Stephanie Love had been listening politely. But now, she was growing angrier by the minute.

Love, a recently elected member of the Shelby County Board of Education and a mother of four school-age children, was moderating an October community meeting at Denver Elementary School, in the north Memphis neighborhood of Frayser. Three weeks earlier, the state Achievement School District (ASD), which had the authority to take control of any public school whose test scores place it in the bottom 5 percent of schools, had announced that 12 Memphis schools were candidates for takeovers and could be transferred to charter school operators. Denver Elementary was one of them.

The atmosphere was charged. Two days earlier the ASD had held its first community meeting at Raleigh-Egypt High School. It announced plans to give the school to a charter operator. That plan had rankled community leaders because it seemed to undo a reform plan the county school superintendent, Dorsey Hopson, had put in place with the help of community leaders and state Rep. Antonio Parkinson. Together they had interviewed, selected and hired a new principal for the school. When Hopson and Parkinson heard that Raleigh-Egypt High might be assigned to a charter school operator, they urged the ASD to give the new principal and the school a chance to succeed. That advice had been disregarded. Instead, the ASD had decided, as Love saw it, to step “into a war zone.” Not surprisingly, the meeting had been a raucous one. Love had gone so far as to liken the ASD leaders to “terrorists” -- to the apparent approval of many of the teachers in the audience.

Before the Denver Elementary meeting, Love had promised two charter operators scheduled to present that evening that they would be received respectfully, as long as they behaved with civility in return. But when a charter school operator seemed to criticize past educational outcomes at some county-run schools, Love jumped up. “I told you to be respectful,” she said as she walked to the front of the room, visibly agitated. “You are not going to say anything bad about anyone in this building.”

A cluster of teachers, holding hand-lettered signs of “No to ASD” and “Not Underperforming, Progressing; Know the Difference!,” applauded.

Love had had enough of the ASD takeovers. The ASD had already put 22 schools in Memphis under its control -- six of them, including Frayser High, in Love’s neighborhood. Five were operated directly by the ASD, but the rest had been converted to charter schools. Some, but not all, of the first charter schools were posting impressive results. To Love and other community leaders, the process of “matching” traditional neighborhood schools with charter operators seemed arbitrary. The ASD talked about its desire for community buy-in, then announced “matches” that ignored the request of community leaders. “I know this school district, and we’re mad as hell,” Love says, by way of explaining what she sees happening in her community. “We’re mad that everybody knows what’s best for us. We’re mad that the ASD came in and took over several schools, and they’re not improving.”

There was even greater anger at the growing role of charter schools in the ASD takeover plans. “Everybody says [the ASD charters] are the best thing for our children,” Love says. “I say it’s about the money.” Since per-child state education dollars follow the child to whichever public school the child attends, Love questions why charter organizations seem to be interested only in schools with higher enrollments. “Is it really about the low-performing student, or is it about how many kids are in the school?” she asks.

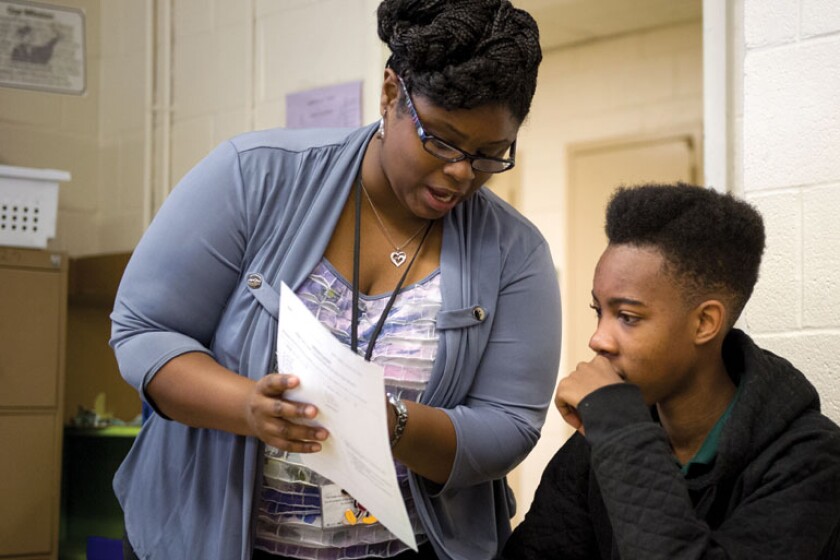

“I know this school district,” says Stephanie Love, “and we’re mad as hell.” (Brandon Dill)

Love is determined to resist the ASD takeovers. She supports an idea put forward by Shelby County Board of Education Chairperson Teresa Jones to expand transportation options so that families whose neighborhood schools have been taken over by the ASD or a charter operator can send their children elsewhere.

