Appointments for the Long Run

Justices serve for life (on good behavior). Thanks to increased longevity, a person appointed in her or his 40s can now expect to serve for 30 or 40 years. There has never been a successful impeachment of a Supreme Court justice in American history. Once they take their seat on the high court, justices have no contractual obligation to vote as the president who appointed them might wish. And they frequently disappoint.Thomas Jefferson’s nemesis John Marshall (an Adams appointee) served for 34 years. He ranks fourth on a longevity list that includes William O. Douglas (36 years), Stephen Johnson Field (35 years), and John Paul Stevens (34 years).

Earl Warren (right) and President Eisenhower before the betrayal.

President Jefferson appointed three men to the Supreme Court between 1801 and 1809, two of whom failed to decide cases in line with the strict constructionist, states’ rights philosophy of the Sage of Monticello. Reflecting on the failure of his appointees (not just court appointees) to remain loyal, Jefferson spoke resignedly of “appointments and disappointments.” And in 1807 he wrote, “Every office becoming vacant, every appointment made, [brings] me donne un ingrat, et cent ennemis [one ingrate and 100 enemies].

A century later, on July 10, 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt tried to thread the needle on the subject of party loyalty and judicial independence, “In the ordinary and low sense which we attach to the words ‘partisan’ and ‘politician,’” he wrote his closest friend Henry Cabot Lodge, “a judge of the Supreme Court should be neither. But in the higher sense, in the proper sense, he is not in my judgment fitted for the position unless he is a party man.... Now I should like to know that Judge [Oliver Wendell] Holmes was in entire sympathy with our views, that is your views and mine . . . before I would feel free in appointing him.”

Roosevelt did appoint Holmesto the Supreme Court. But after Holmes voted the wrong way on a case important to Roosevelt, TR said he could “carve a stronger backbone out of a banana.” Roosevelt is famous for many things, not least because he uttered the best insults of any American president. When William McKinley hesitated to declare war on Spain in 1898, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Roosevelt famously said McKinley “had no more backbone than a chocolate éclair.”

Oliver Wendell Holmes.

Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Felix Frankfurter (1939-1962) to the court, convinced that he would have a reliable liberal who would vote to protect FDR’s New Deal programs. He was sorely disappointed when Frankfurter migrated from an earlier liberal, almost radical legal perspective to a clearly conservative one.

Life Tenure and Independence

After two of his nominees were rejected by the Senate (one because he was a racist, the other because he was a mediocrity), Richard Nixon appointed Harry Blackmun, who won Senate confirmation in 1970 and served for 23 years. Nixon expected Blackmun to be a solid conservative, but the justice moved steadily towards the progressive end of the spectrum. He famously wrote the majority opinion in Roe v. Wade in 1973, for which he will be forever remembered in infamy by pro-life advocates.Both of Ronald Reagan’s appointments to the court veered from what he expected when he selected them. The first woman ever to serve on the court, Sandra Day O’Connor (1981-2006), voted often enough with the liberals on the court to earn a reputation as a genuine swing vote, particularly in her last decade of service. Justice Anthony Kennedy (1988-2018) became one of the most significant swing votes in modern Supreme Court history. Justice Kennedy joined liberals about a third of the time, much to the dismay of Reagan Republicans.

The current chief justice, John Roberts, appointed by George W. Bush in 2005, is a committed institutionalist who is doing what he can to prevent the court from becoming an overtly political branch of the United States government. He is also something of a centrist. He raised the wrath of the right by voting to uphold Obamacare in 2013. He may take on the role of swing vote as the court veers toward increasingly conservative decisions.

The point of this brief survey of Supreme Court history is that life tenure produces a kind of magical independence (not to mention unassailable job security) for anyone who gets the necessary two-thirds vote in the United States Senate. No matter what the sponsoring president thinks, says, or presumes about a nominee, once that justice is confirmed she or he is free to establish a judicial philosophy that owes no legal allegiance to the president who appoints or the Senate that confirms. The president can rage about bananas and betrayal, but there is literally nothing she or he can do to intimidate an independent justice.

