Almost immediately, the announcement created buzz among members of the broader infrastructure community nationwide, who were optimistic that the Chicago plan—while fuzzy on specifics—could prove to be one worth emulating, especially given the stalemates that have prevented Washington from meeting local infrastructure demands in recent years. “Sometimes if you want something done right, you’ve got to do it yourself,” Robert Puentes, an infrastructure expert with the Brookings Institution, wrote in The New Republic the day of the announcement.

The reaction in Emanuel’s hometown wasn’t as enthusiastic. The next-day headline in the Chicago Tribune called the details of the plan “sketchy” and highlighted the millions of dollars in campaign contributions that people from the financial sector—the very industry that could profit from the experiment—had given to the mayor.

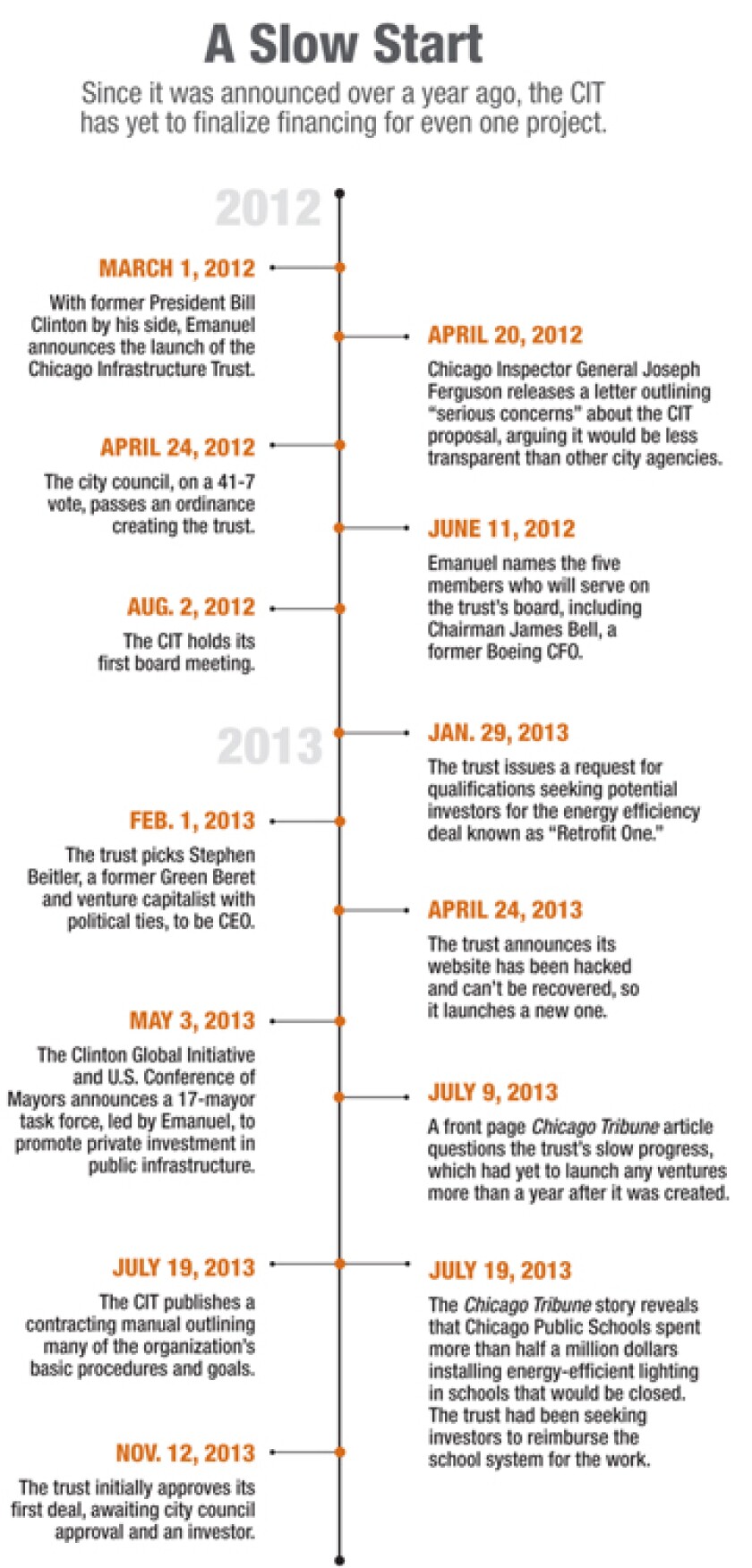

Just weeks after Emanuel made his proposal, the city council put it into law, as city leaders stressed the importance of not wasting time in addressing the Windy City’s needs. Over the ensuing months, Emanuel touted the concept to just about every major media outlet in the country. Eventually, the excitement about the plan died down. Today it’s been more than a year and a half since the trust was created, and Emanuel has little to show for the program that some speculated would be his crowning achievement. The trust only last month approved its first deal. With so few tangible accomplishments so far, that raises a crucial question: Is Chicago’s program really one worth replicating?

