To address these concerns, the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (MHS) purchased a 72-acre property four miles west of Boston, which they developed into Mount Auburn Cemetery. Intended as a burial site, it also served a number of unique functions for the living.

When designing the cemetery, founders Jacob Bigelow and Henry A.S. Dearborn drew inspiration from English gardens and European garden cemeteries like the Parisian Père Lachaise, designed in 1804. The MHS maintained Mount Auburn’s natural mature forests and ponds, planted additional trees and constructed winding pathways that followed the natural curves of the landscape.

The result was not only a site for the deceased, but also a recreational site for Bostonians and tourists. By 1848, as many as 60,000visitors came annually to stroll Mount Auburn’s grounds, admiring the monuments, memorials, sculptures and landscaped setting.

The popularity of Mount Auburn ignited a rural cemetery movement throughout the country. By 1865, the United States had over 70 similarly landscaped cemeteries on the outskirts of cities, including Laurel Hill in Philadelphia, Green-Wood in Brooklyn and Mountain View in Oakland.

State governments promoted the growth of the movement through legislation. In 1847, the New York state Legislature passed the Rural Cemetery Act, allowing for the presence of commercial cemeteries (as opposed to family-owned plots or church burial grounds) throughout the state.

From Cemeteries to City Parks

As people increasingly turned to rural cemeteries for recreation, city planners and landscape architects began to design urban parks as an easy escape from the bustle of city life. As landscape designer Andrew Jackson Downing wrote, “In the absence of public gardens, rural cemeteries in a certain degree supplied their place. But does not this general interest, manifested in these cemeteries, prove that public gardens established in a liberal and suitable manner near our large cities would be equally successful?”

In 1853, the New York state Legislature set aside over 700 acres of land in Manhattan for the creation of an urban park. The Central Park Commission held a design contest and ultimately selected a plan submitted by landscape architects Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, a former partner of Downing. The two envisioned a park that, like Mount Auburn, embraced the style of romantic English gardens. They placed curving pedestrian and carriage roads amongst picturesque natural scenery.

Central Park was the first of many urban parks that were built in the 19th and early 20th centuries throughout the country. Park advocates argued the spaces provided a tranquil escape from the stressful, congested city environment. As Olmsted explained, a park within city limits allowed for “good men to come together in this way in pure air and under the light of heaven … it must have an influence directly counteractive to that of the ordinary hard, hustling working hours of town life.”

The Rise of Romantic Suburbs

The popularity of rural cemeteries and urban parks began to influence other American landscapes, including the first American suburbs.

Developed around the same time as Central Park, Llewellyn Park, N.J., is the country’s first planned residential community. Its founder, Llewellyn Haskell, sought to create a neighborhood that offered the amenities of the city while also providing an escape from urban life.

Landscape architect Andrew Jackson Davis designed the community, developing picturesque, winding roads that hugged the surrounding forests, ravines and springs.

Like the rural cemetery movement, the romantic suburb movement expanded throughout the country. Residential neighborhoods like Evergreen Hamlet near Pittsburgh, Pa., and Glendale near Cincinnati, Ohio, boasted similar picturesque landscapes.

A Changing Landscape

The rural cemetery movement had fallen out of favor by the late 19th century. These lands required extensive upkeep, and the rise of urban parks provided an alternative form of recreation for locals and travelers alike.

By the early 20th century, picturesque burial grounds were replaced by lawn cemeteries – typically green spaces with uniform rows of headstones and limited planting.

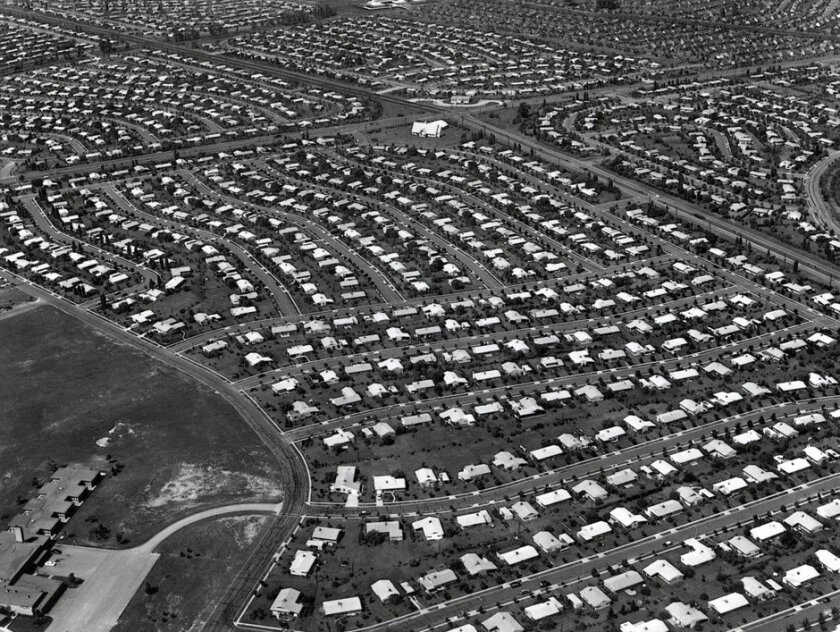

Twentieth-century suburbs were also far less picturesque and romantic than their 19th-century counterparts. Similar to the design of lawn cemeteries, later suburbs (like Levittown, Pa.) embraced uniformity over picturesque asymmetry.

Related Articles