In 2020, North Carolina briefly limited the practice of entering and reporting to the DMV failures to comply for nonpayment of court debt. But the state has resumed automatically suspending licenses when individuals don’t pay court debts fast enough — even as COVID-19 still grips the country, pandemic unemployment compensation has ended in the state and unemployment remains high.

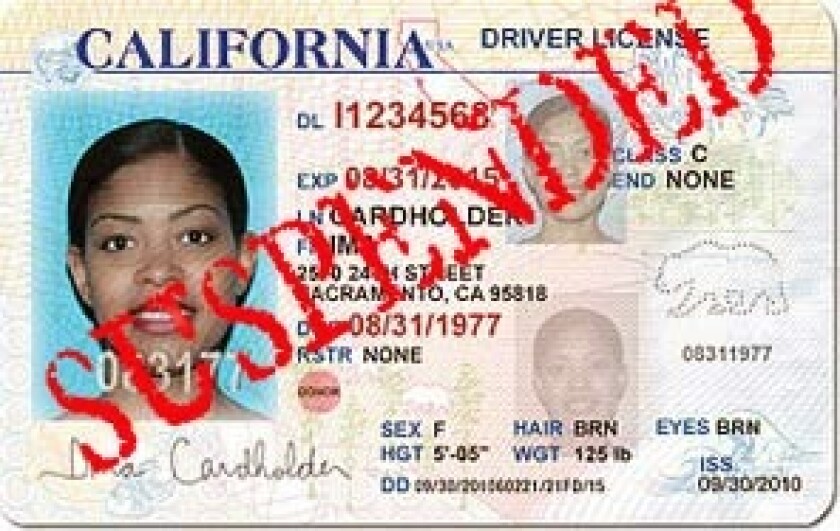

Suspending a license for failure to pay (known as “failure to comply, or FTC) may seem a valid strategy to encourage payment. But research shows the practice unjustly imposes compounding hardships and long-lasting consequences for day-to-day life, particularly on poor communities and communities of color. For example, Black people are four times as likely to have an FTC suspension as white people.

Because such a suspension lasts until you pay all the debt, it’s often more punitive than a drunk driving suspension, where a license is automatically restored after 12 months.

In addition to the original ticket, you may also owe dozens of $5 to $30 fees. And that is often just the beginning, as an FTC can spawn the vicious cycle of even more costs and extended suspensions.

Research analyzing FTCs in North Carolina shows that tens of thousands of FTCs last for years, with only a minority paid off within 120 days. Thus, hundreds of millions of dollars in fines and fees go uncollected every year. The state will likely never collect a large proportion of these debts.

Seventeen states, including neighboring Virginia, have stopped suspensions due to failure to pay. Several others have limited the practice. There is no reason North Carolina could not follow suit. But simply stopping new suspensions is insufficient. Without retroactive relief, hundreds of thousands of North Carolinians will continue to suffer from the racial and economic injustices caused by their suspensions.

The effectiveness of other measures vary. Those that remove cost barriers, like waiving or reducing unaffordable DMV fees, are beneficial. Nevada, for instance, just ended debt-based suspensions and will reinstate existing suspensions without additional DMV costs.

Yet, other measures are likely to have no impact or backfire. For example, North Carolina is considering allowing petitioners to convert traffic fines and fees to civil judgments and restore licenses after 12 months. But a year is too late, particularly if you have lost your job or home or incurred new debt. Plus, converting debt to a civil judgment may ultimately prove more punishing by enabling debt collectors to pursue you even more aggressively.

Almost 400,000 N.C. drivers have had their licenses suspended for an FTC. An additional 827,000 people, disproportionately people of color, have suspensions for failing to appear (FTA) in traffic court.

Like FTCs, financial limitations likely also underlie FTAs, and indeed, getting to court becomes much more challenging when you cannot drive. Although a few counties’ efforts have reduced suspensions, the problem is too enormous for these programs, alone, to solve.

These abusive practices have gone on for many years, affecting hundreds of thousands of people. Far-reaching action is urgently needed. We need to change the law.

North Carolina lawmakers should consider the economic and racial justice benefits of stopping driver’s license suspensions for failure to pay or to appear in court. We also need to restore rights for the vast numbers of people who have lost their licenses. Only then can a million-plus North Carolinians get back to living their lives.

William Crozier is Research Director at the Wilson Center for Science and Justice at Duke Law. Yvette Garcia Missri is Executive Director of the Wilson Center.

©2021 The Charlotte Observer. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.