Medicaid accounts for 15.7 percent of state general fund spending. But cutting Medicaid spending is notoriously tricky. One obstacle has been the “maintenance of effort” requirements included in ARRA and extended by the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The provision prohibits states, with limited exceptions, from changing eligibility standards to reduce the number of Medicaid beneficiaries. That’s led states to turn to other tactics.

Some are familiar, such as cutting payments to providers, scaling back dental benefits and restricting access to brand-name prescription drugs. Some are controversial, such as capping medical malpractice jury awards. Another -- beefing up anti-fraud efforts -- is fast emerging as one of the highest return-on-investment initiatives states can undertake. Still, some of the most interesting initiatives are just now taking shape. Oregon enacted legislation that will move more than 500,000 Oregonians into new coordinated care networks that will emphasize prevention and primary care. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts has responded to state demands to contain costs by creating a new global payment system, the alternative quality management contract. Policymakers in Vermont are instituting a single-payer system -- the most radical change of all. “If we are really going to grow jobs and opportunities,” Vermont Gov. Peter Shumlin argues, “we have to deal with health-care costs.”

From the most common to the innovative, here are five approaches states are trying, along with assessments of their prospects for success.

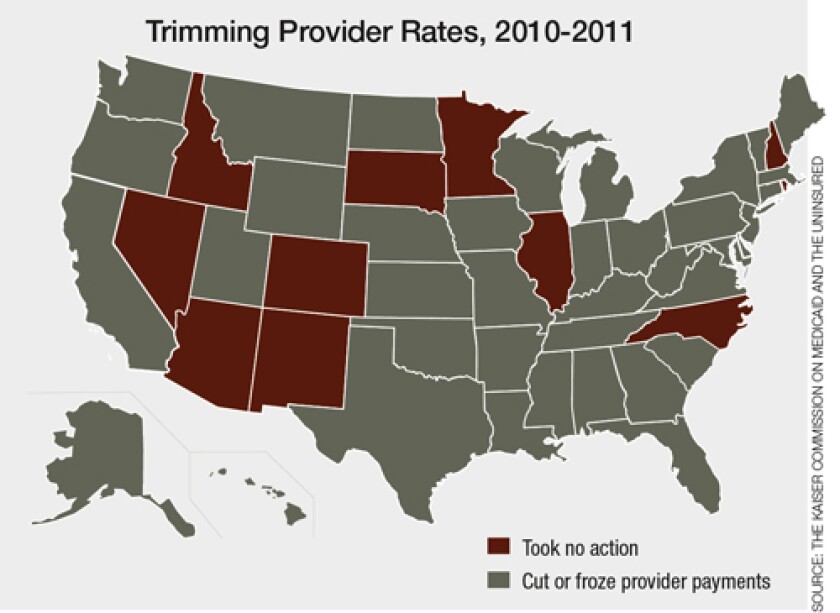

1. The Kindest Cut: Reducing Provider Payment Rates and Patient Benefits

*Idaho is shown here as having not cut provider rates. However, the state has reduced payments, froze rates and curtailed

benefits in the past three years, according to the Idaho Department of Health & Welfare.

In 2008, Medicaid fee-for-service provider payments averaged only 66 percent of Medicare rates (which in turn are lower than commercial reimbursement rates). Only five states pay Medicaid providers at even the Medicare standard. (The ACA will change that. It requires state Medicaid programs to reimburse certain primary care providers at Medicare rates by 2014.)

Providers have long alleged that cutting their payment rates doesn’t actually save money. Rather, it shifts costs. According to this argument, doctors and hospitals pass cost increases along to private health insurers. Insurers pass them on to employers, who respond by increasing premiums for employees and holding down wage increases.

Providers have also argued that cutting reimbursement rates makes it more difficult for Medicaid beneficiaries to find providers. At first glance, the statistics appear to bear them out. According to a 2008 Health Systems Change survey, only 53 percent of physicians were accepting new Medicaid patients. In comparison, 74 percent of practices said they took “all or most” new Medicare patients, and 87 percent reported accepting all or most new private insurance patients.

Researchers say matters aren’t so clear cut. “There is a lot of negative press and rhetoric tying access to payment in the Medicaid program,” notes Robin Rudowitz, a policy analyst with the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. “Data and research really show that access in Medicaid is pretty comparable to access for private insurance for similarly situated individuals, particularly when you look at primary and preventative care.” In other words, the access problems that Medicaid beneficiaries experience don’t result so much from Medicaid’s policies or reimbursements as from the problems that all low-income people experience in trying to connect with providers who are often located elsewhere.