It’s a question that matters, since the trust’s advocates have made it clear that—despite its lack of a record at this point—they want to see versions of the Chicago program spring up in cities nationwide. “What we’re trying to do is to get other cities to do the same thing,” Clinton said during an appearance on MSNBC this summer. “Every mayor in the United States has an opportunity to do something without the financial support of the federal or state capitals,” Emanuel added.

In May, the Clinton Global Initiative announced that it had teamed up with the U.S. Conference of Mayors to create a task force that will address the infrastructure issues facing cities. Seventeen big-city mayors serve on the task force—Emanuel is chair—and it will specifically explore ways to utilize urban infrastructure banks and entice private capital to invest in public infrastructure. “If Chicago can point the way for other cities to attract new forms of financing, it will have done a great service,” Peter Orszag, a Citigroup executive and former White House official, who’s advising the task force, wrote in a Bloomberg piece earlier this year. Today, it seems that whenever the question of how to pay for infrastructure is raised, Chicago’s program is viewed as a solution—despite its glacially slow start. “I don’t see anything that would constrain this from being expanded to other cities, big and small,” says Martin Luby, a municipal finance professor at Chicago’s DePaul University. “It all comes down to whether there’s real investor interest in this.”

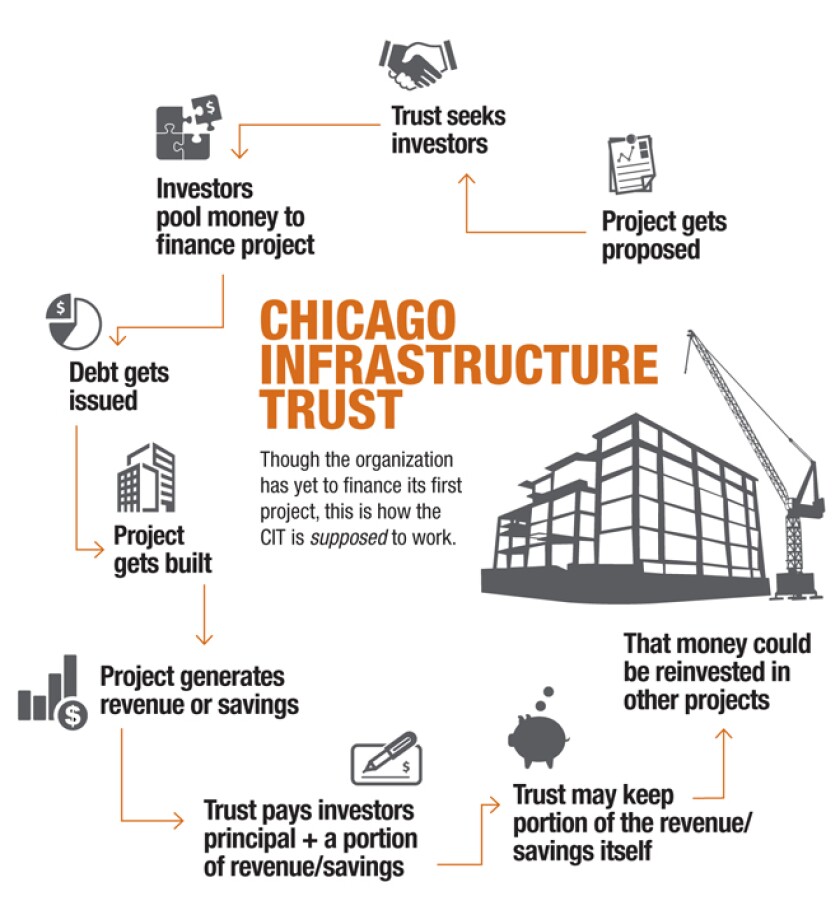

The trust is essentially a venue for the city to develop public-private partnerships (P3s). According to trust documents and Emanuel himself, it’s specifically designed to complete projects that the city couldn’t finance using traditional methods like municipal bonds. Typically, when local governments want to pay for infrastructure, it’s a straightforward process. Companies submit their best price for building a project, and the city issues low-interest, long-term municipal bonds to pay the winning bidder. With P3s, the private sector puts equity into a project and expects a direct return on its investment. Generally that’s a more expensive way for cities to borrow money. But Chicago has become more open to creative forms of financing, given recent dings to its credit rating.

