The attempt to measure quality in health care isn’t new. It’s a decades-old phenomenon, driven by the demands of the private sector as well as Medicaid and Medicare. But widespread fears about escalating health-care costs have given the movement an adrenalin-laced booster shot.

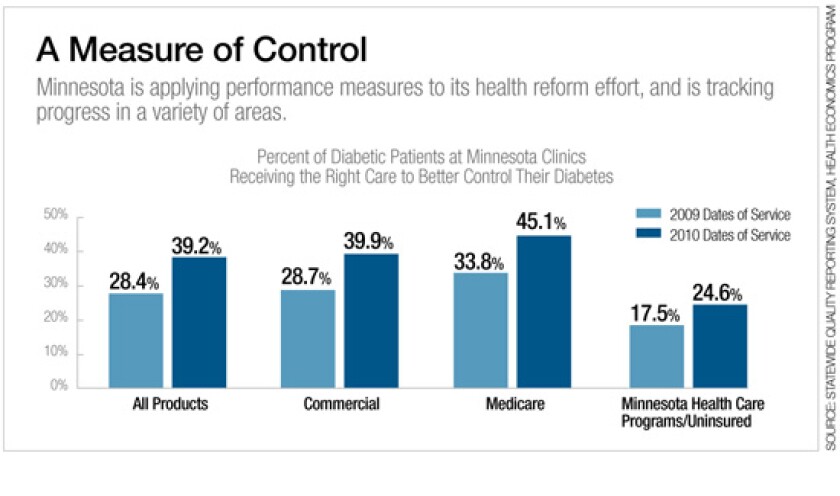

In Minnesota, for example, a plan is in the works to tie the public reporting of health quality measures to payment reform, with hospital-based physician clinics compared on their relative performance ratings in quality and costs. Reimbursement -- and consumer cost-sharing -- will be based on which categories physicians are in. A clinic with high performance and low cost will be reimbursed at a higher level -- and cost consumers less -- than one with lower performance and higher costs.

The integration of both quality and expense is critical. According to a recent study from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), when consumers only know how much a particular medical intervention costs, they tend to pick the higher-priced one on the false belief that it must be better. This is much like those old Consumer Reports ads in which customers, when they knew nothing about a vacuum’s ability to suck up dust, picked the higher-priced of two appliances. Consumer Reports was supposed to fill that information hole, so people could save money and still have super-clean floors. This is just the way quality measures can benefit the health-care arena.

Measures can sometimes be used effectively to help specific physicians improve outcomes. Jack Meyer, a professor with the University of Maryland, describes how the chief of surgery in one hospital worked with a heart surgeon to help him see that his bypass operations took longer than those performed by other doctors in the hospital. This presented a potential danger to patients. “The surgeon didn’t know he was out of line,” says Meyer. It also mattered that the information was delivered by the appropriate party. “If the CFO had come in and gotten in the face of the surgeon,” Meyer says, “there would have been a blowup. But it’s different if the chief of surgery comes in and says, ‘Did you know you’re an outlier? Let’s see if we can work together to improve.’”

A key difference between performance measures developed for health care and for other government topics is their consistency from place to place. These shared measures come from the work of the National Quality Forum (NQF), which was set up about 10 years ago as a private standard-setting body. The forum doesn’t create measures, but it carefully researches and vets them. About 85 percent of measures used in federal programs are NQF measures. In Minnesota, it’s estimated that about 75 percent of the measures used are NQF endorsed. “We need standardized measures so that you have apples-to-apples comparisons,” says Janet Corrigan, outgoing president and CEO of NQF. She says her organization’s work helps set priorities and reduces the data production and reporting burden on providers.

While there continues to be debate about how much quality measures can contribute to lower costs and improved performance, some of the impact of publicly reported health-care data has been striking. Reporting of central line-associated blood stream infections, for example, along with an aggressive campaign to improve practices, helped lead to a 63 percent drop in infection rates among U.S. intensive care patients between 2001 and 2009, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data. Similarly, a study in Wisconsin found that low-scoring health-care organizations that participated in reporting publicly on their performance improved measurably over time.

To be sure, there’s still room for improvement. Available outcomes -- like hospital readmission, mortality rates or patient satisfaction information -- only get part of the way. Follow-up information is wanting. If you’re looking at a total knee replacement, for example, it’s good to know what the patient’s experience with that knee is in a few years. Information on how someone is functioning after medical procedures or how health care affected their quality of life is still hard to come by.

What’s more, some providers continue to push back, complaining that the data often aren’t good enough, the comparisons may not be fair and that public reporting can compromise the doctor-patient relationship. “The challenge is that for every service provider group, you have to fight the battles that you thought you won years ago,” says Stefan Gildemeister, state health economist in the Minnesota Department of Health.

Then there are the consumers. A series of reports was prepared for AHRQ in 2010 on the many challenges of getting consumers to pay attention to health quality measures, which are often technical and complex. As one of the reports observed, relatively few consumers have “used comparative measures” to make health-care choices. “There’s a disconnect with people’s likely use of measures and what measures are there,” says Baruch College’s Sofaer, a co-author of that report.

That’s unfortunate. But even though there’s lots of work to be done, clear progress is being made on this front. What’s more, the advances being made with performance measures in health care can and should be replicated in many other government endeavors. Let’s keep our fingers crossed.