The evidence for cost-shifting isn’t clear cut either. In its report to Congress earlier this year, MedPAC, the advisory federal panel for Medicare, took a look at the issue. It found that most hospitals reacted to reimbursement pressure by operating more efficiently.

In short, cutting provider reimbursements can save money (though states must comply with broad federal standards). Cutting supplemental benefits, however, may be riskier. Researchers recently looked at the result of Oregon’s decision to eliminate Medicaid dental benefits back in 2003. They found people who lost benefits responded by seeking care in more expensive emergency room settings. “Cutting benefits to save money is not easy,” says Rudowitz.

2. The Bad Guys: Cracking Down on Fraud and Abuse

Six years ago, the Institute of Medicine estimated that between 30 to 40 percent of all health-care spending was “misspent.” Most of that “misspending” went to inappropriate care, but a significant amount was lost to fraud and abuse -- somewhere between 3 and 10 percent of total health-care spending. Not surprisingly, Medicaid has become a priority for fraud fighters.

The stakes are enormous. A 2008 report from Florida’s Office of Program Policy Analysis and Government Accountability, a research unit of the Florida Legislature, estimated Medicaid fraud costs to the state at between $940 million and $3.7 billion per year -- 5 to 20 percent of the state’s total Medicaid spending.

“With health and human services consuming more and more of the state budget, getting waste, fraud and abuse out of the system is more important than ever,” says Texas First Assistant Attorney General Daniel Hodge.

States such as California, Florida, New York, Ohio and Texas have responded aggressively. By adding 10 new staff positions to its Medicaid Fraud Control Unit, Ohio increased its recoveries from $65 million in 2008 to $91 million in 2009. In recent years, Texas has beefed up its Medicaid integrity effort, creating a separate civil fraud division in fiscal 2008-2009. According to Hodge, the new office, which has funding for 41 employees and a yearly budget of about $6 million, returned $96.5 million to state and federal taxpayers in fiscal 2010. That’s quite a return on investment. Not surprisingly, the National Association of State Budget Officers reports that some 20 states announced plans to ramp up Medicaid integrity activities this year. In addition, state Medicaid fraud units are teaming up to mount complex, multistate cases, many targeting pharmaceutical companies promoting unapproved, off-label prescription drug use, a strategy that in 2008 alone recovered $1.4 billion from 13 multistate civil suits.

The federal government has joined the effort too. In 2005, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) created the Medicaid Integrity Program and gave it a very specific charge: Provide state Medicaid programs with the technical assistance, such as sophisticated data mining, to identify overpayments. Earlier this summer, CMS began using predictive modeling to target Medicare fraud in south Florida. Medicaid databases are far more complicated, but several states have shown how powerful they can be in finding fraud and recovering funds.

Perhaps the most innovative state has been New York. After reports of massive fraud surfaced in 2005, the state created the nation’s first Medicaid inspector general (IG). Taking advantage of New York’s robust Medicaid database, auditors from IG James Sheehan’s office and staff from the state’s Medicaid program teamed up to identify the outliers -- the providers whose billing practices clearly stood outside the norm -- and went after them. Sheehan’s aggressive tactics have attracted critics. They’ve also generated results. In 2007, New York recovered $130 million. In fiscal 2008-2009, recoveries jumped to $304 million, while the state Medicaid Fraud Control Unit brought in another $227 million, bringing the total funds recovered by the state to more than $550 million. This was 1.2 percent of New York’s total Medicaid expenditures, the highest recovery rate in the nation. In contrast, CMS figures show that the average state recovers a mere 0.09 percent of state Medicaid spending. No wonder at least half a dozen states -- Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky and New Mexico -- followed suit in creating inspectors general.

3. The Tort Toll: Capping Jury Awards in Medical Malpractice Suits

Last fall, Peter Orszag, President Obama’s first Office of Management and Budget director, penned a column for The New York Times in which he identified several regrets about the course of health-care reform. Atop his list of missed opportunities was medical malpractice reform. “Too many doctors,” Orszag wrote, “order unnecessary tests and treatments only because they believe it will protect them from a lawsuit.”

It’s called “defensive medicine,” and according to physicians, it’s a major driver of rising health-care costs. A much-cited 2006 study conducted by PricewaterhouseCoopers for America’s Health Insurance Plans, the nation’s health insurance trade association, estimated that the practice of defensive medicine increased total health expenditures by about 10 percent. Studies of this sort have spurred states to take action. More than two dozen now have laws designed to limit or cap jury awards in medical malpractice cases. Some economists have suggested that such legislation has reduced state health-care expenditures by 3 to 4 percent.

