It is a gruesome reality for Charles West, the city’s criminal justice coordinator and chief architect of Mayor Mitch Landrieu’s violence-reduction strategy. West leads a team of innovation specialists who help city agencies devise new strategies to address key priorities identified by Landrieu. In 2012, Landrieu tasked them with bringing down the murder rate. There was no bigger problem than that. There still isn’t.

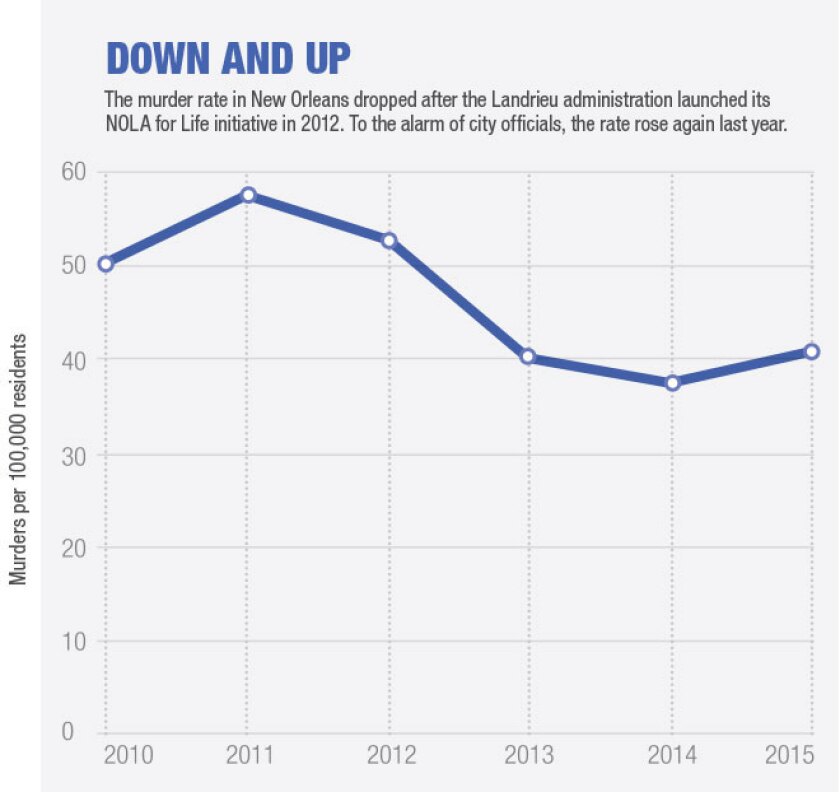

Crime is a perennial issue in every American city, and most mayors make public safety a cornerstone of their administration. Few, however, have devoted as much time and attention to homicide as Landrieu has in the past five years. When he became mayor in 2010, New Orleans had more murders per capita than any city of more than 100,000 people. With grant funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies, Landrieu hired a team of in-house consultants, headed by West, to devise a comprehensive anti-homicide program. What emerged was NOLA for Life, a cross-agency initiative that aims to help young black men from low-income neighborhoods avoid violent crime, while also cracking down on a small group of ringleaders responsible for most of the murders in the city.

“From a moral perspective,” says Landrieu, “you cannot accept the reality that young men are being killed at catastrophic levels on the streets. I just thought it was the most important problem I could think of. It was as complicated as any, and nobody has yet found an answer to it.”

