This year was no different, even though lawmakers came tantalizingly close to a road improvement package. A week or so after they failed to pass a fix-up plan, Gov. Phil Bryant announced that the state Transportation Department would immediately shut down 83 locally owned bridges. Federal inspectors had found that the bridges -- most of which were built with timber parts and located in rural areas -- were deficient and unsafe for vehicular traffic. Since then, more bridges have been added to the list. All told, some 500 across the state are out of service.

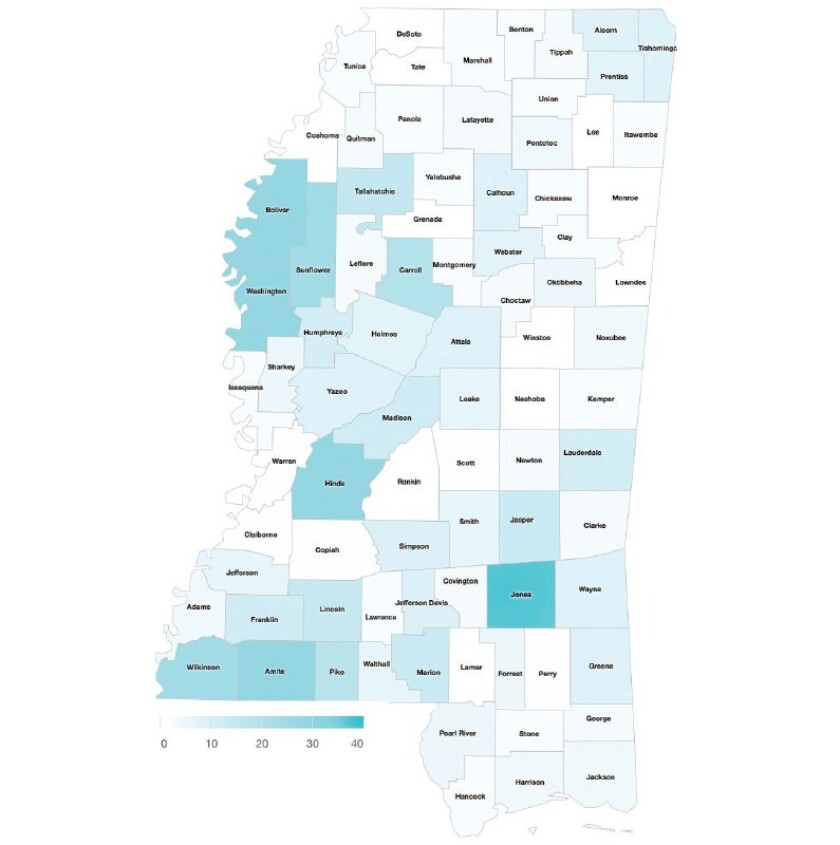

“It is probably the No. 1 problem the citizens are talking about today,” says state Sen. Willie Simmons, a Democrat who chairs the chamber’s Highways and Transportation Committee. Two of the counties in Simmons’ Mississippi Delta district shut down more than 30 bridges each. Those closures can reroute residents on 40- to 50-mile detours, and they can prevent firefighters and paramedics from getting to residents quickly. “Everybody agrees that we have a crisis, and it needs to be addressed,” Simmons says. “The problem is, we need to find the ways and means to pay for it.”

Many states face tough questions about how to improve their roads, particularly in rural areas. These dilemmas are the driving force behind President Trump’s call for rural infrastructure improvements. But even the president’s plan demands increased state and local funding, and Mississippi, more than most places, has struggled to come up with the money to keep its roads and bridges in usable shape. Since 2012, for instance, 30 states have boosted their transportation spending, most by raising their gas tax. Under the eagle-topped dome in Jackson, however, that idea has been a nonstarter. The last time the state raised its gas tax rates was in 1987; only Alaska and Oklahoma have gone longer without touching their fuel tax rates.

