This is far from the 45 percent reduction believed to be necessary between now and 2030 to keep the earth warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, or the outside limit of 2.0 degrees envisioned in the Paris Agreement. Parties agreed to review their contributions by the end of 2022, leading COP26 President Alok Sharma to express the view that the 1.5 degree goal might still be alive. However, he said, “its pulse is weak.”

Buildings are responsible for an estimated 40 percent of CO2 emissions — 28 percent from operations and the rest from building materials and construction. Building energy codes are a fundamental strategy for reducing these emissions by setting and enforcing efficiency standards that can apply to both new construction and retrofits.

Kim Cheslak, director of codes for New Buildings Institute, works to help local governments make the most of code adoption and implementation. Cheslak earned a master’s degree in architecture, but code was never part of the curriculum.

“The one thing I learned about codes in architecture school is that codes are the bare minimum that we’ve all agreed our buildings need to meet so we don’t kill people,” she says. Traditionally, this has meant such things as structural soundness, air quality, escape routes for emergencies or the ability to withstand an earthquake.

It may be time to expand the concept of building safety outward. Climate impacts once predicted to be decades in the future are harming people now. Emissions from buildings are a big part of the problem, especially those resulting from energy wasted by inefficient buildings.

Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm characterized building codes as a “huge weapon” in the fight against climate change in a video address to attendees at the recent annual conference of the International Code Council.

“It’s time to move past traditional minimums,” she said. “It’s time to really start thinking about how codes could quickly and aggressively raise efficiency, raise resilience and even raise clean energy capacity.”

Uphill Battle

In July the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) issued determinations from its analysis of the latest model energy codes for residential and commercial buildings. It concluded that the 2021 version of the International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) could lead to an almost 9 percent reduction in emissions, as well as over 9 percent cost savings in residential buildings relative to the 2018 code.

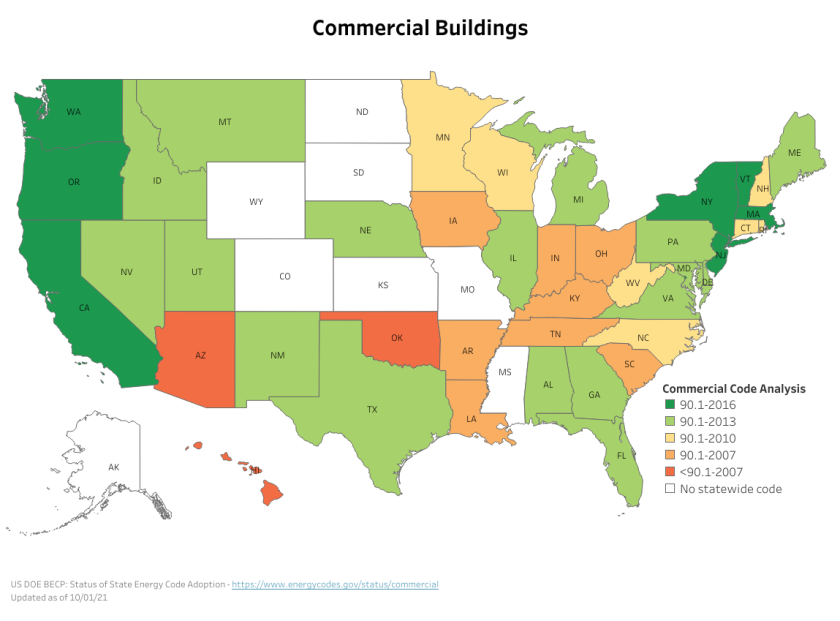

It also compared the 2019 version of the benchmark for commercial building energy codes, ANSI/ASHRAE/IES Standard 90.1, to the 2016 edition and estimated that it could reduce both emissions and energy cost by more than 4 percent. States are obligated to certify to DOE that that they have reviewed the new codes and made a determination as to whether their own codes should be updated, but they are not required to make such changes.

DOE maintains maps showing the status of state-by-state energy code adoption; the most recent update was Oct. 1, 2021. Color coding ranges from red (the oldest codes) to dark green. A handful of states are blank; these are home rule states, where code adoption is done at the local level.

DOE’s residential map shows the majority of states using versions of the IECC from 2009 or earlier. Commercial standards are more up to date, but one in three statewide codes is based on standards from 2010 or previous years.

Dozens of bills related to energy code issues have been introduced in the past year, some pushing well beyond minimum standards or encompassing workforce development and training requirements for code enforcement personnel.

A Change of Mindset

As she works to help local governments update their code, Cheslak often encounters pushback regarding the amount of training and education it takes to implement code changes. Those affected include building department officials involved in permitting and inspection, designers, construction companies and workers.

Cheslak has worked as a building code official, doing plan reviews and inspections, and is well aware that time and resources are limited. “Everyone wants their permit yesterday — even if they didn’t apply for it yesterday, they want it yesterday.”

To the extent that changes aren’t understood, there’s more work, more frustration and more lost time and money for all concerned. The infrastructure bill signed this week addresses this reality, allocating $225 million for grants to support implementation of updated energy codes as well as $10 million for career skills training grants.

The transformational change necessary in response to a climate “code red for humanity” will require more than money and better code. It’s also a matter of the mindset of everyone involved in buildings, including those who train the professionals who design them. It’s vital for local governments to hire and train more employees with 21st century expertise.

“We’ve managed to pass the buck,” says Cheslak. If a buyer doesn’t get a building that performs as expected, he blames the designer. The designer blames the official who gave the permit, or the construction company. The permitting official blames the inspector. The blame goes back to the designer for a bad design.

“At a certain point, we all have to dig in on our responsibility in the chain,” she says. “We have to stop pointing our fingers at other people.”