Hearings Reveal Little

The question now dominating the national conversation is what we can expect from President Trump’s third Supreme Court appointee, Amy Coney Barrett. She appears to be a devout Catholic conservative, decidedly pro-life, critical of the Affordable Care Act, and dedicated to an originalist interpretation of the U.S. Constitution. By this she seems to mean that she regards it as the duty of the court to be reactive not proactive, to decide cases by what appear to be the original intentions of the Founding Fathers (to the degree that we can ascertain them), and not to “legislate from the bench” by stretching the Constitution to accommodate our contemporary notions of enlightenment or political correctness.She wishes to pattern herself after her mentor, Justice Antonia Scalia (served 1986-2016), for whom she served as law clerk in 1998-1999. The question everyone wants to resolve is how her judicial philosophy will negotiate with her deep personal convictions, and what impact her personal convictions might have on her judicial decisions. These are eminently fair and legitimate questions. Unfortunately, we are unlikely to learn much from the Senate hearings on Capitol Hill.

The Senate confirmation hearings for Ms. Barrett and most other justices appointed in the last 30 years have become an unproductive form of political carnival. The nominee strains to be bland, refuses to explain how she or he might rule on “hypothetical” cases, evades legitimate questions for which we all know she or he has an answer, distances themselves from their memos, emails, op-ed pieces, and law review articles that the Senate staff has diligently unearthed, and lectures senators on the importance of judicial independence.

Meanwhile, many of the senators on the Judiciary Committee, knowing in advance that the nominee is going to refuse to get down to specifics, grandstand and badger (the nominee or each other), and mostly perform for the cable news channels, using much of their allotted time to make political statements rather than question the nominee. When they do focus on the nominee, there is a numbing repetitiveness to their questions, indicating either that the senators are not actually listening to the proceedings, or are merely using the hearings to assure their own base of their ideological purity.

Thomas Jefferson was probably right. He believed that a president of the United States had a right to surround himself with men — all men then — of his own political stamp and constitutional philosophy, that the role of the Senate was not to determine if it approved of the nominee’s judicial philosophy or legal record, or whether it liked the nominee, but only to determine if he was generally qualified to be a justice of the Supreme Court. In other words, if President Ronald Reagan wanted Robert Bork to serve on the court, the Senate ought to acquiesce, unless it could find proof that he was unqualified to serve. Elections matter.

Barrett, the U.S. Senate and America

Ms. Barrett finds herself in a nearly impossible position. She cannot possibly divulge the nature of the conversations she has had with President Trump or his staff, though we know that the president has declared unequivocally, and many times, that he would only appoint justices who oppose the Affordable Care Act (which will come before the court a week after the election), and who agree to try to overturn Roe v. Wade. If she pledged to serve the president’s interests on these or other cases, tacitly or overtly, the American people have a right to know that, whether they agree or disagree, because if she is confirmed she will immediately become one of the most powerful individuals in America for many decades, with the capacity (along with just eight others) to determine questions about racial equity, voting rights, reproductive health, separation of church and state, the status of the LGBTQ community, gun ownership, access to health care, and much more. The future of the United States should not be determined by way of private winks and assurances that play out behind a monotonous screen of judicial professionalism. Surely in a democratic society the people have a right to know if a Supreme Court nominee carries a political agenda into her court tenure. Too much is at stake to accept anything less than political candor. We do not appoint Supreme Court justices for a two- or 10-year term, but for life. We have a right to know.

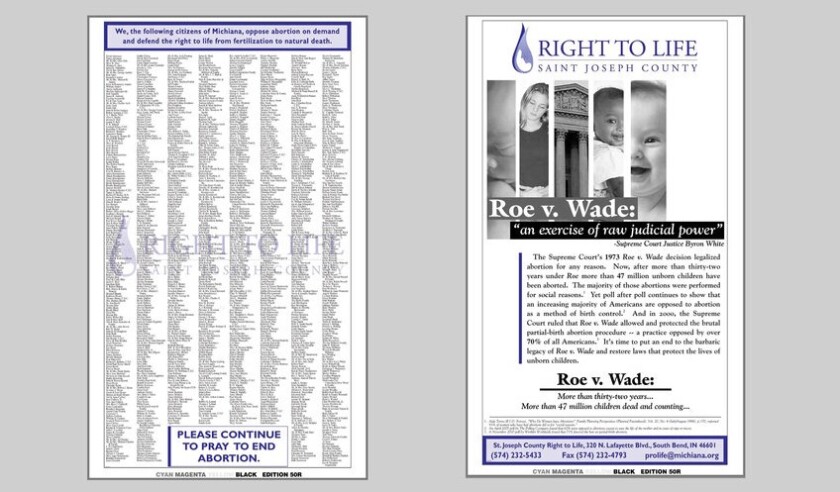

The South Bend right-to-life newspaper petition.

