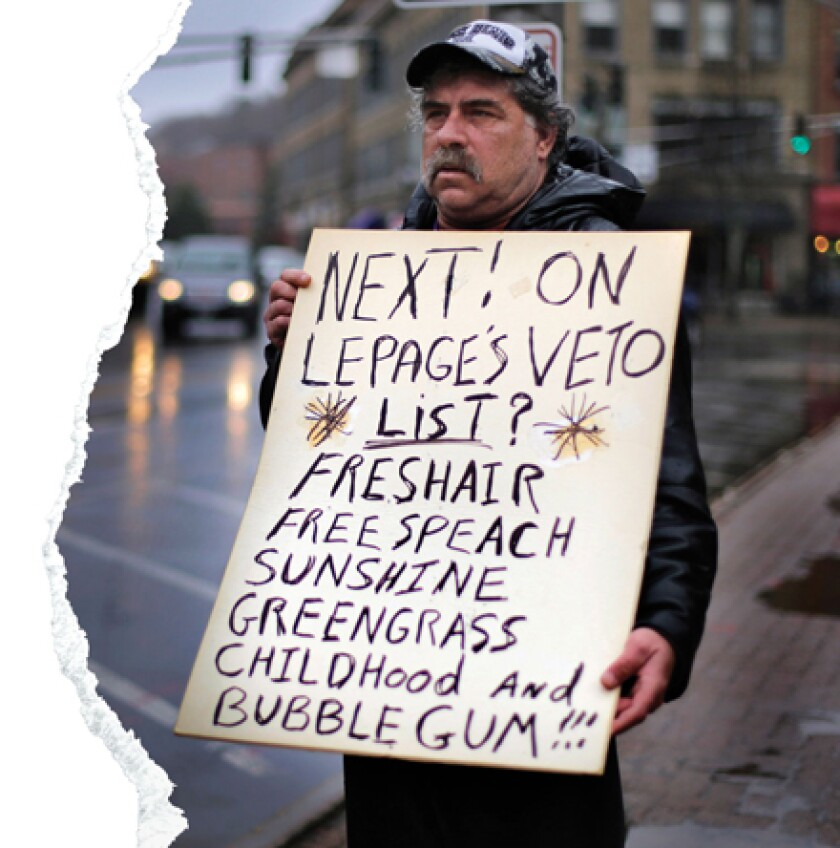

An impeachment effort that was bound to lose and a governor refusing to give a speech may seem like symbolic sideshows, but they demonstrated pretty clearly that relations between LePage and the legislature aren’t improving. They could hardly be much worse. Last year, LePage decided toward the end of the session to veto every single bill the legislature sent him. He was angry that lawmakers wouldn’t put before voters his proposal to eliminate the state income tax. In the end, the governor vetoed a total of nearly 170 bills. He would have vetoed dozens more, but the state Supreme Judicial Court ruled that he missed the deadline for rejecting 65 others.

The legislature was able to override about 70 percent of LePage’s vetoes, casting votes that at least made it possible for the state to have a budget for the current year. Power in the legislature itself is divided between a Democratic House and a Republican Senate, but by refusing to sign anything, LePage temporarily unified the two parties.

Divided government is always challenging, but what is happening in Maine right now goes far beyond any conventional notion of divided government or partisan competition. It is an exercise in extreme political hostility, in which even the most routine give-and-take between the executive and the legislative branches has disappeared. Faced with an obstinate chief executive, legislators are essentially trying to run the state on their own. The only positive by-product of this has been a tenuous coalition of Democratic and Republican legislators willing to work together to prevent the situation from deteriorating even further. “In terms of creating law, we’ve done that in the absence of a governor,” says Mark Eves, the Democratic speaker of the House. “It’s too bad, but it doesn’t stop us from working together.”

It didn’t help matters last year when LePage blackballed Eves for a job, threatening to cut off funding for a charter school that wanted to hire the speaker. The atmosphere of mutual distrust has carried over into this year. The governor has signed some bills, but legislators are proceeding with the expectation that he might decide to block any bill for any reason. Therefore, nothing much is going to move unless it commands overwhelming veto-proof support from both parties in both chambers. “Everybody recognizes that you’d better have bipartisan support from the beginning and throughout if you’re going to be successful,” Eves says, “because you’ll have to overcome the governor’s veto.”

That’s already happened in some cases. Legislators gave unanimous approval to a conservation bond package LePage had fought, as well as a bill that addresses the state’s drug addiction crisis. The latter package won unanimous approval from both the House and Senate, and LePage signed it. Despite all the conflict, some work does get done. A few bills are being entered into law.

