A growing number of firms are, like Azavea, on the leading edge of corporate reforms to make American businesses better stewards of the environment and worker well-being. They are so-called benefit corporations, whose charter explicitly allows them to pursue purposes other than sheer profit. Many are also certified, meaning they’ve met strict standards set by the nonprofit B Lab. More than 2,600 certified “B Corps” operate globally, according to the group, including such well-known brands as ice cream maker Ben and Jerry’s, women’s clothier Eileen Fisher and crowdfunding platform Kickstarter.

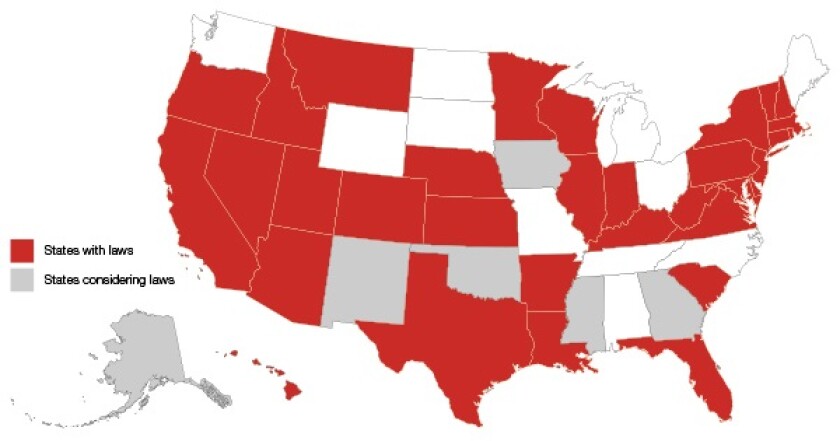

Now, an increasing number of governments are facilitating the growth of benefit companies. At least 34 states and the District of Columbia have passed laws -- most of them within the past six years -- that allow companies to organize as legally recognized benefit corporations. Legal status confers a potentially significant advantage for a company: protection from shareholder liability if executives fail to maximize profit in pursuit of other goals.

Legalizing B Corps

Thirty-four states, including the District of Columbia, have passed laws recognizing benefit corporations. Another six are currently considering such legislation.

(Source: B LAB)

One state that affords such protection is Pennsylvania, but the city of Philadelphia goes even further. It offers a tax credit of up to $8,000 for sustainable businesses -- either those certified or those that can show they meet similar standards of social and environmental responsibility. Christine Knapp, director of Philadelphia’s Office of Sustainability, said the city launched the sustainable business tax credit in 2012 on a pilot basis, limiting it to 25 companies and capping the credit at $4,000. Growing demand led to the credit’s expansion in 2015, and while the current credit is capped at 75 businesses on a first-come, first-served basis, further expansions could come when the credit is reauthorized in 2022. “We want to recognize the businesses leading by example,” she says, “but also encourage other businesses to take some action.”

Andrew and Jenn Nicholas, husband-and-wife co-founders of the graphic design firm Pixel Parlor, say the credit has been a big help to their 10-person company. “It’s a challenge to be profitable and provide benefits to our employees,” says Jenn Nicholas. “Every tiny bit helps, and it feels like somebody is looking out for us when the general climate [for small businesses] is the opposite.”

At the much bigger Azavea, the credit has had a smaller bottom-line impact. Still, says Cheetham, “symbols matter. It’s a powerful symbol when you’re going to other businesses and trying to attract them into the city.”

For state and local governments, this business-led reform is well worth encouraging. Research has shown that benefit companies are a boon for workers and their communities and could encourage a much-needed shift in national corporate culture -- away from the single-minded focus on shareholder profit. In short, benefit corporations are a refreshing countertrend that could ultimately prove more effective than prescriptive efforts to regulate corporate behavior. They prove, says Anna Shipp, executive director of Philadelphia’s Sustainable Business Network, that “an equitable society and a thriving economy are not mutually exclusive but interdependent.”

But some businesses, according to Shipp, may need a little encouragement to refocus their mission on doing good. Laws to recognize benefit corporations’ legal status is the first step, she says; following Philadelphia’s lead with a tax credit could be the next catalyst.