Mississippi’s 1987 gas tax hike is the stuff of local legend. It started when Gov. William Allain tried to pressure lawmakers into eliminating the state’s elected transportation commissioners. Allain had reshaped Mississippi government to consolidate power within the executive branch and didn’t want another group of officials calling the shots at the highway department. But one of the commissioners rallied the business community to oppose Allain’s maneuver and, in the process, came up with a plan to build four-lane highways around the state. At the time, only interstates and a handful of highways had four lanes, which made it difficult to haul freight to far corners of the state. The group’s goal quickly became to make sure every Mississippi resident lived within 30 miles or a 30-minute drive of a four-lane highway. They promised it could be done with just a nickel hike in the gasoline tax.

Several powerful lawmakers joined the cause and were able to scrape together enough votes in the House to send the legislation to the governor’s desk. Allain vetoed it. The bill’s backers had to scramble to find enough votes to override him. In the end, both the House and Senate narrowly rejected the veto and the measure became law. The state gas tax went up to 18.4 cents a gallon, identical to the federal rate set in 1993. Through 2002, the fuel tax hike brought in $2.6 billion, which was used to build 1,088 miles of four-lane highways. Those highways, Mississippi officials say, helped lure manufacturers like Nissan and Toyota to the state, because they made it easier to ship goods and equipment through the region.

But the law had some features that, over time, transportation advocates have regretted. First is that the per-gallon tax was fixed, and did not automatically adjust for inflation. Meanwhile, vehicles have become far more fuel-efficient, which means motorists don’t need to buy as much gas. So by 2015, Mississippi only collected 1.6 percent more in gas tax revenue than it did after the 1987 law passed. But inflation had grown by 108 percent, and construction costs by 217 percent.

Christian Gardner works as an engineer for three counties, each of which has 25 or more closed bridges.

The second, and perhaps most glaring, shortcoming was that, while the 1987 law guaranteed a source to pay for new construction, it did not set aside any money for maintenance once the new roads were built. “There has been no significant change in state revenue for roads and bridges since 1987,” says Melinda McGrath, the executive director of the Mississippi Department of Transportation. “This has caused many Mississippi highways to crumble past the point of repair, and they now require complete rehabilitation.”

The department has told lawmakers that it needs a permanent increase of at least $400 million more a year to bring the state’s road network into good shape. In order to focus on maintenance and repairs, the agency has had to put off most road expansion projects that would handle population growth or support economic development.

Transportation advocates within the government have looked back at the 1987 victory and tried to use some of the same organizing tactics. The legislature’s transportation committees have worked to rally the public by traveling around the state, either to hold public hearings or see the operations of the state transportation department firsthand.

Outside allies have also tried to help. Two years ago, the Mississippi Economic Council, the state’s biggest business group, lobbied hard to persuade legislators to increase gas taxes to pay for better roads. Mike Pepper, the executive director of the Mississippi Road Builders Association, says raising the gas tax is the logical way to fix the problem. When he talks to his colleagues in other states, they tell him they have “all gone through the same thing of trying to find a way to do this without raising the gas tax. They beat their heads against the wall and gnash their teeth, but they always come back to the gas tax. It’s the fairest, most equitable way to pay for transportation.”

That’s been the story in conservative states as well as liberal ones, notes Pepper. “There’s nothing conservative in ignoring the state’s investment in infrastructure,” he says. “If shingles were blowing off the roof of your house, you would put new shingles on. You wouldn’t wait until the deck is rotten before you replaced them. Well, the shingles are off.”

As of this spring, more than 540 bridges in Mississippi have been closed. In some counties, as many as 30 bridges were shut down, rerouting residents on 40- to 50-mile detours.

Those arguments, and the lobbying efforts behind them, have pressured lawmakers and the public to talk about the condition of the state’s roads. But no new funding has come as a result. The 1987 playbook isn’t working for a variety of reasons, starting with the overhaul of the political landscape in Mississippi over the last three decades. In 1987, a Democratic legislature overrode a Democratic governor to pass the law. But Republicans took complete control of Mississippi state government in 2011.

Today, anti-tax groups like Americans for Prosperity are very influential in Mississippi. That organization, for example, spent at least $10,000 last year on direct mail and digital marketing to praise Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves, who presides over the Senate, for thwarting efforts to raise the state’s gas tax or to use tax proceeds from online purchases to fund transportation. Eleven of the state’s 52 senators attended an Americans for Prosperity event last year where several promised not to raise the gas tax.