Republican Gov. Paul LePage, right, and Democratic Speaker of the House Mark Eves before a fight that led to an atmosphere of mutual distrust that has carried over into this year.

With the entire legislature up for election this year, Republican lawmakers now face a stark choice. Their normal inclination would be to side with the governor of their own party. LePage is seeking to promote that line of thinking by taking his case directly to the people, holding town hall meetings on a nearly weekly basis and working hard to recruit candidates he considers supportive -- even if that means finding challengers to run against incumbent Republicans. “The more the governor is able to talk about his priorities and articulate them to the people of Maine, the more the legislature is willing to listen,” says Adrienne Bennett, LePage’s press secretary.

But some Republicans -- knowing that LePage was elected twice with less than a majority vote and that he remains a controversial figure because of his unwillingness to make deals and his tendency to make offensive statements -- are deciding they don’t want to run as LePage Republicans. “Everyone, including Republicans, are individually sizing up what kind of impact this governor will have on their individual races,” says GOP state Sen. Roger Katz, “and how closely they do or don’t want to be aligned with him as a result. That’s 186 different calculations going on.”

As legislators and the governor look ahead to the election, no one is happy about the present situation. LePage has been hemmed in. His own wish list, most notably stricter rules for social welfare programs and abolition of the income tax, has little chance of getting a serious hearing. “The five years of his administration have been a series of missed opportunities,” says Katz. The Republican senator has sometimes crossed swords with LePage, but describes the governor’s failure to push his priorities more deftly as a tragedy. “We could have moved his agenda forward in a much more robust way if there had been more civility and more give and take between his office and the legislature,” Katz says.

It’s not as though the governor has completely dealt himself out of the process. When it comes to running the executive branch, LePage has exercised tight control, not allowing his agency heads to veer off the course he sets. He does his best to prevent them even from testifying before the legislature, except in carefully controlled circumstances. In an extreme instance last month, LePage announced he would take on the duties of education commissioner himself, since it looked like Senate Democrats were gong to torpedo his pick. Legislators say that they have been given a serious lesson in what separation of powers really means, since it’s impossible for them to craft laws in a way that anticipates every administrative roadblock the governor might put up. “When he decides he doesn’t like something, he can use a lot of obstacles,” says former GOP state Sen. David Trahan.

And while anti-LePage legislators have demonstrated that legislative vetoes can be overridden, they haven’t been able to do it every time. As a result, strategic thinking about legislation in Maine looks a lot different than it does in other states. Only issues of primary importance are likely to be addressed. Smaller matters lack an engaged constituency and the momentum necessary to get things through the state’s unique intragovernmental maze.

Even major issues that everyone agrees must be addressed, such as the state’s heroin epidemic, don’t call out as much legislative firepower or brainpower as they would normally demand. With supermajority support serving as the minimum needed to bring legislation forward, bills simply can’t be as complicated or comprehensive as sponsors might otherwise want. Legislators and lobbyists alike are left seeking the lowest common denominator. Anything that is deemed too ambitious doesn’t go anywhere. “It’s hard to do anything innovative,” says Beth Ahearn, political director for the Maine Conservation Fund, “when the governor is going to veto and overrides are hard.”

Environmentalists have mostly spent the LePage years in a defensive crouch, but in one area they have been able to seize the initiative. In both 2010 and 2012, Maine voters overwhelmingly approved millions of dollars in conservation bonds for a program called Land for Maine’s Future. Despite this show of public support, LePage refused to issue the bonds, blocking the funds unless he could get his way on other matters, such as payment of hospital debt and timber harvesting on public lands to pay for low-income heating assistance.

Last year, legislators decided to order the governor to issue the bonds. They had no trouble winning big majorities in favor of the idea. But under intense pressure from the governor’s office, a half-dozen Republicans flipped their votes, sustaining LePage’s veto.

Heading into this year’s session, advocates for the land program used every trick in the lobbyists’ handbook to gain support. Environmentalists and hunters built up a coalition of conservative and liberal lawmakers willing to press for the conservation bonds within each caucus. They commissioned a poll showing that 74 percent of Maine residents support the conservation program. Legislators who had switched their votes received pressure from their home districts. “They were pounded on, publicly and privately,” says Ahearn. “They went to the governor and said, ‘You’re killing us on this issue.’”

When it came time for a vote this January, House Democrats left their GOP colleagues no choice -- agree to fund the popular program for five years, or don’t fund it at all. They refused to allow a vote on LePage’s proposal to issue bonds for only six months. Ken Fredette, the Republican leader, was visibly torn as he explained his decision to support the Democratic measure on the House floor. “That was not a coincidence that he felt he was in a box,” says Trahan, now the executive director of the Sportsman’s Alliance of Maine. “We put him in a box.”