As for herself, Love vows she would never send her four children to a school run by the ASD. Her anti-ASD feelings come with a caveat, however. Two of Love’s children attend Frayser High School, which the ASD had transferred to a charter operator that summer. The charter’s founder, Bobby White, renamed the high school MLK College Prep.

For Love, though, MLK College Prep is different. It is run by White, who grew up and worked for years in Frayser schools. Far from objecting to the takeover of Frayser High by White’s fledgling charter organization, Love is eager to see it expand. In two years, her fourth-grade daughter will be heading to middle school. Love doesn’t want to send her to any of Frayser’s current middle schools. But if White’s charter organization were allowed to take one over, Love would send her there.

Love’s attitude toward the ASD personifies the ambivalence of a significant portion of north Memphis residents -- and of other communities nationwide facing similar school reform actions. There is a deep suspicion of the charter school movement, which is widely seen in Memphis’ minority community as being a stalking horse for outsiders to privatize public schools. There is frustration and fear, particularly among teachers who typically lose their jobs when the ASD takes over. There is confusion for parents who don’t know what is happening to the schools their children attend and to the education institutions that have been at the center of their communities.

But there is also hope -- hope that somehow their children will receive a better education than they did. For Love in particular, the hope is that one charter school organization -- Bobby White’s -- will take on more schools. That in turn will depend on what he and the teachers and administrators at MLK College Prep can achieve.

As students accepted that expectations really had changed at MLK College Prep, says ninth grade teacher Trione Vincent, the school’s climate changed. (Brandon Dill)

MLK College Prep is perhaps the ASD’s most ambitious turnaround project. Unlike most charter school operators -- who typically start small, often with a single grade, establish their culture, and then expand slowly with students who apply to the school -- founder Bobby White and principal Kimberly Hopkins-Clark are attempting a whole-school turnaround. In other words, their charter organization, Frayser Community Schools, is taking over the existing neighborhood school and its students all at once.

White is confident he can make it work. He has done turnarounds before, most recently at a nearby middle school. In the past, it had taken him about three years to change the culture and demonstrate significant academic achievements. But at MLK College Prep, White and Hopkins-Clark are hoping to achieve impressive results much faster. They are aiming for double-digit growth in end-of-course test scores over a single school year. “The reason it took me three years when I was a district principal was because I was not able to replace staff or make decisions on the fly,” says White. At MLK College Prep he can -- and he has.

The first difficulty White and his team faced this school year was figuring out how to run the school with no central district to call on when mechanical systems broke or extra services were needed. Establishing a safe decorous environment was a challenge too. “The first week was a honeymoon,” recalls White. “It always is.” The second week was when students began to test the rules. In the beginning, White and his team fielded five to seven “code one” radio calls an hour. These were requests from teachers for in-person support from an administrator. By the end of October, the number of code ones had fallen to just one or two an hour. According to Trione Vincent, MLK’s ninth-grade algebra teacher, that has had a profound impact on what happens inside the classroom.

Vincent is one of MLK College Prep’s more experienced teachers. A graduate of Fisk and Vanderbilt universities in Nashville, she moved to Memphis in 2006 and taught math at a middle school. In 2012, she became the ninth-grade math teacher at Frayser High School. At the time, Frayser had a reputation as a tough school to work in. The students were described to Vincent as “extremely rowdy.” She was told that she would need to have a backbone to handle them. She quickly installed order and soon began to enjoy teaching Frayser students.

But not every teacher did. Some teachers, Vincent says, lost the drive to push the kids to be the best they could be. Expectations were stated but not uniformly enforced. When Vincent upheld high standards in her classroom, some students saw her as capricious and pushed back. The result was a classroom environment where learning sometimes seemed like a punishment.

When Frayser High School became MLK College Prep last fall, that changed. Behavioral and academic expectations were set higher than they had been in the past, and they were strictly enforced. Homework requirements increased. At first, some students resisted, but over time most came around. Vincent points to the experience of one student who had failed English and biology and generally caused trouble last year. In the fall, he came by to show her his report card. He’d made a C in one class; the rest were A’s and B’s. “This was a drastic improvement for him,” says Vincent. The student confided that things at the school “were much better this year.” That, she continues, “has caused him to raise the bar for himself.” To her, that’s an academic testament, as well as a behavior testament. “He’s improved solely because the expectation is higher,” she says. As students accepted that expectations really had changed, the climate changed. As the climate changed, teaching became easier.

Easier -- but still not easy. Teaching at MLK College Prep was a big challenge for many of the school’s instructors, a group for whom the average experience teaching was about four years. At the start of the school year, it become clear that some of the teachers needed extra support. Principal Hopkins-Clark set up a teacher support program that ensured that each week every teacher in the building was observed in class and given feedback by a member of the administrative team. But White worried that that wasn’t enough for some of his teachers. So, as the fall semester progressed, he hired a recently retired Shelby County Schools principal to spend three days a week working with the 10 teachers who needed the support most.