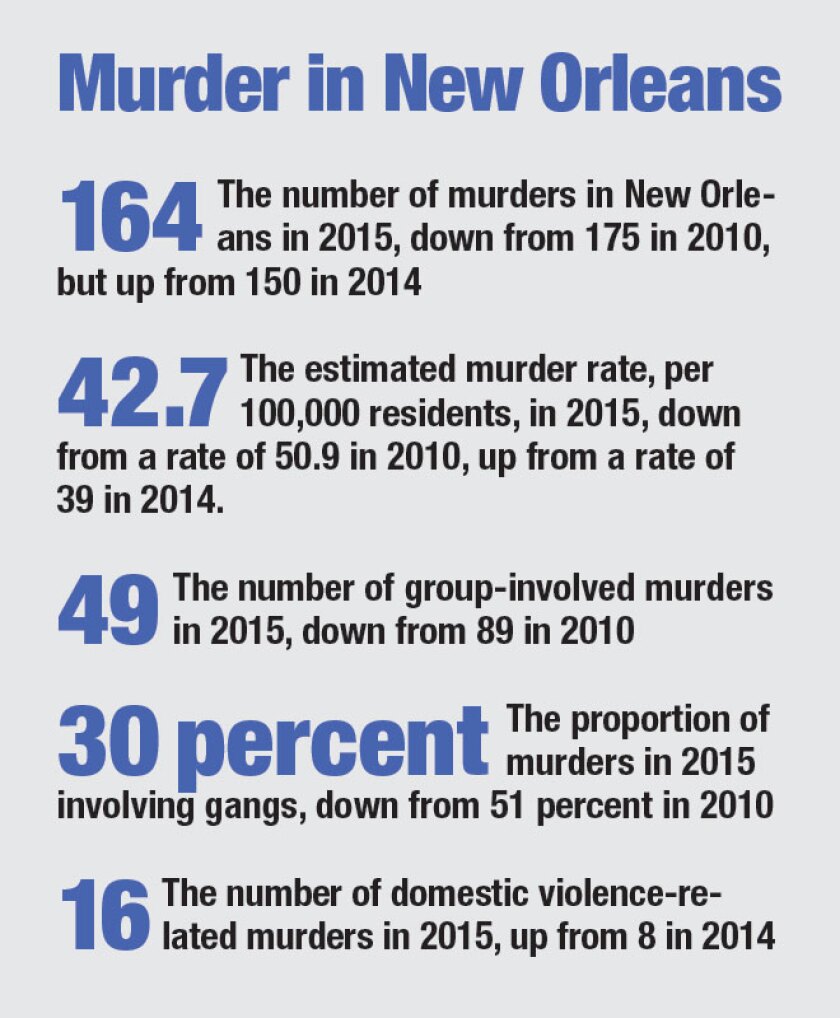

Landrieu’s own staff questioned whether it made sense to stake so much political capital on a problem driven by forces largely outside the mayor’s control -- poverty, unemployment, substandard education, inadequate housing and regional migration trends. Ashleigh Gardere, the mayor’s economic development director, says that when Landrieu announced that the innovation team would focus on murders, “My response was, ‘Why would we do that? We can’t even win.’” And yet, to the surprise of many, they started to win. In the first year NOLA for Life came online, the number of annual murders dropped from 193 to 156. The next year, it dropped to 150.

Since 2012, the mayor’s innovation team has committed itself to track every single murder in the Crescent City. Hence, the emails. The one team member who doesn’t get them, surprisingly, is West. He decided to skip the unpleasant experience of seeing the city’s annual murder count rise in real time. “We all have a desire to see people live their lives to the fullest, to not fall prey to violence,” he says. “We are all affected personally by the work. But I want to stay focused on the larger trends.”

The calm, soft-spoken West, who is 36 years old, prizes long-term data over the isolated anecdote, historical context over the latest trend piece in the local paper. Even so, the first quarter of 2015 tested his resolve to focus on the big picture. After three consecutive years of decline, murders were up 73 percent compared to the first three months of the previous year. After patient monitoring of the data, says West, “we see this spike. Then the question becomes, well, what do we do about it?”

Susan Poag/Digital Roux Photogra/Susan Poag/ Digital Roux Photogr

"We are all affected personally by the work," says Charles West. "But I want to stay focused on the larger trends." (Susan Poag/Digital Roux Photography)

Last year, city officials in much of the country were asking themselves the same question. For the most part, violent crime had been dropping steadily in urban America over the previous two decades. Then police departments started to see a worrisome reversal of that trend. By late August, New Orleans was among several major cities on pace to see a double-digit percentage increase in the number of murders compared to the year before.

For 2015 as a whole, murder rates rose an average of 14.5 percent across 25 of the 30 largest U.S. cities, according to an analysis by the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University. In New Orleans, murders ended up 9 percent higher. The Brennan Center’s researchers caution that because annual murder counts have declined so much since the 1990s, a small change in the actual number can look more dramatic than it really is. In Portland, Ore., for example, five additional murders translated to a 19.2 percent increase. In Denver, 23 additional murders meant a 74.2 percent increase.

Still, no one knows why homicide made a comeback in some cities last year, or whether it was the start of a more sustained and troubling trend. Some say public outrage over police brutality discouraged officers from confronting and arresting violent criminals. In many cities dealing with financial pressures, insufficient police pay and benefits may have led to shortages of experienced officers needed to investigate murders and catch especially dangerous people. Another theory is that gang members were killing each other to gain control of the growing synthetic drug market.

In New Orleans, Landrieu has framed last year’s uptick as a small setback, but not a reason to panic. “One murder is too many and a statistic has no meaning to a family member,” he says. “But when you’re redesigning an entire system to make murders go down, it matters a lot whether the statistics have gone up 50 percent or 9 percent.” It was a more sober assessment than the one Landrieu made the year before, when his office trumpeted a 43-year “historic” low in murder. The decline in murders had become a signature achievement of the Landrieu administration, proof that a community could in fact do something about the most complicated and intractable of urban problems. The rise of murders in 2015 threatened to undermine that inspirational narrative, leaving West and others involved with NOLA for Life to figure out what was going on.

