Five years ago, in the immediate aftermath of the Great Recession, Colorado Springs, Colo., became a poster child for municipal service cuts. Because the majority of its revenue comes from sales taxes, the city was hit hard -- and particularly early -- by the economic downturn. After its revenue plummeted in 2009, Colorado Springs slashed many core public functions in an effort to make ends meet. One-third of the city’s streetlights were turned off to save money. Swimming pools and community centers were shuttered. The city stopped collecting trash from parks and ceased mowing the grassy medians in downtown streets. Buses quit running on nights and weekends; some routes were terminated altogether. City jobs went unfilled, including firefighters, beat cops, drug investigators and other essential positions. The police department auctioned off its three helicopters online. Infrastructure spending fell to zero.

The sweeping cuts gained international attention, including a cover story in this magazine five years ago this month. But it wasn’t just the cutbacks that drew focus to Colorado Springs. It was the way citizens responded to them. In November 2009, with the looming service reductions already announced, local voters overwhelmingly turned down a proposed property tax increase. The message from residents was clear: We’d rather suffer the cuts than spend more to avoid them.

Thus the already libertarian-leaning city became an extreme experiment in limited government. “People in this city want government sticking to the fundamentals,” City Councilmember Sean Paige told Governing in 2010. “I think the citizens have made it clear that this is the government people are willing to pay for right now. So let’s make it work.”

In many ways, that’s exactly what happened. The bare-bones budget went mostly to fund fire and police services, along with some money for parks and public works. Citizens and private groups filled in the gaps. Neighborhoods chipped in to pay for their own streetlights. Churches ran some of the community centers that had been slated to close. Volunteers helped out with back-office police functions. Some outsourcing was more formal: A city-owned hospital was sold off to the University of Colorado health system, and the YMCA formally took over the public swimming pools. The city even privatized its entire fleet of vehicles.

By late 2011, things started looking up. Sales taxes began to rebound, and the city restored many of the services that had been cut. The lights came back on, trash pickup resumed, more cops were hired. By the next year, Colorado Springs’ reserve funds were at their highest levels ever, a fact that helped the city cope with a couple of devastating floods and wildfires, including the 2012 Waldo Canyon fire that killed two people and destroyed nearly 350 homes in the area. By 2013, the city’s revenue was already back to pre-recession levels.

It’s easy for Colorado Springs residents today to feel as if the city has fully recovered from the recession. “There’s this sense that everything’s back to normal,” says Daphne Greenwood, an economics professor at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs. “But just like the rest of the country, we’re not really back to where we were.”

What’s happened in Colorado Springs has played out in municipalities across the country. Revenues are back up and jobs are returning. Many cities, in fact, are thriving. But there are worrisome cracks in the foundation -- structural imbalances that go beyond the cyclical churn of the economy. “Compared to 2010, obviously cities are much better off -- at least in the short term,” says Kim Rueben, a senior fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center who focuses on state and local economies. “But there are still fundamental problems. Things are getting better, but I wouldn’t necessarily say it’s all sunshine and roses. This is really just a time for people to catch their breath.”

Nationwide there’s a lot to be optimistic about when it comes to local government finances. Property values, after bottoming out in 2012 and 2013, have bounced back. The National League of Cities’ (NLC) most recent City Fiscal Conditions report, published last fall, showed that property tax collection was at 90 percent of pre-recession levels, and NLC economists say they expect to see higher numbers in next month’s report. Just in the past year, it seems cities have turned a corner. That 2014 NLC report showed the first positive growth for city revenues in five years, and for the first time since the downturn, a majority of local officials surveyed in the report said they were optimistic about their cities’ fiscal health.