If the president had not made it unmistakably clear that he has several non-negotiable “litmus tests” for his judicial nominees, Ms. Barrett might be able to legitimately claim that she cannot possibly know what she would do about any given national issue until she studied a case actually placed before the court. This is precisely the responsible perspective of any judicial nominee, because cases are decided by what’s in them, the facts of the case and their relation to the Constitution, not by gut responses, but it may ring hollow if Ms. Barrett has already provided secret assurances that she will vote to overturn Roe and Obamacare and (possibly) side with Donald Trump in the event that the outcome of the Nov. 3 election winds up in the hands of the Supreme Court.

If Amy Coney Barrett is in a difficult position as she faces the grilling of Democrats on the Senate Judiciary Committee, the Senate is also in an unenviable position. It would be insane for U.S. senators not to try to learn everything they can about a person they are likely to appoint for life. Like it or not, whatever one learns in a high school civics course, the Supreme Court today is a political body that wades into policy questions of the greatest national importance while pretending to be a dispassionate and nonpartisan referee. The Warren Court did not merely read the Constitution rigorously in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. It moved the United States toward greater enlightenment. It led when the routine political process was paralyzed. But just 56 years earlier, in Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court read the same Constitution and determined that “separate but equal” facilities for African Americans were perfectly legitimate. No matter what the “originalists” and the “strict constructionists” say, the court has to keep pace with the changing demographics, morals, and ideals of the most dynamic and fast-paced nation in human history.

On March 6, 1857, Chief Justice Roger Taney, in the notorious Dred Scott case, declared that African Americans had “No rights which the white man was bound to respect.” Needless to say, nobody but the Proud Boys or David Duke would make such a claim today. Like it or not, the U.S. Constitution is a living document that tries to stay within the broad outline of the 1787 document to create “a more perfect union,” but makes adjustments to circumstances that the Founding Fathers could not possibly anticipate (cyberporn, electronic surveillance, automatic rifles, DNA). Every member of the Supreme Court brings baggage to the bench. Each justice has politics, a set of presuppositions, prejudices, notions, blindness, and biases. Under the best circumstances they manage to keep them partly in check. But almost no justice in U.S. history has been objective and dispassionate in the ways demanded or proffered in the Senate Judiciary Committee charades.

The Democrats on the Judiciary Committee feel intense, perhaps unprecedented, pressure to try to ascertain what Justice Barrett is likely to do if she reaches the court, because the country is already voting in what is widely regarded as the most important election of this era. If the nomination were postponed to February, it is not clear that she would be confirmed. In other words, if this nomination had occurred two years ago, the principle that elections matter would seem to settle the case. But if elections matter, surely this one does and we are not only on the eve of it, but actually engaged in it in real time. If President Trump loses the election and the Senate changes hands, that would seem to be an expression of the will of the American people, and it is unlikely, as the polls clearly show, that a majority of Americans would want to see a judicial nominee confirmed by a discredited president and a lame-duck Congress. If he wins re-election and the Republicans hold the Senate, he has a right, as Jefferson said, to expect people of his political stamp to be confirmed.

Bringing Baggage to the Bench

The problem is further complicated by the fact that Amy Coney Barrett has not been silent on policy questions likely to make their way to the Supreme Court. All evidence indicates that Barrett personally opposes abortion. Will that influence her judicial thinking? How could it not? She delivered an anti-abortion lecture to the Right to Life club at the University of Notre Dame, where she taught law, and she joined an anti-abortion-rights faculty group. Barrett also signed an anti-abortion petition in South Bend in 2006, which took the form of a full-page newspaper advertisement sponsored by an organization called St. Joseph County Right to Life. “I signed it on the way out of church,” Barrett told Sen. Patrick Leahy of Vermont this week, as if to suggest that she was not fully cognizant of what she was signing. “It was consistent with the views of my church, and it simply said we support the right to life from conception to natural death.”If confirmed, would Justice Barrett set aside her personal beliefs and faithfully follow the law wherever it led, even if it violated her strongly held convictions? Barrett has assured senators that this is her intention: “My personal views don’t have anything to do with the way I would decide cases,” she told Sen. Leahy. “I don’t want anyone to be unclear about that.”

