Fifteen Republicans were among the 72 House members who supported the spending plan. When Rauner vetoed the measure, 10 of the GOP members joined in a successful move to override him. On July 6, 2017, after two years of costly stalemate and embarrassment, Illinois finally had a budget again.

The budget package allowed the state to borrow money to pay off its oldest bills, which due to penalties were accruing interest at a rate of 12 percent annually. Those bonds were also used to pay off Medicaid bills, because the state receives matching federal funds for those expenses. The governor describes the budget as a “massive loss for taxpayers in the state.” Was it worth fighting about? He thinks so. “It’s never in the best interest of the people of Illinois to compromise on raising taxes with no reforms,” he says. “That’s a disaster.”

For several years, Moody’s Analytics, which examines the state’s economy for the legislature, has warned that the uncertainty over Illinois’ financial situation “threatens to discourage firms from locating or remaining in the state.” It’s not that Illinois’ costs of doing business are particularly high, the economists note. Its taxes, labor and energy costs are in the middle of the pack for industrial Midwest states. What sets Illinois apart, they say, is the recent political tumult in Springfield. The state went more than two decades with stable income tax rates, but since 2011, it’s changed those rates three times, making long-term planning for businesses difficult. “The good news,” Moody’s added this year, “is that the state’s two-year budget logjam finally broke with the passage of a $36 billion spending package, easing some of the long-standing uncertainty in the outlook.”

On the budget standoff, Bruce Rauner says, "it's never in the best interest of the people of Illinois to compromise on raising taxes with no reforms." (AP)

There is another widely held theory to explain Illinois’ decades of mismanagement, and one that Rauner has had a lead role in promoting. That is the idea that Madigan, the powerful House speaker who has held the title for all but two years since 1983, is the real center of power in Springfield. Rauner and many of his fellow Republicans point their fingers at Madigan as the true source of trouble in state government.

There’s no question Madigan is a powerful figure. The speaker controls the legislative agenda in the House, and makes most of the important decisions behind closed doors, leaving lobbyists, members, the media and even governors to guess why certain bills die or suddenly come back to life. His pronouncements to the press are practically Delphic, and his public remarks rarely deviate from a very short script.

In addition to being speaker, Madigan is the chair of the state Democratic Party and a much-feared ward boss on the southwest side of Chicago. He has allies throughout government: former staffers who now have lucrative lobbying practices; neighborhood residents who got government jobs thanks to his clout; and judges and legislators he supported in tough election fights. On top of that, he is the partial owner of Chicago’s top law firm for property tax appeals, meaning that huge corporations come to him to try to knock off some of their tax bills for downtown skyscrapers.

Madigan has been entrenched in Illinois politics for so long that he’s had a hand in basically every major decision the state has made for decades. He went along with budgets that ran deficits, shorted the pension systems, underfunded schools, empowered unions and imposed regulations. “Madigan’s got an empire in the state of Illinois. He’s led the corruption. And he’s very powerful,” says Rauner, who, along with Republican groups that he largely funds, has hammered Madigan with similar messages on TV commercials for nearly three years now. There is no sign that they will let off anytime soon. Rauner says his Democratic opponent this coming November, J.B. Pritzker, is Madigan’s “hand-picked candidate.”

Rep. Barbara Flynn Currie, Madigan’s top lieutenant in the House, says Rauner’s constant talk of corruption has poisoned the atmosphere in Springfield, especially because business groups and the Chicago Tribune editorial board have also pounded away at the message. “You can disagree with someone’s policies without calling them corrupt,” she says. “The people who should be cheerleading for the state are spewing doom and gloom.”

There are a few big holes in the theory of Madigan as the root of all evil. The first is that the timing doesn’t work. Illinois’ troubles have come and gone and come again all while Madigan held the speaker’s gavel. They don’t seem to be tied to the presiding officer of the lower chamber, so much as the occupant of the executive suite on the second floor of the Capitol. The second problem is that it doesn’t explain why Republicans cheered Madigan as he led the opposition to Blagojevich but denounced him when he used similar tactics against Rauner.

Rauner and many of his fellow Republicans point their fingers at House speaker Michael Madigan as the true source of trouble in state government. (AP)

But maybe the biggest shortcoming of anti-Madiganism is that it imbues the speaker with more clout than he actually wields. Madigan has stayed in power all these years because he can read the changing political dynamics. He has crossed traditional allies such as teachers unions, trial lawyers and Chicago mayors when the politics demanded it. But even he has misjudged the climate from time to time. He recently faced threats to his position, at least as head of the Democratic Party, because of harassment allegations in his political operation. He himself was not implicated.

Both Democrats and Republicans have benefited from inflating Madigan’s stature. His Democratic allies gain the advantage of a friend whom no one wants to cross. Republicans get an enemy who is easy to vilify, encouraging them to rally voters to support GOP candidates.

As governor in the 1990s, Edgar, a Republican, often ran afoul of Madigan. He jokes that, when he had to undergo quadruple bypass surgery in office, he blamed one of the bypasses on stress caused by Madigan. But it’s easy to go too far, he says. “The media give too much credit to Madigan. He’s very smart. He was the smartest guy in Springfield when I was there. You have to treat him with respect. But still, the governor is the important thing. Even a weak governor like Blagojevich is stronger than the speaker.”

Does Rauner agree? “No,” he says, emphatically. “The governor is strong, and I’ve done major things. And I’ve beat him.” But, Rauner adds, “those victories are difficult and not often enough. He’s got too much concentrated power.”

"[House Speaker Michael] Madigan's got an empire in the state of Illinois. He's led the corruption. And he's very powerful." – Gov. Bruce Rauner

But as Rauner addresses the workers in Moline, he is trying to reassure them. He talks up the state’s educated workforce, its vital infrastructure, its manufacturing prowess. “We have every advantage in Illinois,” he says.

One can see signs of economic vitality while driving through the hills of northern Illinois. Huge new wind turbines and mirror-sided grain elevators rise in the distance. Farther east, construction crews erect towering corporate headquarters and condo towers that will join Chicago’s iconic skyline.

David Harris, one of the GOP lawmakers who opposed Rauner on the budget vote, makes a point to stand up every day in the Illinois House to say something good about the state. In these strange times, it’s something of an act of political defiance. “There is a commitment on the part of public officials to address our problems,” he tells me. “Don’t write us off simply because of some of the bad things you hear. There’s an awful lot that Illinois has to offer.”