He wasn’t the only one. Addressing the press moments earlier, the irritated Republican minority leader, Themis Klarides, had blasted “the arrogance of the majority” for rushing the legislation through without compromising with the GOP. Aresimowicz fired back against the “idiocracy of the minority,” saying Republicans had held up the bill with frivolous questioning. The New Haven Register described the whole ordeal as “starkly partisan,” “emotional and tense,” with “pointed rebukes and hurt feelings” lingering as Democrats celebrated what they saw as a major victory -- a pay raise for 332,000 state residents. Democratic Gov. Ned Lamont signed the wage hike into law later that month. It will be phased in over a period of years, reaching the full $15 in 2023.

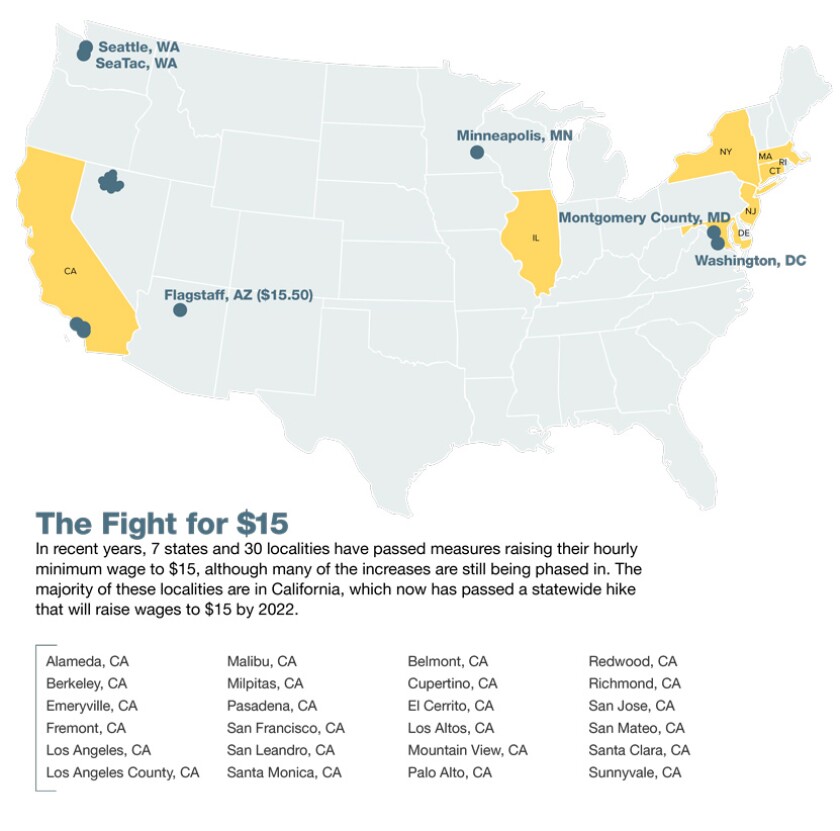

Connecticut thus became the seventh state in the nation to embrace $15 for its workers, following California and New York in 2016, Massachusetts in 2018, and Illinois, Maryland and New Jersey earlier this year. These increases, all of which will be phased in over time, are taking place as support for the $15 wage has become thoroughly mainstream among national Democrats, with all their leading presidential candidates for 2020 backing that wage as a federal standard.

The U.S. House passed a federal $15-an-hour bill this summer, although it is unlikely to become law. The Labor Department under President Trump has said it opposes any increase to the federal minimum wage.

Will this policy expand beyond the country’s bluest enclaves? Progressives think so. They cite research suggesting that minimum-wage increases tend to raise incomes overall and lift Americans out of poverty even if they cost some workers their jobs.

Yet with the federal minimum wage currently standing at $7.25 an hour, Republicans, many businesses and even some Democrats will continue to argue that a jump to $15 is too drastic, especially when it’s a one-size-fits-all approach implemented from coast to coast. If the all-nighter at the Connecticut Legislature is any indication, these arguments will be intense -- evidence of an emboldened Democratic Party but also, unavoidably, of deeply divided national politics. “This debate really brought to my attention just how polarized we are,” says Connecticut Rep. Robyn Porter, a Democrat who led the charge to raise the wage.