However, attempts to cap jury awards in medical malpractice cases remain intensely controversial in states with powerful plaintiffs’ bars. Earlier this year, lawmakers in Albany offered Gov. Andrew Cuomo a rare rebuke by rejecting his efforts to cap awards in New York, a step that New York hospitals (pointing to a 2004 study commissioned by malpractice insurers) claimed would have allowed them to reduce their premiums by a quarter.

Did New York miss a chance to dramatically cut premiums? Probably not. According to University of Southern California professor Darius Lakdawalla, the most recent research simply doesn’t support projections of big savings. Certain professions (notably cardiologists and obstetricians) do seem to engage in the practice of defensive medicine, says Lakdawalla. However, in a recent National Bureau of Economic Research paper, Lakdawalla found that reducing malpractice awards further would have only a modest impact on total health-care expenditures.

“A 10 percent reduction in malpractice costs would reduce total health-care expenditures by, at most, 1.2 percent,” says Lakdawalla. That’s a much smaller percentage reduction than an earlier generation of studies predicted. However, given overall national health expenditures of $2.6 trillion, it would still translate into big savings. But that reduction would come at a price -- higher mortality. Precisely because some doctors practice defensive medicine, higher malpractice costs are likely to save lives, which more than justifies the impact on medical costs.

That doesn’t mean states shouldn’t act in this area. Orszag has suggested one interesting idea: Instead of capping awards, states should pass laws that provide “safe harbor” for physicians who practice evidence-based medicine. (Current estimates suggest that only about 50 percent do.) Fred Hellinger and the authors of a recent American Journal of Public Health article suggested another approach. Noting that the majority of costs are incurred in resolving and paying for claims, “a higher-value target for reform than discouraging claims that do not belong in the system would be streamlining the processing of claims that do belong.” New York’s judge-directed negotiation approach, under which judges encourage plaintiff and defense attorneys to settle, is one such approach.

States are also exploring ways to reduce errors that don’t involve the legal system. A particular focus has been re-hospitalizations and what is known as “potentially avoidable events.” One year ago, Maryland set out to reduce the rates of occurrence of 49 “adverse” events. The state, which has the nation’s only all-payer rate setting system, decided to pay hospitals that did a better-than-average job of reducing such incidences a bit more. Hospitals that did worse got less. One year in, the state has seen a 20 percent decline in hospital-acquired infections and $60 million in savings.

4. Services United: Managing Care for the Chronically Ill

Five percent of Medicaid beneficiaries account for up to 50 percent of total Medicaid spending. More than 80 percent of these high-cost beneficiaries have three or more chronic conditions, and up to 60 percent have five or more. Yet the majority of these patients receive fragmented and uncoordinated care, often leading to unnecessary and costly hospitalizations and institutionalizations.

That is beginning to change. More than half the states are currently attempting to align incentives with a patient-centered medical home -- a form of care that replaces episodic treatment based on individual illnesses with a long-term coordinated approach. States have high hopes that big savings will result from the move toward medical homes. In 2009, West Virginia estimated that a medical home initiative involving 1,800 physicians would produce annual savings of $57 million for the state, as well as savings of $173 million for insurers and $171 million for policyholders. But so far, efforts to evaluate these medical homes and other coordinated care initiatives have been distinctly tentative in their findings. In the July issue of Health Affairs, Mary Takach, program director for the National Academy for State Health Policy, characterized the early evidence of such programs as “promising.” She noted that in several state programs, medical-home initiatives had resulted in declines in per capita costs for patients and increased participation by physicians in Medicaid. That said, she noted that “the patient-centered medical-home model is very young and has only recently been implemented in mainstream practices.”

Another popular strategy is pay-for-performance systems, which reward health-care plans and providers for meeting or exceeding pre-established benchmarks for quality of care, health results and/or efficiency. By the end of this year, 85 percent of state Medicaid programs will have instituted some kind of pay-for-performance program. Most programs come in one of two flavors. The first emphasizes case management. Perhaps the most notable example of this approach is North Carolina’s Community Care program, in which 14 networks serve more than 1 million Medicaid patients. Each network has a small cadre of caseworkers who help manage care for people with multiple, chronic syndromes. Providers are paid a small monthly stipend to coordinate care. The outcome, state officials say, has been better care and an 8 percent reduction in the rate of growth of Medicaid spending.

The second type of pay-for-performance plan takes place within the context of managed care. More than 70 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries are already enrolled in some form of Medicaid managed care plans, and states as diverse as Kentucky, Florida and New York are pushing ahead with plans to expand these programs even further. That has some experts worried. “The idea of putting your entire long-term care program into managed care is a radical one,” says Joan Alker, co-director of Georgetown University Health Policy Institute’s Center for Children and Families. “Managed care done well, obviously, is a good thing, but there are particular risks involved when you’re talking about people with a lot of health-care needs. When [a shift to] managed care like this is done with a budget cutting motive, there is a concern about moving too rapidly in this direction.”