Really? Admittedly we live in a cynical age, but does anyone really believe that? If the president insists that any person he nominates must oppose Roe, and if Ms. Barrett is on the record in so many ways declaring that Roe v. Wade produced a “barbaric legacy,” what reasonable person can believe her, or anyone else, who says, “I can’t pre-commit . . . because I don’t have any agenda”? The same would be true, of course, of a Democrat appointee, saying he or she had no agenda, no preconceived views of abortion or health care or school prayer.

Barrett has also left a paper train with respect to the Affordable Care Act. As a University of Notre Dame law professor, Professor Barrett wrote a 2017 law review essay in which she said, “Chief Justice Roberts pushed the Affordable Care Act beyond its plausible meaning to save the statute. He construed the penalty imposed on those without health insurance as a tax, which permitted him to sustain the statute as a valid exercise of the taxing power. Had he treated the payment as the statute did—as a penalty—he would have had to invalidate the statute as lying beyond Congress's commerce power.” In 2015, on NPR, Barrett said she thought dissenting justices in the Obamacare case of 2013 had “the better of the legal argument.”

This would seem to be a fair indication of how Barrett might vote on an ACA case. Her law review article was a legal argument, not an op-ed piece in a church newsletter. By what logic can she edge away from that law review essay without declaring either that she has changed her mind or that since she published it she has had the opportunity to think more deeply about the issue?

Barrett also appears to advocate the banning of the medical procedure called in vitro fertilization. In her Senate testimony on Oct. 13, Barrett declined to say whether she views the criminalizing of in vitro fertilization as constitutional, describing it as an “abstract question.” But it is not an abstract question. Barrett signed a petition in South Bend that declared an absolute commitment to “the right to life from fertilization to natural death.” Jackie Appleman, the executive director of St. Joseph Right to Life, explained that the petition “would be supportive of criminalizing the discarding of frozen embryos or selective reduction through the IVF process.” In other words, Ms. Barrett signed on to the position that in vitro fertilization should be outlawed because it discards the eggs (human lives) that are not fertilized in the process. Currently about 4 million births per year in the United States are the result of in vitro fertilization.

The Legacy Question

President Trump has put Ms. Barrett in a very difficult position. If she is confirmed, and she votes against Roe, against Obamacare, or for Mr. Trump in a contested election, she will now always bear the stigma of having made an injudicious “corrupt bargain” to get herself on the court. If she votes the other way on any of these issues, she will be regarded by conservatives as a political turncoat. By denying that she has had any discussions about Roe and the Affordable Care Act with the president, or that she has been pressured to vote his way, Ms. Barrett strains credulity. It is impossible to believe that Mr. Trump did not at least attempt to force concessions from her before advancing her candidacy. A president who has made personal loyalty the shibboleth of his administration is unlikely to have had a hands-off approach on an appointment of this colossal magnitude.If Amy Coney Barrett is confirmed by the United States Senate, there is no guarantee, of course, that she will continue to hold views congenial to the president who appointed her. Many Supreme Court justices have tormented their sponsors by developing an unpredictable judicial outlook. The big losers in our current system of nomination, advice, and consent are the American people, no matter what their politics. When nine unelected and unaccountable individuals make fundamental decisions, including exceedingly personal decisions, for a third of a billion Americans, “we the people” have the right to know a great deal about how that individual sees the world, how he or she is likely to respond to the key issues of our time, and how he or she plans to balance her politics and personal convictions on the one hand with their judicial analysis on the other.

For more of Clay Jenkinson's views on American history and the humanities, listen to his weekly nationally syndicated public radio program and podcast, The Thomas Jefferson Hour. Clay's most recent book, Repairing Jefferson's America: A Guide to Civility and Enlightened Citizenship, is among the core readings for a five-week online humanities course Clay will teach on the state of the U.S. Constitution immediately following the election, beginning Nov. 7. Learn more and register for “The Future of Constitutional Democracy” today.