Simmons, the Senate transportation chair, says he couldn’t find 15 senators to support a gas tax, a lottery or higher hotel taxes to increase road funding. In the House, fewer than 40 of the chamber’s 122 members backed similar proposals.

Russ Latino, the state director of Americans for Prosperity in Mississippi, says lawmakers’ opposition to tax hikes reflects the conservative nature of the state. He points out that the leadership in the House, the Senate and the governor’s office all campaigned on being for lower taxes, smaller government and less regulation. “People are living up to what they promised voters,” he says. “Voters are overwhelmingly opposed to increasing the gas tax.”

While state lawmakers wrangle over potential funding sources, local governments -- particularly counties -- are bearing the brunt of the shortfalls. As in many states, the responsibilities for keeping up roads in Mississippi is split between the state and localities. The state Transportation Department controls interstates and highways. A separate state agency helps localities maintain “state aid” roads and bridges. The state also gives some gas tax money directly to counties. While the bulk of traffic is on state-owned roads, most of the road miles are owned by counties. They are responsible for 52,000 miles of roads with nearly 10,000 bridges.

Christian Gardner, who works as a county engineer for three counties, says he’s watched the slow deterioration of roads. When Gardner got out of college in the early 1990s, the new road bill had been passed, and counties could replace bridges, do maintenance and still have money left over for new construction. By the early 2000s, however, new construction “disappeared,” but counties could at least maintain what they had. “Fast forward to 2010,” he says, “and it’s clear that most counties are not going to do any improvements.” They’ve fallen behind on bridge maintenance and there’s been no new construction. In fact, nearly half of county roads are in poor or very poor condition. Today, Gardner says, “I walk into my board meetings and say, ‘We’re going backwards.’”

How did that happen? Well, for example, in 1987 the cost of resealing 47 miles of road was $981,000. Nowadays, because of inflation, the cost has more than tripled. But transportation money for the counties has remained relatively flat, and counties don’t have many options to make up the difference. They’re basically limited to property taxes since counties can’t impose sales taxes or gas taxes. And property values through most of the state have not gone up, which makes it difficult to hike the tax. Even if they could justify an increase, officials at both the state and local level in Mississippi tend to be tax averse.

Gardner, with fellow engineer Ron Cassada, says that with so little money available, counties have to choose between maintaining roads or replacing failing bridges.

For most roads in poor condition, it will take about $50,000 to $70,000 per mile to bring them back into good shape, says Gardner. But the cost is higher if counties fail to do regular maintenance. As Gardner explains, if cracks in the pavement are not sealed and water gets into them, roads start to break up. “It gets to a point where you can’t chip seal it anymore,” he says. “You have to do a road bed reclamation. The actual pavement needs reconstructing. Now that’s about $500,000 a mile.”

With so little money available, county supervisors have to weigh whether it’s better to properly maintain a well-used county road or to replace a failing bridge that few people use, which could cost at least $400,000. “Do I let the few be inconvenienced for the majority, or do I let the road go down and replace the bridges?” Gardner says. “It’s not quite as simple as spending every penny you have on bridges. If we did that, we won’t have a paved road left in the county.”

Bryant’s decision this spring to shut down bridges jolted the Mississippi political establishment, but it was in the works for more than a year. In fact, Simmons, the head of the Senate transportation committee, warned his colleagues about the heightened federal scrutiny and the likelihood of closures as the chamber was wrapping up its spring session a year ago.

The conflict with the Federal Highway Administration started with routine spot checks of about a dozen rural Mississippi bridges in early 2017. FHWA officials were concerned with the state of the bridges and recommended that several be shut down. The federal government doesn’t have the authority to close bridges on its own, but it can withhold federal transportation money if states don’t keep their road systems in good repair. Bryant’s emergency declaration applied to a handful of counties that refused to shut down bridges that didn’t meet federal standards; he ordered the state to close the bridges that counties wouldn’t on their own. (Two counties sued Bryant in May, arguing that he overstepped his authority by shutting down county bridges.)

