In Brief:

In 2016, Atlanta voters approved a plan to dramatically expand public transit service and provide more alternatives to the city’s infamously congested car commute — what a writer at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution once described as “the mundane kind of misery that passes for normal.”

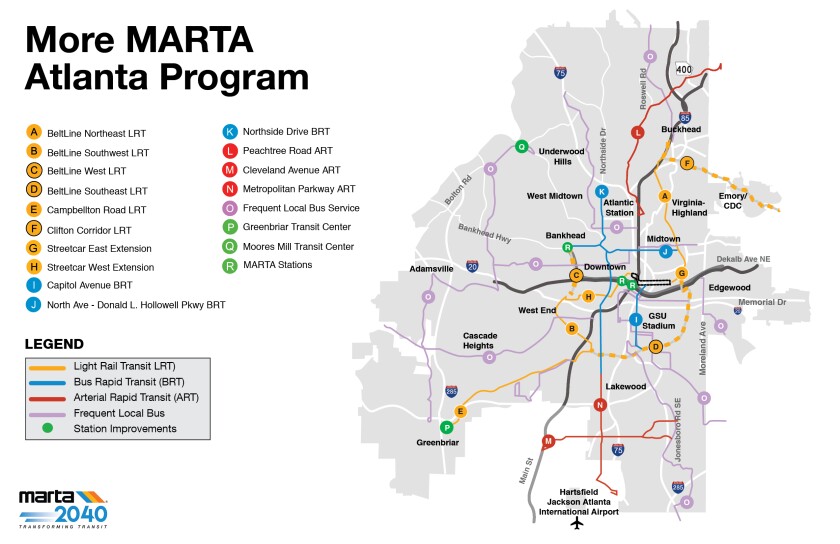

The measure was meant to bring in around $2.7 billion for the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) over 40 years through a new half-penny sales tax. With other voter-approved funds already going to support MARTA’s operations, the More MARTA Atlanta program was dedicated specifically to capital expansion: new train lines, new bus lines, new streetcar extensions and new stations.

Seven years later, little work has been completed and the scope of the program continues to narrow. MARTA is only now breaking ground on its first bus rapid transit expansion since the More MARTA program was approved. Two light rail routes that were included in the initial list of projects approved by MARTA’s board in 2018 have been switched to bus rapid transit. And the agency recently told the City Council that it will only actively pursue nine of the 17 projects that had been on its priority list.

The paring down of the More MARTA program is partly a reflection of the painful choices that transit agencies all over the country are making as they deal with pandemic-related construction delays, higher material and labor costs, lower ridership and smaller budgets. But local officials and residents also worry about MARTA’s ability to execute projects quickly enough to take advantage of the infusion of support for public transit in a historically car-centric city.

“I would have expected much more project completion or active implementation at this point, and I’m not alone. The voters feel the same way,” says City Councilmember Amir Farokhi, who chairs the council’s transportation committee. “[More MARTA] reflected a hunger for significant transit expansion within the city limits, and I think that’s why you see disappointment in the project list — because we’re taxing ourselves for more and we’re not getting more yet.”

Slow Progress, Rising Costs

Atlanta has had a tough time making progress on regional public transit. A history of racialized opposition to transit has prevented MARTA from establishing strong connections between suburbs and the city. Only 7 percent of residents commuted to work by public transit before the pandemic, according to the Atlanta Regional Commission. Voters in the 10-county region around Atlanta emphatically rejected a proposed transportation tax in 2012. But support for public transit is much stronger within city limits, and More MARTA was designed to move ahead on local projects with local support.

As of 2019, the project list included 29 new miles of light rail and 36 new miles of bus rapid transit and “arterial rapid transit,” which runs buses in traffic with signal priority. When the list of projects was approved, former MARTA CEO Jeffrey Parker wrote that it was “a signal moment that promises to fundamentally redefine how people move around Atlanta.”

The initial project list was built after a long community engagement process following the 2016 More MARTA vote. But the recent decisions to pursue BRT instead of light rail on Campbellton Road and Clifton Corridor projects were made by agency staff. MARTA officials recently told the council they wouldn’t be able to build all 17 More MARTA projects with the projected funds.

(More MARTA Atlanta)

“I think what’s probably more damaging than the paring down of the list is this huge timeline,” Givens says. “We have not seen the first BRT lane go down on the ground yet — we have not seen anything really come out of this yet. … It’s really hurting MARTA and it’s hurting the city.”

Focusing on Execution

MARTA officials declined to be interviewed for this story. The agency hired a new CEO last fall after Parker, the former CEO, died suddenly at the beginning of the year. Earlier this year, MARTA’s deputy general manager was fired without cause after only a few months on the job.

The City Council has grilled the agency about how it’s using More MARTA funds. While the program allotted some $238 million to improving bus operations over 40 years, MARTA has already put $181 million into those improvements, says City Council President Doug Shipman.

“There’s a concern of that crowding out capital projects,” Shipman says. “There’s also a question about just their ability to deliver. Yes, you have an inflationary environment, but in an inflationary environment, you have even more incentive to move quickly.”

The Atlanta metro region is projecting dramatic growth over the next three decades. While it’s known as a car-centric town, it’s too dense to be a really functional one, says Kari Watkins, a transit-focused professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of California-Davis who spent more than a decade at the Georgia Institute of Technology. But like many other cities, Atlanta also struggles to build enough density in certain corridors to support robust new transit services. The city also hasn’t effectively promoted better land use around its streetcar service, which, advocates like Givens say, is often stuck in traffic.

An extension of the streetcar to the Atlanta BeltLine, the 22-mile multi-use park and trail loop surrounding the city, is still on MARTA’s priority list of capital projects. But that project, which has been in the works for two decades, was originally envisioned as a rail line and not just a park. The vision of the BeltLine as a transit service that serves the whole city, and not just a recreational amenity for some neighborhoods, is jeopardized by a lack of commitment to seeing the rail project through, says Matthew Rao, co-chair of the advocacy group BeltLine Rail Now!

“The idea of the BeltLine that frankly didn’t happen was to build the transit and infrastructure before the gentrification… so that developers could build a different kind of neighborhood,” Rao says.

Concerns about housing affordability sit right next to those around transit and mobility, says Shipman. The BeltLine rail and other public transit projects would give people ways to live in the city without having to rely on a car. And they would let developers build lower-cost housing without having to include as many parking spaces. The housing industry is currently trying to decide “how much it believes” that new transit service is coming as it makes plans for new projects. And voters will also need a signal that continuing or expanding their investment in transit has real payoffs. So the stakes for MARTA are high, Shipman says.

“Atlanta is continuing to grow in spite of this question, so the question really is, how are we going to grow? Who are we going to grow for?” Shipman says. “Some people are going to say ‘Oh, Atlanta is going to be fine without [more transit].’ So it’s a question of trajectory.”