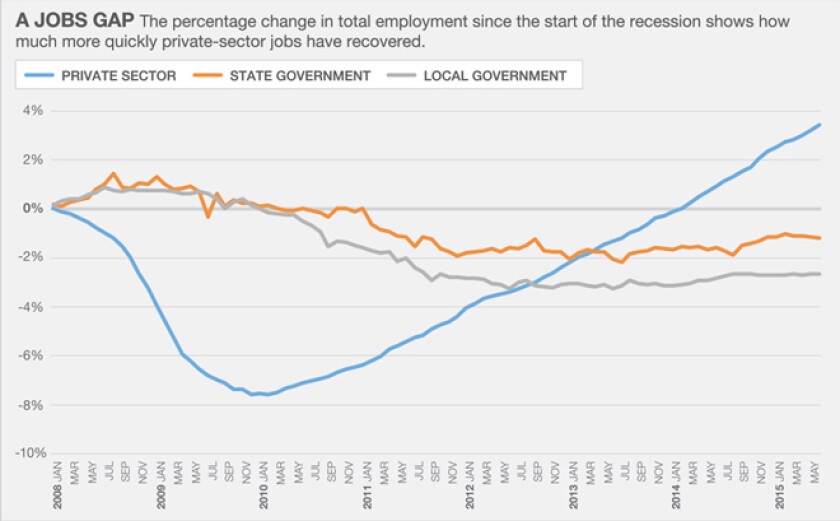

There are other positive indicators. Last year, more cities increased the size of their municipal workforce than decreased it, something that hasn’t happened since 2008. In fact, this past May marked six consecutive months of job growth for cities -- a first in several years. And in the first quarter of 2015, Moody’s credit rating upgrades for cities finally outpaced downgrades.

But every silver lining has a cloud. Take the employment numbers. Despite those six months of sustained growth, cities are still about 195,000 jobs below the peak employment levels they saw at the end of 2008.

Or consider the Moody’s upgrades. It’s an important sign, says Tom Kozlik, an expert on local finances and a municipal strategist with PNC Bank. “On the other hand, it took several years for that to happen, and there are still a number of downgrades happening.” Many of those downgrades are occurring because of multiyear fiscal structural imbalances. Lots of municipalities are still dipping into their reserves as a way to balance the budget year to year. “That tells me it’s going to be really difficult to turn this trend around,” says Kozlik. “If local governments don’t really sit down and recognize this new financial reality -- budgeting conservatively and managing expenditures -- then their credit will deteriorate and they’ll continue to face downgrades.”

Overall the recovery has been markedly uneven for localities. An NLC report released in late July laid out some of the frustrating inequalities of “an economy defined as much by job gains as by slow productivity growth, suppressed wages and stubborn unemployment.” In the report, which surveyed more than 250 municipal officials from across the country, nearly all cities reported a rosier economic picture, with 28 percent reporting a “vast improvement’ in their economy and 64 percent citing a “slight improvement.” But smaller cities of under 100,000 residents haven’t seen the same rates of economic growth that larger cities have, and some of those smaller localities actually reported worsening conditions over the past year. Rising demands in all cities for assistance in areas such as food and housing indicate that not everyone has shared in the strengthening economy. “Even those cities that are emerging as post-recession leaders still have a long way to go in terms of low- and middle-class residents,” says Christiana McFarland, co-author of the NLC report. “You see conflicting storylines within the same city.”

The recovery has been a mixed bag in Colorado Springs as well. On the one hand, revenues are at 10-year highs. But the city’s population has also risen, meaning per-capita revenue and expenditures have actually fallen sharply since 2007. And while police and fire positions have almost inched back up to where they were before the downturn, other departments are still stretched thin. The number of nonemergency civilian positions is down 24 percent today compared to 2008. “Of course we’re in a better place now than we were,” says Kara Skinner, the city’s chief financial officer. “But we’re still super, super lean.” City departments like parks and public works want to add back some of the staff they’ve lost, she says, “but the funds are just not there to meet those requests. Realistically that’s just a new normal for us.”

Drive around Colorado Springs today and there’s one thing you can’t help but notice: “Potholes,” says Greenwood, the economics professor. “It’s hard to keep your eye on traffic because of having to dodge all the potholes.” Colorado Springs is spread out over 195 square miles, with 5,600 miles of roads, and most of them are in disrepair. Sixty percent of the city’s roadways have gone more than a decade without being repaved, and the pothole problem has become severe. The city’s roads are “rapidly deteriorating, and we need to deal with it,” says Mayor John Suthers, who took office this June. “That’s definitely a product of the recession. There’s still essentially no money for road improvement or maintenance.”