Simpson County, southeast of Jackson, was one of the first places the federal inspectors went. No one knew they were coming, says Rhuel Dickinson, the county administrator. The sheriff’s office called Dickinson asking what they should do about people who had parked an unmarked van on the road and were climbing around a bridge. “I kept them from getting arrested,” Dickinson says.

The county closed 18 bridges after those inspections. Most of them were old and had timber components. They had been checked every other year by the county’s inspectors, who noted the same defects that the federal inspectors highlighted. But the feds seemed to use more sophisticated methods, such as drilling through wood pilings rather than just sounding them with their hammers. Where county engineers might recommend a lower weight limit for a bridge and order repairs, the federal engineers would push to close it completely. “I’m not saying that’s wrong, but that’s not how our local engineers have been doing it for years,” Dickinson says.

Mississippi's crumbling roads and bridges are "probably the No.1 problem the citizens are talking about today," says state Sen. Willie Simmons. "The problem is, we need to find the ways and means to pay for it."

The new inspections, though, come with their own costs, in both money and opportunity. Simpson County had to spend $20,000 to buy barricades, signs and reflective barrels to shut down its bridges -- it only owned enough equipment to close three at a time. By the time all of the closed bridges are reopened, the county will likely spend $150,000 to $200,000 for repairs. Dickinson says it will be borrowing from next year’s road budget to make the payments. Meanwhile, a bridge project that was ready to go is now on hold, because the county had to pay for the repairs and inspections instead.

Connie Rockco, a Harrison County supervisor, says the lack of road money is also preventing Gulf Coast communities like Biloxi and Gulfport, which she represents, from building new infrastructure to accommodate population growth and to provide more hurricane evacuation routes. That’s obviously a major concern for an area that was devastated by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. But bigger cities like hers never benefited much from the 1987 highway bill since they were already served by major highways.

Rockco toured the state in a “road show” last year as the head of the Mississippi Association of Supervisors, trying to drum up support for a statewide road funding package. Engineers talked with legislators and county officials about road conditions. The supervisors pointed out that neighboring Tennessee had just raised its gas tax rates in order to fund projects that would promote economic development. “We tried to make it more palatable to the legislature, but they just didn’t want to raise taxes,” Rockco says. “We’re going to ultimately have to raise taxes, because they won’t.”

Ironically, the biggest issue that lawmakers could not resolve this session was whether local governments should have to put up more of their own money in order to get more help from the state. Early this year, the Mississippi House unanimously passed a bill to dedicate $108 million to roads, which would come from the state’s use tax (basically a sales tax that online retailers voluntarily collect and give to the state). The Senate came back with a much more sweeping $1 billion plan that would have used some of the state’s rainy day fund to pay for road improvements. The package would have included issuing bonds and setting new fees on electric and hybrid vehicles. But it also would have required cities and localities to chip in for projects in their jurisdictions.

Eventually, House and Senate negotiators met to try to work out their differences. They got 85 percent of the way there, says Sen. Joey Fillingane, a Republican who leads the finance committee, but they couldn’t agree on whether localities should pay more to get a bump in state funding. The House insisted that cities didn’t have the money to spend more on roads. Senate negotiators disagreed. “We’re supposed to be good stewards of state resources, and we’re not doing that by allowing the state to pay 100 percent of those projects,” says Fillingane. “Either you make infrastructure a priority or you don’t.”

In some ways, the Senate’s proposal mirrors the infrastructure push by the Trump administration in Washington. Just like President Trump, state senators want other levels of government -- in this case, cities and counties -- to provide a match. The troubled bridges are on county roads, says Fillingane. “They’re not the state’s responsibility, but we do try to give them state funds when we can afford it. It really comes down to the counties.”

Simmons, the Democrat who serves with Fillingane in the Senate, agrees that localities ought to pony up more to improve roads. But he says any of the ideas bandied about in the legislature this year “would simply be a start.” Even the Senate proposal would only raise a quarter of what is needed to bring Mississippi’s roads back into good shape. Still, after 30 years of waiting, a new start would be something.