(Source: City of New Orleans)

The strategy that West and his colleagues devised in 2012 to reduce homicides is a sprawling one -- there are 29 discrete programs in NOLA for Life -- but the parts that get the most attention deal with gang violence. Frank Young, a police commander who runs the Multiagency Gang Unit, remembers the incident that prompted officials to dedicate funding and manpower to the gang problem. It happened in 2012. Young was a lieutenant in the Central City neighborhood, a high-crime area, and he heard gunfire a few blocks away. Someone had shot a girl named Briana Allen as she and her family celebrated her fifth birthday on their front porch. Her father, himself a suspected murderer, was the intended target.

In response, Landrieu convened law enforcement officials from the city, the surrounding parishes, and the state and federal government. The purpose of the meeting was to generate new ideas to prevent children from getting shot. Young lugged in a box of reports on violent crimes involving just one family, Brianna Allen’s. Much of the gun violence in Central City could be traced back to them. “There’s nothing I can do,” he recalls telling people in the room. “I don’t have the resources to build a huge conspiracy case.” At that point, an assistant district attorney piped in with a proposal: The city should create a special gang unit with local prosecutors, local law enforcement and federal agents. They would focus on gathering evidence to put the most dangerous offenders in prison.

Anti-gang units are a common feature of large urban police departments, but the conventional wisdom in New Orleans had long been that the city didn’t have organized gangs. What it had were small, informal neighborhood groups. They tended not to have the size or rigid hierarchy of organized gangs. Still, many of the experts believed, they were perpetrating most of the city’s deadly crimes. The time had come to treat them as gangs.

The targets of the Multiagency Gang Unit were locals like the Allen family, neighborhood residents whom police had already encountered in previous shooting incidents. “When a shooting would happen, it was the same people over and over again,” Young says. “Today’s suspect is tomorrow’s victim. Today’s witness is tomorrow’s suspect. It almost became predictable. We kept on seeing the same names.”

The rationale behind the unit was that a core group of troublemakers was involved in a disproportionate share of the shootings. Removing them from the neighborhood through arrests and incarceration might disrupt the cycle of retaliatory murders. Taking advantage of a little-used 30-year-old racketeering statute, the unit’s work has resulted in indictments of 114 people from 12 different gangs on a variety of charges, among them illegal gambling, bribery, drug crimes and gun-related offenses. As the prosecutions ramped up, the number of shootings and murders in the Central City neighborhood steadily declined. Between 2012 and 2015, the incidence of so-called group-involved murders dropped from 114 to 49.

The city has a few other tactics it is using to discourage gang violence. Young’s unit conducts call-ins with offenders on probation, offering them free support services and a warning that if they reoffend, they’ll face aggressive prosecution and a likely prison sentence. Another program, modeled after one called CeaseFire that began in Chicago, uses outreach workers to meet with young people suspected of being involved in shootings. Unlike the gang unit, CeaseFire doesn’t have an enforcement mechanism and its staff members don’t work with police. They tend to be ex-offenders or residents of the same high-crime areas as the people being targeted for assistance.

To some, the spike in murders early last year was evidence that the city’s progress on the problem had been a mirage. “They got lucky,” says Michael Glasser, president of the New Orleans police union.

Glasser believes the drop in murders had nothing to do with the mayor’s programs. He points to the conflicting trends of murder and shootings. While murder declined between 2011 and 2014, the number of shootings fluctuated. “When people are shot,” he says, “whether they live or die has nothing to do with police.” Instead, he credits effective trauma care in hospitals.

While the mayor’s office casts the wide-ranging nature of NOLA for Life as a strength, critics question whether the city can pinpoint what, if anything, actually brings down violent crime. NOLA for Life is dizzying in its breadth, focusing simultaneously on education, health, policing, blighted housing, prisoner re-entry and employment. One program offers free midnight basketball for older teenagers in high-crime neighborhoods. Another provides trauma counseling for K-12 students affected by a recent shooting. Yet another connects young people with summer jobs. “All the things they’re doing are sensible,” says Peter Scharf, a criminologist with Louisiana State University’s School of Public Health. “But sensible may not reduce murder.”