Damon Silvers, a nonvoting member of the Chicago Infrastructure Trust’s advisory board, says it doesn’t usually make economic sense for governments to get equity financing from private capital instead of the municipal bond market. But, he says, in some cases the structure of the trust can provide much-needed flexibility. Advocates for the CIT say it holds promise for three key reasons. First, it could help shift risk from the city to the private sector for less conventional projects that might be unproven. For example, the trust's first deal, tentatively approved last month, involves spending $25 million on upgrades to city buildings designed to reduce the city's energy costs over time. Investors would pay for the retrofits up front, and in return, they’d get to keep a portion of those savings. But if the savings don’t materialize, the investors would ostensibly take the hit, not the city.

The second reason, supporters say, is that the private sector has a better track record than the public sector at maintaining assets over the course of their lifetime. That’s because when times get tough, maintenance budgets are often the first thing cities scrap to plug budget holes. But if investors have a stake in the long-term life of a piece of infrastructure, that would be less likely to happen. Municipal bond holders generally don’t worry about the success of a project as much as a city’s ability to repay a loan, says Michael Pagano, dean of the College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois at Chicago. But because investors in CIT projects would only earn a return from the projects in which they’ve directly invested, then they’d have a stake in facilitating successful ones.

Third, and perhaps most crucially, supporters of the plan say the city doesn’t have the borrowing capacity to rely on municipal bonds alone, given the vast amount of infrastructure work facing Chicago and the city’s sinking credit. In July, Moody’s Investors Service downgraded the city’s credit rating, citing its soaring pension costs, rising public safety demands and its unwillingness to raise taxes. The downgrade took the city’s general obligation bond debt down three notches to “A3,” and Moody’s also gave Chicago a negative outlook. In 2015, the city faces a $1.1 billion pension bill. “We don’t have enough resources to go around,” says Lois Scott, the city’s chief financial officer. “We just don’t. Instead of complaining about the problem, we decided to do something.” The trust may also give Chicago a way to take on debt while keeping the obligations off its balance sheet—a common reason governments pursue such deals. CIT managers say they’re working to ensure that’s exactly the case with the retrofit project, though city officials say off-balance sheet debt wasn’t their primary motivator for creating the trust.

Despite the early promise, the CIT still hasn’t finalized financing on even one project. And though it was pitched with great urgency in spring 2012, the CIT didn’t get an executive director until February of this year. Moreover, the trust issued its first request for qualifications for the energy retrofit back in January. So even if the deal is completely finalized this month, it will have taken almost all of 2013, at a minimum, to finalize that first deal.

That project, dubbed Retrofit One, would have raised $115 million to pay for energy-efficiency retrofits at more than 100 city buildings, including lighting improvements in city schools and the conversion of a pump station from steam to electricity. But the work in the schools had already been completed. That development undermined the core argument that was made last year for the trust—that it will build things that otherwise would go unbuilt. (In another embarrassing hiccup, the Chicago Public Schools announced dozens of school closures earlier this year; the Chicago Tribune revealed that some of those buildings were among the ones that had already been outfitted with thousands of dollars worth of low-energy lighting that the trust was planning to finance.) Under a plan announced last month, the trust approved a drastically pared down version of the deal that would raise $25 million for improvements at 75 city facilities and would not include schools or the pump station. The city council must still approve the plan, and the trust must still select an investor.

Those involved with the trust say hurdles and hiccups are to be expected, given that they’re creating an organization from scratch. “You really can’t just snap your finger and say, ‘This is what happens,’” says Steve Beitler, the trust’s CEO. Much of his time has been spent doing basic things like establishing a website and getting office space. “I get on phone calls where sometimes there are 20 lawyers on the call.” He says many of the legal questions the trust is sorting through right now won’t have to be asked again for future transactions, which will make deals move more quickly. “The trust is, in every respect, a startup,” he says.