Funded primarily by the Service Employees International Union, the “Fight for $15” campaign began in 2012, a year after Occupy Wall Street protests elevated the issue of economic inequality in the national consciousness. Hundreds of fast-food workers in New York City walked off their jobs in late November of that year, demanding a raise from $7.25 to $15 and the right to form a union. Earlier that month, Walmart employees across the country walked out on Black Friday, the busiest shopping day of the year. It was a moment when low-wage service and retail organizing “really seemed to be exploding,” Columbia University public affairs professor Liza Featherstone told a reporter.

The ensuing years brought strikes in hundreds of cities. Some municipalities adopted $15 on their own, particularly on the West Coast, beginning in 2013 with SeaTac, Wash. Organizers in SeaTac were frustrated with their inability to win higher wages for workers at the Seattle–Tacoma International Airport through labor-management negotiations, so they lobbied the city council to raise the minimum wage. After that failed, they went directly to voters with a ballot initiative, eking out passage by 77 votes. “SeaTac will be viewed someday as the vanguard, as the place where the fight started,” David Rolf, the campaign’s lead organizer, told supporters after their victory.

The movement went on to victories in Seattle and Washington, D.C., as well as a group of California cities that included Berkeley, Los Angeles, Palo Alto, Pasadena, San Francisco, San Jose and Santa Monica. Then-California Gov. Jerry Brown and New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo were the first to sign statewide laws, approving their respective measures on the same day -- April 4, 2016.

Appearing at Cuomo’s celebratory rally in Manhattan, Hillary Clinton praised the Fight for $15 and predicted its achievement in New York would be replicated across the nation. “It’s a result of what is best about New York and best about America,” she said. “I know it’s going to sweep our country.” Bernie Sanders, then Clinton’s rival for the Democratic presidential nomination, said in a statement that he was “proud that today two of our largest states will be increasing the minimum wage to a living wage.” President Barack Obama issued his own statement, praising New York’s law as a “historic step.”

In California, Brown embraced $15 with some hesitation, negotiating a compromise with lawmakers allowing the governor to delay the wage hike in the event of an economic downturn. Brown said somewhat cryptically at his signing ceremony that “economically, minimum wages may not make sense, but morally and socially and politically they make every sense, because it binds the community together.”

Another governor who signed compromise legislation for $15 was Republican Charlie Baker in Massachusetts. He forged a “grand bargain” with lawmakers to keep questions about the minimum wage, paid family leave and a sales tax increase off the ballot last fall. In Maryland, meanwhile, lawmakers overrode Republican Gov. Larry Hogan’s veto to get to their $15 rate, and he wasn’t pleased. “Maryland had just increased its minimum wage four years in a row,” Hogan said, “by nearly 40 percent, to $10.10, which was already by far the highest in the region and one of the highest in the nation, [and now they are] inflating our state’s minimum wage to more than double that of Virginia, which is at $7.25. It makes it very difficult for us to compete, and it could simply be too much for our economy to bear. A 48 percent increase in costs could be crippling to some of our small mom-and-pop businesses.”

But proponents say $15 has been a vital lifeline for some of the most vulnerable workers. By the end of last year, 22 million low-wage workers had won $68 billion in pay increases, according to an analysis by the National Employment Law Project (NELP), which supports higher minimum wages. “Of the $68 billion in additional income,” NELP claimed, “the overwhelming share (70 percent, or $47 billion) is the result of $15 minimum-wage laws that the Fight for $15 won in California, New York, Massachusetts, Los Angeles, San Jose, San Francisco, the District of Columbia, Seattle, and numerous other places.” Meanwhile, major companies including Disney and Bank of America got on the $15 bandwagon, and McDonald’s -- one of the low-paying businesses that prompted the Fight for $15 in the first place -- announced this past March that it would no longer lobby against federal, state or local minimum-wage increases.

All of that was historic, says Leo Gertner, a staff attorney at NELP, “because, for so many decades, the minimum wage in terms of real value was stagnant -- if not declining -- while CEO pay grew.”

The perennial criticism of minimum-wage increases is that they end up killing jobs by saddling businesses with extra expense. Michael Saltsman, managing director of the conservative Employment Policies Institute, which is linked to the restaurant industry, argues this is especially true with the Fight for $15. “The difference in this latest iteration of the minimum-wage debate,” he says, “is that the wage demand for $15 is so far above any sort of historical standard we have. The consequences have been accordingly more severe.”

“Our biggest concern was not Walmart, Target, CVS, Walgreens,” says Klarides, the Connecticut Republican leader. “They can absorb this, but the mom-and-pop shops on Main Street can’t. Those are the places that have been suffering at the hands of the state of Connecticut for many years now. Those are the people that can’t take it anymore. It’s like a button on a shirt that’s been pulled and pulled, and it’s just gonna snap.”