Parents such as Love noticed the overall changes at the school. Two of her children are students at MLK College Prep. White, she says approvingly, “holds them accountable.” The school is also offering new opportunities. “My ninth-grader is in an honors program [this year],” Love says. “There were no honors programs last year.”

Shelby County Board of Education Chairperson Teresa Jones has offered to expand transportation options so that families can send their children elsewhere. (Brandon Dill)

In years past, the ASD’s takeover announcements had generated impassioned protests from some parents and teachers who faced the prospect of losing their jobs if the ASD or a charter operator took over. But none of the protests were well organized or had much of an effect. This year, with Love, state Rep. Parkinson and other leaders taking charge, a different tone has been set.

Whether because of the protests, which were covered extensively by the media, or other misunderstandings, several charter school operators have begun to pull out of the ASD’s matching process -- even though in some instances their matches with priority schools had already been made public. The Knowledge is Power Program (KIPP), one of the best regarded charter school organizations in the nation, for example, decided not to take over South Side Middle School. KIPP Memphis Executive Director Jamal McCall said that he had believed that Shelby County Schools intended to close South Side, meaning KIPP could move into an empty building. “When we realized the building wasn’t going to be closed, we realized that wouldn’t work,” McCall says. “We would have to absorb more than one grade at a time,” a deviation from the KIPP model that McCall wouldn’t make.

But the most direct example of the protests having an impact came with Raleigh-Egypt High School. In early November, after a week of well-publicized protests, Raleigh-Egypt’s charter school match, Green Dot, announced that it was withdrawing. Green Dot wasn’t afraid of protests, says Memphis Director Megan Quaile, it was the political dynamic. “We felt we didn’t have the bandwidth to do the level of community outreach we were going to need to do given that this was in the media every week,” she says. “We didn’t have the ground support to do it right, and to make sure that kids could get a great opportunity, or have a positive transition experience.”

ASD Superintendent Chris Barbic wasn’t upset by the attacks on his record -- on the gains his schools have or haven’t produced. “The fact that people bring facts to these conversations, it’s awesome,” Barbic says. “People want to hold our schools accountable.” But he did blame himself for some of the tumult and for the perception that the ASD was retreating under pressure from protests. Barbic, 44, had suffered a heart attack in September and had been absent for several months. As he recovered his health and “tried to reintegrate into work,” he feels he may have missed the chance to shape perceptions of the charter operator pull-outs. He points to Green Dot, a charter school operator that is already serving 1,200 kids in Tennessee after only two years operating in the state. “It’s not like these guys are going slow. They’re new to town. How much do you want your name dragged through the mud when you first get here? All these guys are playing the long game. They want to be here forever. They want to have relationships.”

Barbic’s also planning to work harder on long-term relationships. He wants to coordinate more closely with Shelby County Schools about future school closings -- and with the communities whose schools might be candidates for state intervention.

He also has to ensure the ASD’s future. Since its creation in 2002, the 35-person central office has been funded by federal dollars -- money that runs out this summer. To replace it, Barbic needs to raise about $4.5 million from the state legislature at a time when the politics of education are changing. In mid-November, for instance, Tennessee Education Commissioner Kevin Huffman, who had been a strong advocate for Tennessee’s education reform movement, announced that he was resigning.

Superintendent Dorsey Hopson, left, had urged the ASD not to take over Raleigh-Egypt High School. (Brandon Dill)

In the end though, what the ASD really needs are more wins -- more clear-cut, impressive successes that would quiet the critics. At MLK College Prep, the administration would have the first in-house assessment scores in February. No one knew what effect the school’s improving atmosphere would have on student scores. What White and his staff did know was that the school’s environment was changing for the better.

For White, just how much it has changed became clear on Dec. 21. He and Hopkins-Clark had decided to celebrate the holidays by doing something unusual -- gathering the entire school in the auditorium for a holiday performance. In most schools, this would have been no big deal. In the former Frayser High, such schoolwide assemblies simply hadn’t been done, largely out of safety concerns. But White and Hopkins-Clark thought the students were ready for it.

The event began with a performance of “Silent Night.” A female student began to sing, but she was way off key. White had seated himself near the front of the audience, the better to keep an eye on the student body. When the off-key sounded, White worried it would provoke catcalls and laughter. He slowly stood up so as to be more visible. But the 600-plus students sat quietly in MLK College Prep’s cavernous auditorium. At the end of the song, they applauded.

Throughout the 2014-2015 school year, Governing has tracked efforts to turn around one Memphis, Tenn., high school. This is the third installment in a four-part series; the other parts can be found at governing.com/frayser.

*This article has been updated to reflect the fact that Frayser Community Schools and Green Dot are charter school operators, not companies.