Within just a few blocks on Wabash, I could sample the delights of a well-stocked music store, browse a world-class bookshop, check out the merchandise in the immense Marshall Field department store, or order a Pittsburger, said to be the city's best hamburger, in the basement of the Pittsfield office building.

"The L," as the transit system is known to every Chicagoan, was a giant, noisy thing that turned Wabash into a corridor of sun-blocked semi-darkness most of the time, and it sometimes deposited pigeon droppings on the unwary pedestrian. But none of this bothered me at all — I thought Wabash was a fantastic street full of vitality and even mystery. If I got tired of walking, I could board one of the trains for a quarter and ride as long as I wanted through the Loop that the L tracks created, peeking into second-story windows that offered a wide variety of intriguing visions.

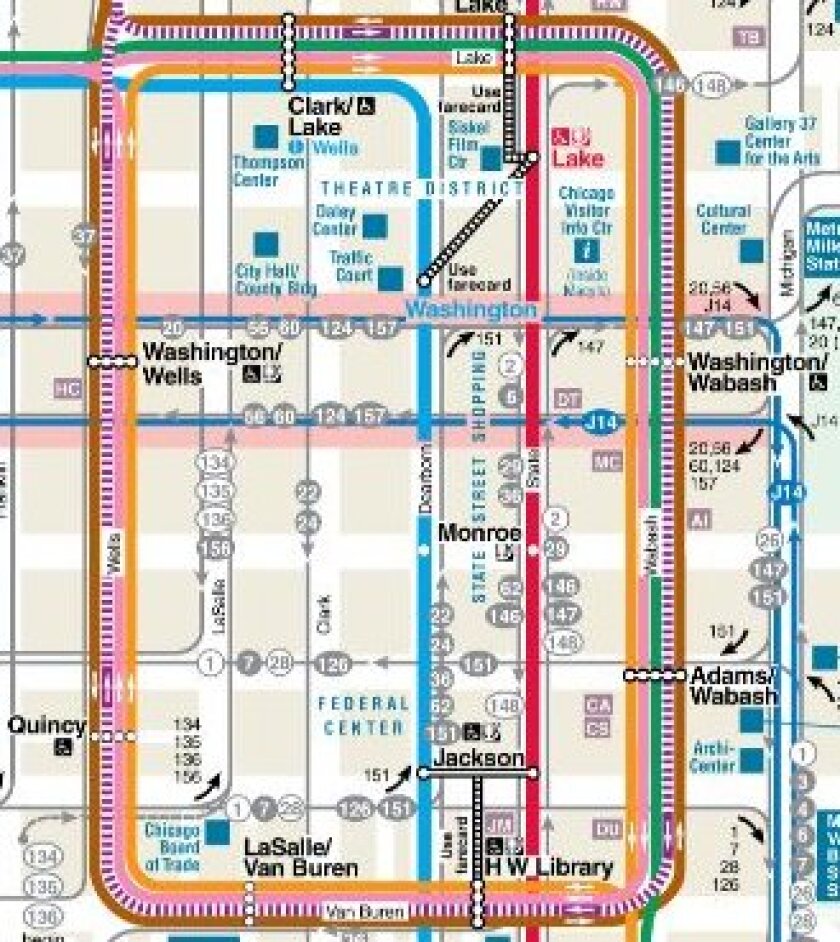

The Loop is a 2.1-mile structure that bends through and around 39 blocks of downtown Chicago, the core of a system that now sprawls many miles in all directions, and ever since it came into existence in 1895 riders and writers have looked for ways to express their fascination. "A steel skeleton," essayist Patrick T. Reardon recounts, "that because of the lumbering thunder of the trains and the squealing of their steel wheels on the turns seemed alive, like a prehistoric monster."

|

|

| A Chicago Transit Authority map of the Loop |

AND YET, AS REARDON MAKES CLEAR, for all the pride and civic boosterism, there has always been a sizeable cadre of Chicagoans who have hated the Loop and wished to see the tracks torn down. This was true right from the start. In 1894, before the trains had even begun running, a renowned railway engineer complained that the Loop's massive structure, "with its noise and jar, its midnight at noontime under it, and above all its supporting columns, cutting off nearly two-thirds of the roadways, is a tremendous and all-pervading nuisance." Seventeen years later, when the Loop system was in full and robust operation, the journalist and critic Julian Street wrote that "the business and shopping district of Chicago is at present strangled by the elevated railroad loop, which bounds the center of the city."

Criticism of the L and the Loop was fueled in part by the owners of businesses that lay outside the rectangle, jealous that they were not getting the benefits of the increased property values that existed within it. The drumbeat of criticism never disappeared, but for decades it was treated by most Chicagoans as sour grapes.

