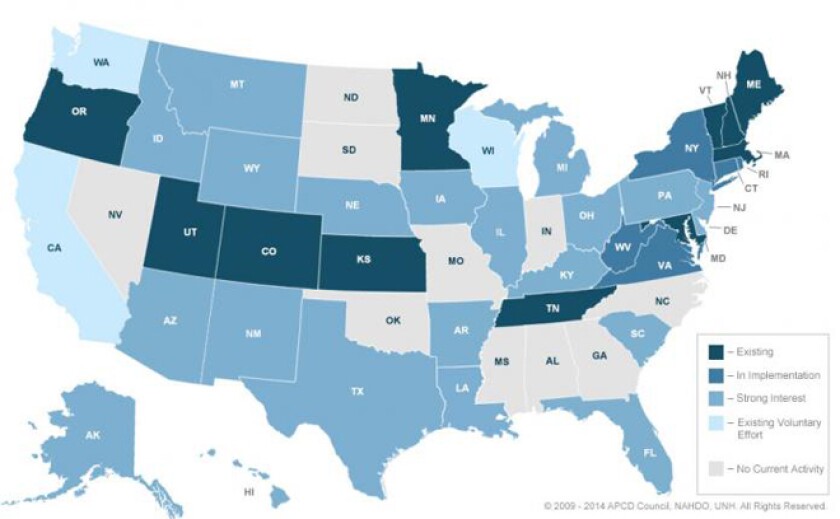

At this point, 11 states have what are called all-payer claims databases (APCD), five are currently implementing an APCD and another 21 states have shown a "strong interest" in creating one, according to the All-Payer Claims Database Council, a group of government, private and academic players that provide expertise on the subject. New Jersey was the first state to file legislation in 2014 to authorize one.

“The more states implement them, the more the others [will] follow suit,” said Denise Love, executive director of the National Association of Health Data Organizations.

All-payer claims databases predate the Affordable Care Act, but the federal health law has intensified the interest in data about state health costs, and databases can help states evaluate the impact of new health pilot projects, concluded the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation in a recent report.

“Overall, states with APCDs have a clearer baseline from which to evaluate the impact of reform efforts and to understand the health of and health care provided to their citizens,” the influential health policy foundation wrote.

This appears in our free Health e-newsletter. Not a subscriber? Click here.

Voluntary databases exist in three states, but the rest of the participating states have legislation that mandates commercial insurers to report information. The data typically includes information about demographics, costs, diagnoses, providers and procedures performed and has a generic tracking number in place of a patient’s name.

The broader purpose of APCDs is to inform and guide public policy, but uses have varied. Some states have focused on providing cost information online for consumers; some have studied why costs and utilization vary by region; and some have used the database to design or evaluate reforms.

The costs of running one can be the biggest barrier: Annual expenses span about $500,000 to $1 million or more, depending on the number of functions a system is performing, the size of a state’s health-care system and the number of commercial insurers, according to Love.

New Hampshire, an early APCD adopter in 2005, operates one of the cheaper databases. The state reports on how much doctors charge and how much discounts providers give insurance companies, which has allowed consumers to make more informed decisions and allowed providers to adjust their rates to better position themselves in the market -- whether that means raising or dropping prices.

“We’ve heard from health-care providers who want information to put their rates more in line with the market,” said Tyler Brannen, a health policy analyst at the New Hampshire Insurance Department. “They don’t want to be seen as an outlier. Certainly there are some who are shooting to be the low-cost providers and are showing data to support that.”

But New Hampshire's use of APCDs doesn't stop there. The state has used the data to answer long-standing questions, like whether doctors raise rates for commercial payers to make up for Medicare and Medicaid shortfalls (They don’t, at least not in New Hampshire); to calculate before and after costs for participants in a coordinated care project across nine primary care practices; and is currently using claims data to guide budgeting for five accountable care models across the state. Accountable care organizations band doctors together and pay them one lump sum per patient, encouraging them to keep costs down by allowing them to keep a portion of money saved.

Minnesota, which implemented its system in 2009, is currently finalizing a comprehensive report on the costs and quality of care from providers and preparing it for public release. While that’s going on, they’re also determining whether they can use the data to adjust for risk in the state’s health care exchange pools, much like the federal government will do to avoid premium spikes from an overabundance of more costly patients. (Massachusetts, which served as a model for the federal health-care reform law, already does this.) Minnesota is also trying to decide whether the claims data could be used by its insurance department to review the rates it allows carriers to charge.

“We’re seeing how that data can be useful in the process of rate review, background analysis, to sort of build a Minnesota-based actuarial calculator,” said Stefan Gildemeister, director of health economics for the state.

All of those initiatives have been years in the making, underscoring perhaps the chief barrier to creating an all-payer claims database: finding the political will to cajole the lobbyists of commercial insurers and to authorize upward of $1 million a year for a tool that will take time to develop.

“It’s really hard to say to a state, ‘You really need to build this database because it will be useful to you in five years,’” Love said. “But those states that have a vision know if they build it today, they’ll have some valuable information that really forms a foundation for what’s to come.”