It was a successful strategy for bypassing an implacable governor. But the sequence of events also showed how difficult it is to pull that kind of thing off. Not every bill can boast of support that is both intense and widespread. Consider the drug epidemic. Maine has seen spiking numbers of people addicted to opioids. Last year produced a record number of overdose deaths.

LePage has been hammering away at this issue for years. He was addressing the topic at a town hall in Bridgton on Jan. 6 when he made his most recent set of widely condemned remarks, saying that traffickers “by the name D-Money, Smoothie, Shifty” come to Maine from Connecticut and New York to sell heroin and “incidentally, half the time they impregnate a young, white girl before they leave.” Strikingly, local reporters, inured to the tone of LePage’s rhetoric, failed at first to highlight the remark. But amidst the subsequent national media uproar, LePage apologized to “Maine women.”

Several politicians said that LePage had unnecessarily diverted attention from a serious issue, but the real holdup when it comes to passing drug legislation in Maine is a philosophical difference of opinion. LePage wants to see stepped up enforcement, with more agents hired at the Maine Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). He also commented recently that the state ought to “bring the guillotine back” for executing drug traffickers.

Maine Democrats believe the situation must also be addressed on the demand side, through expanded and improved treatment and recovery programs. LePage has not accepted this. Last summer, he refused to apply for federal grants that could have provided $3 million for drug treatment in Maine. The day before his Bridgton appearance, the governor complained in a radio address that a legislative proposal included “money and special favors for their friends. The bill sends money for drug treatment to hand-picked organizations whose programs have been ineffective.”

While Democrats favor stepped-up treatment, they certainly aren’t against enforcement (even if they don’t like guillotines). It’s not hard to see where a compromise could be reached -- more money for enforcement, more money for carefully screened treatment programs. But that’s not the way things are done in Maine these days.

Instead, legislators quickly moved a drug treatment package in January that its own sponsors described as inadequate, a down payment at best. The package calls for hiring 10 more DEA agents, with $2.5 million more for treatment. The package as a whole provides only a little more money than LePage turned down last year from the feds. Perhaps because it was so modest, it had no trouble sailing through both chambers with unanimous support. Other bills have been inching their way through the legislative pipeline, but despite recognition on all sides that drug addiction is an issue that deserves a stronger response, agreement has been elusive. “The process has been more unpredictable and fluid than ever,” says Jim Cohen, a former Portland mayor who represents methadone clinics, among other clients. “That’s not to say that every bill will be vetoed, but the safest way to go is to obtain a two-thirds majority of both houses.”

A good compromise, it’s often said, leaves everyone a little dissatisfied. But Maine’s current political system doesn’t allow for typical compromise, with both sides giving a little and working their way through a messy process. Instead, this is the new legislative strategy in Maine: Don’t ask for much, and you may get it. “From the advocacy point of view, people are not putting forward bills that are too ambitious,” says Glen Brand, state director of the Sierra Club.

Legislators and LePage can agree on this much: They aren’t satisfied with the present arrangement. Toward that end, both sides are hoping that this fall’s elections will reshuffle the deck, giving one or the other the chance to claim a mandate from voters.

But it may not be that simple. Partisan control of both chambers has flipped repeatedly in recent cycles. Heading into the election, the margins are tight in both chambers. Higher turnout in a presidential year should favor Democrats. Maine hasn’t supported a Republican presidential candidate since 1988.

On the other hand, Democrats will have to defend a lot more open seats than the GOP -- including some in districts that have supported LePage. “On balance, the governor is inspiring a lot of Republicans to run for office,” says Rick Bennett, the state GOP chair. “A lot of the 43 freshman Republicans in the Maine House ran for office because they want to support his reform agenda.”

For all they’ve been able to cooperate on with Republicans in the legislature thus far, Democrats know that losing majority control of the House would be disastrous for their priorities. For his part, LePage wants the election to serve as a referendum. The governor believes he’s doing the will of the people -- he’s fond of pointing out that, even without a majority, he received more raw votes in 2014 than any gubernatorial candidate in Maine history. He believes that if he maintains his unyielding stance, voters will reward him with a friendlier legislature for the 2017 session.

In the meantime, the legislature will continue to debate and vote, passing modest bills, but only where there is overwhelming consensus. Many frustrated advocates who would like to push more ambitious policies are taking their arguments straight to the ballot, with a broad range of measures already filed for votes this November. Convincing voters of the merits of their cause may be easier work than getting the legislature and the governor to cooperate on anything.