One area of coordination on which virtually every health-care expert agrees is promising care for the dual eligible -- people who are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid. There are 9 million people who fall into this category -- 15 percent of total Medicaid enrollees. Nonetheless, this small group accounts for 39 percent of total Medicaid spending. Yet according to Melanie Bella, a former Indiana Medicaid director who now heads the Federal Coordinated Health Care Office at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, only about 100,000 people out of this population “are in what I’d describe as truly integrated care.”

Bella’s office is working to change that. In April, CMS selected 15 states with whom it would work to design care-coordination initiatives. One approach Bella intends to explore would encourage the CMS, states and health plans to enter into a three-way contract. Participating plans would receive a blended payment in exchange for providing comprehensive, seamless coverage.

However, some states worry that blended payments could become a way to cut funding. “If the blended rate … is intended to do some good things for the states for us to administer at the ground level, we’d like to have that conversation," Washington Gov. Christine Gregoire, the head of the National Governors Association, told Kaiser Health News. “If on the other hand it’s code for dramatic cuts, that’s a different subject. And, unfortunately, that’s what most of the governors believe that it is.”

5. Going Global: Reforming the Delivery System

It’s easy to see the American primary-care health-care system as broken -- “the victim of underinvestment, misaligned incentives, and malign neglect,” as Health Affairs editor Susan Dentzer once wrote. For many in the health field, addressing the problems most commonly associated with our health-care system means changing the system itself, moving away from uncoordinated fee-for-service payment systems that reward volume toward capitated arrangements that reward value. Despite the current revenue crunch, it’s a process states are already beginning.

Twenty states are currently pursuing plans to change the health-care delivery system. One of the most notable is Massachusetts. Five years ago, it enacted the nation’s most ambitious health insurance coverage expansion since Hawaii’s decision in 1974 to require all employers to provide health insurance. The Massachusetts model, with its subsidies for low-income residents and a health exchange for small businesses and individuals, became the model for the Affordable Care Act. Now the state is trying to reform health delivery so the costs of health care won’t swamp its system. The centerpiece of this effort has been a pay-for-performance reimbursement system proposed by the state’s largest insurer: the alternative quality contract.

The arrangement works in the following fashion. Participating doctors and hospitals enter into five-year global budget contracts with Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) of Massachusetts whereby they are paid a lump sum to cover all of their patients’ health-care needs -- inpatient and outpatient care, rehabilitation and prescription drugs. Providers who exceed their budgets pay the cost overruns; providers who come in under budget share in the savings. Providers who meet quality-of-care standards specified by the insurer also become eligible for performance bonuses of up to 10 percent, a much larger sum than in most pay-for-performance arrangements. Finally, BCBS works closely with providers to offer feedback on quality and efficiency. According to a year-one evaluation conducted by BCBS, participating providers saw measures of process improvements increase at three times the rate of non-participating physicians -- a rate of improvement in quality of care greater than any one-year change seen previously in the insurance provider network. A New England Journal of Medicine assessment also found modest cost savings of 1.9 percent.

Oregon is moving in a similar direction. In June, Gov. John Kitzhaber, a physician serving his third term as governor, and the Legislature passed the Oregon Health Transformation Act, which will move half a million Oregonians away from managed care and into coordinated care organizations (CCO). Four working groups appointed by the governor are working on guidelines that will establish how the CCOs will operate, who will pay for which procedure and how effectiveness will be measured. The committees will also take on the challenging question of designing a long-term care system. “We have the opportunity to do something that no other state has done, and something that has eluded our nation for decades,” Kitzhaber said in June. “That is creating a system that actually improves the health of the population at a cost we can afford.”

Finally, there’s Vermont. While states such as Massachusetts have tried to work through the private sector by pressuring insurers or through public levers by using the power of Medicaid and state purchasing to affect the health-care system, Vermont is focused more on providers. Lawmakers there are betting that the greater efficiency of a single-payer system will generate big savings. But if it doesn’t, the state has also authorized a more forceful command and control approach to cost reduction. When the Vermont Legislature committed the state to implementing a single-payer system, it also created the Green Mountain Care Board, which will have the power to do everything from setting fee-for-service rates to developing new payment models to implementing a global budget for health-care spending. Its goal, says Shumlin, is to “design the first cost containment system in America that works.”

To Shumlin, it isn’t a choice. It’s a necessity. By 2015, at current rates of growth, he says that every Vermonter will have to spend an additional $2,500 every year on health care -- even though they will be earning the same money they earned 10 years ago. And that, he adds, “makes it very difficult for us to compete with other countries who do not carry this burden.”