But in the second half of the last century there were two systematic assaults on the system that nearly brought it crashing down. In 1954, Mayor Martin Kennelly and a consortium of corporate magnates and real estate developers conceived what they called "The Dearborn Project," a massive new development that would create a brand-new civic center on 150 underused acres north of downtown, housing the city government, apartment towers for 5,000 residents and a huge new university campus. That plan collapsed when the incoming mayor, Richard J. Daley, pointedly asked whether "we are going to discommode the people of Chicago for a real estate promotion."

Two decades later, however, Daley changed his mind, influenced by an obvious decline in the Loop's commercial attractiveness and economic return, and the emergence of Michigan Avenue, a mile north, as the city's high-end retail corridor. He accepted the arguments of a broader business alliance that the L was an economic drag on the city and declared that the whole edifice should be torn down at once and replaced by a new subway, freeing the Loop for more lucrative development and doing away with the noise and blocked sunlight that remained the system's trademark. Daley got his way on most development issues, and he would have won on this one too had he not died suddenly in November of 1976.

Planning for the demolition continued for two more years, until another mayor, the preservation-minded Jane Byrne, appointed a commission whose recommendation was that the L should be not only maintained but modernized and improved. So the L and the Loop are still there, a century and a quarter after their debut, an outpost of solidity in a disorienting pandemic moment. The primary denizens of the Loop are now more likely to be students and tourists than the shoppers and merchants of an earlier day, but the steel-and-wood rectangle of train tracks has survived intact.

THOSE WHO FIND THE L AND THE LOOP a precious landmark, not a nuisance, nearly always declare that it is the "center" or the "heart" of the city, a physically imposing if politically fragile entity that saved Chicago from the fate of less-fortunate rival cities. But why is it important for a city to have a center? And how exactly does the L make Chicago different from other big cities?

Jane Jacobs, for one, was a staunch believer in the importance of urban centers. "Without a strong, inclusive central heart," she wrote in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, "a city tends to become a collection of interests isolated from each other."

To a great extent, that was what Chicago was before the L: a collection of isolated sections and interests. The city had a South Side, a West Side and a North Side, separated from each other by the various branches of the Chicago River, rarely interacting physically and distant enough from each other to harbor intense and sometimes dangerous rivalries. The L changed that. People from all over the city began to come together within the confines of the Loop. About all that remains of the ancient feuds is the disdain that North Side Cubs fans have for the South Side White Sox, and vice versa. Those don't nurture violence.

One thinks immediately of Philadelphia and the sometimes vicious feuds that have long existed between its parochial neighborhoods, often located within a mile or two of each other. I'm not insisting that a Chicago-style Loop would have prevented this — but well, who knows?

The truth is that no major American city has a tangible unifying enclave anything like the Loop. Cleveland has its Terminal Tower, St. Louis its Gateway Arch, Detroit its Cadillac Square, but they are not the same. In the last half-century, all of these cities saw their downtowns essentially fall apart, while Chicago, despite some rough patches, saw its downtown survive and eventually come to thrive again. Is that because of the Loop? Patrick Reardon thinks it is.

The Loop is a 2.1-mile structure that bends through and around 39 blocks of downtown Chicago. (Kidd)

WHAT'S INDISPUTABLE is that in the last couple of decades, American cities that had no real centers at all have striven mightily to create them. Houston, Phoenix and even the notoriously dispersed Los Angeles have spent billions of dollars building stadiums, light rail lines, cultural districts, commercial developments and residential complexes for the express purpose of creating a central focus. Some have had tangible success — but not to the point of establishing anything like the compact 39-block rectangle that Chicagoans have long regarded as the heart of their metropolis.

Political leaders in Phoenix began to crave a new downtown after some of the city's most prominent corporations decamped their headquarters to places perceived to have more of an identifiable center. "The common element of great cities," Phoenix Mayor Phil Gordon warned in 2009, "has always been a belief in the central core as the heart." And Phoenix has followed through, bringing large portions of Arizona State University to a new downtown campus and doing everything possible to attract a sizeable central-city residential population. It's an impressive feat in many ways. But no matter how well it does in future years, central Phoenix will never resemble the much-loved ugly duckling that has defined downtown Chicago since 1895.

In a more general sense, Reardon's story serves as a reminder of something that urban experts have often tended to miss: Cities are creatures of public policy, not simply organic entities brought together by circumstance or blind market forces. They are made and sustained by decisions of government — and in many cases, as in Chicago, decisions about transportation. The decision to build the Brooklyn Bridge made New York into an unbreakable fusion of Manhattan and Brooklyn, not an uneasy arrangement of two rivalrous cities. The way most of our metro areas function (in some cases disastrously) is the result of the decision by the federal government in the 1950s to build the Interstate Highway System and to bring it into the heart of city centers. Those weren't accidents or concomitants of inevitable urban growth. They were things that political leaders wanted to create. So was the Loop.

A couple of decades ago, my Governing colleague Alex Marshall made this point persuasively in his book How Cities Work. "Different transportation systems produce different types of cities and the places within them," Alex wrote, "as effortlessly as different types of soils produce different sorts of shrubbery, flowers and trees." It's a lovely way to say something that we often forget at our peril.