Suthers is backing a slight increase in sales taxes for five years, which would give the city about $50 million a year solely to fix its roads. Residents will vote on the proposal in November. Suthers says he’s “incredibly optimistic” that it will pass, despite the strong antitax sentiment in his city. Residents, he says, are keenly aware of the poor state of the city’s roadways.

Infrastructure investment is not a problem unique to Colorado Springs, of course. During the recession, one of the first places cities reduced their spending was on the maintenance of roads and bridges and other facilities. Most haven’t restored that funding even now. But as the nation’s infrastructure continues to deteriorate, localities will have no choice but to spend money to repair it. As early as next year, “growing capital demands will force local governments to significantly increase investment in infrastructure,” one Moody’s analyst said in a report earlier this year.

“Cities are disinvesting -- you’re not even maintaining the value of the infrastructure you have,” says Michael Pagano, dean of the College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois at Chicago and co-author of NLC’s City Fiscal Conditions report since 1991. “We’ve postponed repair and maintenance for so long that we’ve now got to decide what to address, what to abandon and what to sell off.” Public-private partnerships are one way to help finance projects, and cities are increasingly utilizing them as an important tool. But many of cities’ most pressing infrastructure needs -- alleys, sidewalks, school facilities and bridge maintenance -- might not be attractive to corporate partners.

If infrastructure is one looming crisis for localities, the other is certainly pensions. While a few cities have initiated some retirement benefit reforms in the past five years -- around 20 percent of localities, according to NLC -- pensions remain a major fiscal problem for municipalities. Pension burdens increased for 31 of the 50 largest local governments in fiscal 2013, the most recent year for which data is available, according to a recent Moody’s report. And in general, required pension contributions are growing faster -- in some cases much faster -- than local government revenues. As aging public employees retire in the next decade, those pension obligations will continue to gobble up an increasing share of city expenditures, crowding out spending on other services.

The twin crises of infrastructure investment and pension burdens represent deeper structural problems that cities must confront. The good news, says Pagano, is that cities are at least talking about their pension and infrastructure needs. But talk doesn’t always translate into appropriate action. “Yes, cities are having serious conversations” about these topics, he says. “But are they adequately addressing the long-term liability issue? That’s something we don’t have an answer to yet.”

The underlying question, in Colorado Springs and elsewhere, is whether cities are any better equipped to handle the next fiscal downturn. If history is any guide, an economic contraction will happen within a few years. Are cities ready? In one aspect, they may be. “If the Great Recession taught cities anything,” says Pagano, “it taught them not to believe in overly optimistic forecasts in their pension systems. Maybe that’s a good thing.”

In Colorado Springs, leaders say they’re definitely better prepared. The city’s reserves today are $10 million higher than they were in 2007. And Suthers says that if voters pass his tax increase for road repairs, the city will be on even surer footing. “We’re in a better place than we were,” he says. While Suthers doesn’t question the cuts that were made in 2010 because they were “philosophically consistent” with the views of Colorado Springs residents, he acknowledges that they remain an issue. “I’m still dealing with many of the cuts we made five years ago and trying to get back to square one.”

For the most part, though, cities continue to face those entrenched, longer-term trends that will make it much harder to weather future fiscal storms. In addition to unmet infrastructure and pension needs, cities are bridled with an increasingly outdated sales tax system that doesn’t reflect the shift to a service economy. “I had hoped the Great Recession would cause cities to really examine the adequacy of their fiscal architecture,” says Pagano. “But for the most part, that hasn’t happened.”

Without some sort of action on taxes, infrastructure and pensions, he says, cities won’t be able to withstand the next downturn any better than the last. “I’m not sure they’re any more prepared for a recession in the next five to seven years than they were in 2008,” Pagano says. “The future isn’t going to be too much different from the past.”