Taking cars off streets yields a number of benefits for cities, including helping to attract young people, limiting pollution and facilitating safer roadways for both drivers and pedestrians, says Norman Garrick, who studies urban planning at the University of Connecticut. That’s part of the reason, he says, “cities are really doubling down and trying to reduce use of cars.”

By and large, though, most Americans don’t appear ready to ditch their cars just yet. Nationwide, about 9 percent of U.S. households didn’t have access to a car in 2013, according to Census data analyzed by Governing -- a figure that hasn’t changed much in recent years.

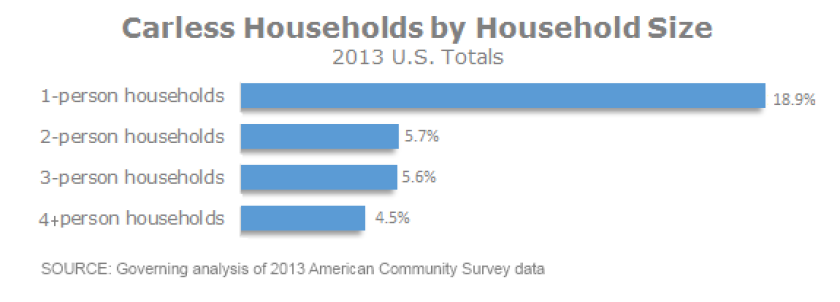

Demographics further illustrate how car-centric cities truly are. Census estimates suggest 19 percent of one-person households were carless in 2013, compared to less than 6 percent of larger households. Research has shown that younger couples and families rely somewhat less on their vehicles. It’s hard to say, though, the extent to which Millennials’ driving habits will depart from previous generations and whether they’re driving less because of lifestyle preferences or because they can’t afford the costs of car ownership.

Cities that aren’t car-dependent remain rare, with only 14 of the 794 jurisdictions reviewed registering less than one vehicle per household. Not surprisingly, areas identified as having the fewest cars per household were, like Jersey City, predominantly found in the transit-rich New York metro area. There are only about 0.6 vehicles for every household in New York City -- the least of any city nationally. Boston, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., are also among the select few cities with less than one vehicle per household.

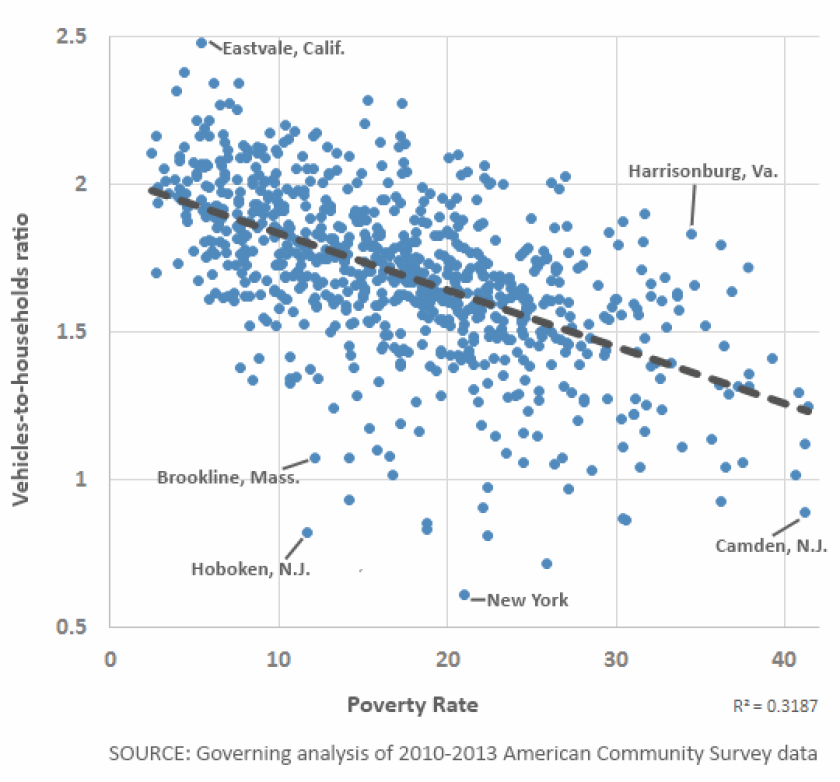

Cities with the fewest cars per household also include Camden, N.J., and Reading, Pa. -- two places with some of the nation’s highest poverty rates. More residents in these cities simply can’t afford to own vehicles. Poverty rates of cities reviewed correlated with lower numbers of vehicles per household. The following plot shows the relationship between the two measures with outliers identified:

Car-free cities are mostly confined to Europe. Both Paris and Madrid, for example, announced plans last year to ban or limit vehicles not driven by residents throughout central city districts. David Rouse, the American Planning Association’s research director, says it’s unlikely that most U.S. cities will become car-free anytime soon. It's the more densely populated cities that are beefing up transit systems to run more frequently, he says, that are in the best position to make progress.

Policies that push people to drive less or give up cars typically fall into one of two categories: those that discourage residents from driving and those providing better alternate modes of transportation. UConn’s Garrick says the most successful cities do both, akin to a carrot-and-stick approach. One of the more common strategies employed in Jersey City and elsewhere involves revising minimum parking requirements for developers. Campaigns encouraging motorists to go “car free” have also started up in places like Arlington County, Va., and San Luis Obispo County, Calif.

For some, the decision of whether to drive comes down to parking costs and availability. Garrick’s research in Hartford, for instance, found 71 percent of employees drove alone to work for an insurance company that charged for parking. Rates for other downtown Hartford employers offering free parking were between 83 and 95 percent. Car and bike shares, if they continue to expand, could factor into more commuters’ decisions as well.

Scott Polikov, president of Gateway Planning and a board member of the Congress for the New Urbanism, sees a few traits shared by regions that have started to shift away from a car-oriented culture. Metropolitan planning organizations in these jurisdictions make mixed-use development and alternative forms of transportation a priority. Areas with more competition within the development community also fare better. “There has always been a demand for reduced car trips,” Polikov says, “but our development patterns haven’t made it possible.”

Ultimately, despite growing appeals to take cars off roadways, there just isn’t a viable alternative yet to getting behind the wheel in most places. “If you ask people to take an extra two hours to take a bus or walk a mile,” Polikov says, “they’re typically not going to do it.”

Car Ownership in U.S. Cities Map

Vehicle ownership varies greatly throughout different regions of the country. In the many jurisdictions in the densely-populated New York metro area, there is less than one vehicle per every household. By contrast, there are more than two available vehicles per every household in other cities, mostly in California and Texas.(Click to open interactive map in new window)

carless-cities-map2.png

Review other Census data on transportation and commuting topics.