Chuck Billiot

Landrieu: "You cannot accept the reality that young men are being killed at catastrophic levels on the streets." (Chuck Billiot)

Scharf argues that the benefits from social and health programs have been undermined by a shrinking police force. Since Landrieu took office, the police department has lost about a quarter of its officers. A survey of police union membership conducted by Scharf in 2012 found that officers felt the department had insufficient manpower and lacked necessary equipment to do their jobs. Despite several raises, pay hasn’t kept pace with compensation for state police, private security and law enforcement in neighboring parishes, causing the department to shed senior officers faster than it can replace them.

It’s probably going too far to claim that none of the social investments in NOLA for Life have reduced murders, according to Stephen Phillippi, a juvenile justice researcher at Louisiana State University. Midnight basketball, for example, occupies young people’s time and attention outside of school, time that might otherwise be spent getting into violent conflicts. But most of NOLA for Life’s impact probably won’t show up clearly for several more years, and even then, proving that some part of the strategy drove down crime will be difficult because the city hasn’t set up an independent evaluation. If everything goes well and murders are down, “it would be tough to say it was because of NOLA for Life,” Phillippi says. “If it goes badly, it would be tough to say it was because of NOLA for Life.”

For his part, Landrieu doesn’t seem overly concerned with proving that NOLA for Life is the reason murders dropped for three successive years. “It seems pretty obvious that when we started concentrating on it, simultaneously murders started to go down,” he says. “There seems to be something of a correlation. I don’t really want to get in a fight of whether we caused it or not -- I don’t really care. The fact is that it’s gotten lower and it’s gotten lower in a fairly dramatic fashion. Having said that, our murder rate is still way too high and we have a lot more work to do.”

There is widespread agreement that the murder rate is still disturbingly high. The city’s progress, after all, is relative. There are still more murders in New Orleans than in most cities its size. Even in 2014, when the number was at its lowest point in eight years, residents reported that they didn’t feel safer. “It’s difficult to have a perception of safety when you live in a neighborhood where gunshots are a daily occurrence,” says Lisa Fitzpatrick, executive director of APEX, a drop-in center for at-risk youth in Central City. “Residents aren’t going to drill down into the statistics.”

Fitzpatrick says she does think the city is getting safer, and she has a very specific reason. Two years ago, a gunman fired into the playground behind her youth center. Fitzpatrick ducked and retreated into the center’s bathroom, where she dialed 911. It took 45 minutes for police to respond, and the officer left the scene without finding her. In mid-March of this year, another gunman shot one of the boys who uses the youth center. The boy had reached the center’s front door, where Fitzpatrick ran out to perform first aid, and she soon saw something out of the corner of her eye. “There was this mountain of a man, standing over us,” she says. An officer had arrived less than three minutes after the shooting. “He was just there, standing between us and the corner where the shooting had happened, at great risk to himself, guarding over us.”

Fitzpatrick knows people are skeptical about whether crime is actually down and whether NOLA for Life actually works. She also knows what she’s seen firsthand. “Because of personal experience,” she says, “I feel safer now than I did two years ago.”

(Source: FBI Uniform Crime Reports, with a Governing calculation of the 2015 rate based on a population estimate from the U.S. Census.)

When murders rose in early 2015, West and his team decided to revisit their original assessment of violent crime from three years before. What they feared was that a turf war between gangs was responsible for the wave of gun deaths. Instead, they found that a new problem had cropped up. Group-involved murders continued to decline, but domestic violence incidents had increased. The city hired more detectives to work domestic violence cases and changed 911 dispatch protocols so that police would respond faster to domestic violence calls. It expanded training for officers to identify patterns of abuse before they become deadly. The police also noticed a new concentration of group-involved murders in a neighborhood that NOLA for Life hadn’t targeted, prompting the Multiagency Gang Unit and outreach workers from CeaseFire to focus more of their time on that neighborhood.

After reviewing the crime data, West’s team concluded that the homicide numbers in the first quarter of 2015 were abnormally high, and the numbers would level off over time. “A lot of what we were doing didn’t need to change,” West says. Sure enough, the second half of the year was just shy of the lowest number of murders in a six-month period since the 1970s. After a rocky start, homicides in 2015 ended about 9 percent higher than the year before, still one of the lowest murder tallies in 25 years. The lower level of violence carried over into the first two months of this year, leading The Louisiana Weekly to report in early March that the city was on pace for fewer murders than at any time since 1969. “My response was, it’s really early,” West says. “I think some amount of consistency on both sides helps. Good or bad, it’s just too short of a time frame to really judge.” Maybe West was correct to be cautious. This March saw one of the bloodiest weeks in recent memory, casting doubt on the prospects of another annual decline.

*This story has been updated to reflect the results of an analysis by the Brennan Center for Justice that was released after the May print issue of the magazine went to press.