Those obstacles aside, it’s not clear whether Chicago’s infrastructure bank is anything other than a high-profile way for the city to signal its openness to P3s, which have long been popular abroad and have gained increased use and attention over the last 15 years in places like Colorado, Texas and Virginia. Beitler, a former Green Beret who later founded a venture capitalist firm, is the first to admit what the trust is doing isn’t entirely original. He says the CIT is trying to learn lessons from places like Australia, British Columbia, the United Kingdom and Virginia about how best to run organizations specifically tasked with arranging P3s. “Basically, I think, the amount of publicity is not warranted,” he says, “and there are such great organizations that don’t get anywhere near the publicity that is warranted for them.”

But Beitler says the trust is unique in that it could pursue projects beyond those related to transportation, including utilities, energy or telecommunications. Beitler’s especially excited about figuring out how the city can make money off underutilized property. The thinking is that Chicago may have city-owned buildings in areas where it would make more economic sense to have a different type of development on the same footprint. If the city could relocate its facilities elsewhere, it might be able to generate revenue based on higher property taxes and other fees a private developer could pay for the spot. The details haven’t been fleshed out, but the trust already has an early version of a database containing all of Chicago’s publicly owned property that it’s analyzing.

Still, the undertaking has its critics. Emily Miller, policy and government affairs coordinator for the Chicago-based Better Government Association, was an early skeptic of the proposal. She says that while the energy retrofit seems like a smart idea, the trust doesn’t seem to have an overarching goal and looks to be taking a scattershot, uncoordinated approach to the types of projects it’s pursuing. “I don’t know what the vision is,” says Miller. “These pieces of ingenuity only work if it’s part of a bigger picture.”

And while the Chicago City Council overwhelming approved the legislation creating the trust, several aldermen remain highly critical of the program because they say it was crafted with too little transparency and too few protections for taxpayers. Moreover, there’s been some speculation that Emanuel could be considering a 2016 presidential run, and the creation of the trust may have been a clever way for him to position himself as a national expert on infrastructure. (Emanuel, for his part, has repeatedly denied presidential aspirations.) “Rahm has that incredible PR machine ... making sure there’s so much positive stuff out there that it puts everything into a good light, and you don’t see through some of the issues that are out there,” says Alderman Scott Waguespack.

There are also skeptics who don’t buy the economic argument for the trust. Julie Roin, a University of Chicago law professor, says it’s unclear why, exactly, the trust needs to tap private capital when the municipal bond market has historically worked well for cities. She says borrowing money from private investors is still borrowing; whether bondholders get paid back with city tax dollars or some other revenue stream tied to a public asset, at the end of the day, it’s still public dollars being spent. “I think there’s no difference between the two, other than the political optics,” Roin says. Alderman John Arena, who voted against the trust, agrees. He says he wasn’t impressed with a briefing that Beitler gave the council. “None of the examples they gave us were things that could not be bonded on the open market as it existed,” Arena says. “It really felt like it wasn’t fully cooked in terms of a concept.”

There’s also the question of what types of projects can really be financed by the endeavor. During the announcement of the trust, Clinton said “there’s no limit to what you can do because of this device.” That, however, runs counter to what both finance experts and officials involved with the trust say. In all likelihood, it will only be able to facilitate projects that offer up some sort of easily identifiable revenue stream to pay investors. Joseph Schwieterman, a public policy professor at DePaul University, says those opportunities may not be easy to find. “That’s where we’re all scratching our heads, to see where these revenue streams are. It’s not clear where you have unexploited revenue opportunities.”

Critics also like to point out Chicago’s less-than-sterling reputation when it comes to P3s, best illustrated by its infamous parking meter debacle. Five years ago, then-Mayor Richard M. Daley locked the city into a deal in which Chicago got $1 billion from private investors to help balance its budget. In exchange, it gave up 75 years’ worth of meter revenue. The city’s inspector general found that the city leased the system for 46 percent less than what it was worth; in simple terms, it got ripped off to the tune of nearly $1 billion. The deal is still a subject of anger in Chicago, and officials say the memory of that deal is always in the back of their minds as they do their work.

MarySue Barrett, a nonvoting member of the trust’s advisory board, says the board is largely focused on doing everything it can do to avoid another catastrophe like that. “We can’t afford to have a project that’s not a slam dunk,” Barrett says. “It’s not just about proving the detractors wrong,” she continues. “There’s a responsibility and an accountability all of us working on the trust feel. We know the world is watching.”