Connecticut House Minority Leader Themis Klarides is opposed to the $15 minimum wage. (David Kidd)

Saltsman, who believes any increase in the minimum wage is “a counterproductive policy,” says some businesses are already snapping. He points to Emeryville, Calif., which -- as of this spring -- was considering a moratorium on its plan to go from $15 to $16.30, following complaints from local businesses. Opponents of the $15 wage also cite a Harvard Business School working paper from 2017, called “Survival of the Fittest: The Impact of the Minimum Wage on Firm Exit.” That paper examined business closures -- or “exits” -- in cities in the San Francisco Bay Area. The findings “suggest that a one-dollar increase in the minimum wage leads to a 14 percent increase in the likelihood of exit for a 3.5-star restaurant (which is the median rating on Yelp).” However, restaurants with higher Yelp reviews appeared to weather minimum-wage increases reasonably well, suggesting the pay hikes mostly brought negative consequences for establishments with less-than-stellar reputations.

Minimum-wage studies have varied over the past 30 years. But the consensus among mainstream economists now seems to center on two points. One is that raising the minimum wage not only increases the average income of low-wage workers, but lifts some of them out of poverty (depending on how big the raise is). The other is that some workers do lose their jobs as a result of a minimum-wage boost. In 2014, the Congressional Budget Office published a report estimating that a federal rate of $10.10 would cost the economy roughly 500,000 jobs. But a series of analyses from Michigan State University, the University of Massachusetts and University College London have found only a small impact on employment. “For decades now, studies have shown no adverse impact for increasing wages and increasingly the proof is in the pudding,” insists Gertner of NELP. “The states that have increased their minimum wages gradually, as the federal bill would do, have not seen the sky fall. What we’re seeing from the folks saying $15 is too high are just scare tactics, because they don’t want to share prosperity with workers. It can be done. It’s practical, pragmatic and simple, and it has enormous benefits for businesses.”

“When you put disposable income in the pockets of everyday working people, that money comes right back to the local economy,” says Porter, the Connecticut Democrat.

(AP)

This isn’t to say all Democrats are on board, as this summer’s debate in Congress made clear. The Democrat-led U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill for $15 in mid-July, but some moderate Democrats have argued for a regional approach, to account for different costs of living in different communities. Supporters of the national minimum warn that this approach would lock the lower cost-of-living states into being low-wage states for the foreseeable future. But the divisions among House Democrats suggest that the politics of $15 are more complicated than they appear. “It’s easy for Democratic presidential candidates to make those kind of broad pronouncements right now because they need to do so to get labor behind them,” Saltsman says. “It’s a consequence-free promise they don’t have to make good on. When someone like that got into office and started hearing concerns from moderate Democrats, they might be singing a different tune.”

Gertner doesn’t sound worried. “In large cities where jobs are concentrated, housing costs have far outpaced the minimum wage,” he notes, arguing that the number actually should be $20 or $22 someday. “It’s not unreasonable to float those numbers. We’re just saying that $15 is the absolute minimum. In high cost-of-living states like Connecticut, it’s a no-brainer.”

“This ain’t the three-pointer,” says Porter, “but we can give ’em a layup shot. We can get them a little closer to where they need to be.” NELP is already eyeing Connecticut’s neighbors, Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine, as the next frontiers.

What Connecticut has shown, though, is that $15 isn’t yet a given, even in blue America -- and it certainly doesn’t come easily. Democrats recently expanded their presence in the Connecticut Legislature, and half the House Democratic caucus identifies as progressive. Yet the wage increase was painfully difficult to enact. In Porter’s view, the Democrats have lacked the confidence to pass bold initiatives of that sort. “We claimed to be a progressive state, and I just expected that we would have gotten a lot more progressive bills through this year,” she says.

Klarides, unsurprisingly, sees this shift to the left differently.

She views the new progressives as making the House more ideological, rigid and uncivil. “They’re just following a national playbook,” she says. “They’re not taking into account the needs, concerns and problems of Connecticut.”

When the signing ceremony for the $15-an-hour wage arrived, Porter struck a personal note, reminding the crowd that she had been “that single mom raising two kids, working three jobs,” who would benefit from getting a raise. “I am thrilled that we are standing here today and we can say with great pride and great humility that we did this together,” she said. But she expressed her hope “that the rest of the states will jump on board, and that it won’t be the fight it was in Connecticut.”

In this political environment, that seems far from certain.