Toward American Separatism

So, what’s the remedy? Taking his cues from the British people’s 2016 decision to leave the European Union (Brexit), French wonders if we should begin to brace ourselves for successful secessionist movements in the United States. In chapters 12 and 13 of Divided We Fall, French writes a fictional account of Calexitand Texit, the secessions of California, with one-tenth of the U.S. population and the fifth largest economy in the world, and Texas (29 million, the 10th largest economy in the world). Though I admire this book, I found these fictional chapters unconvincing. In other words, I came away from these chapters less convinced of the possibility of serious secession in the United States than when I began to read them.Before reviewing earlier secession movements in American history, I turn to the Founding Father with the most cheerful outlook on American separatism, Thomas Jefferson. In a letter to John Breckinridge of Kentucky in Aug. 12, 1803, Jefferson wrote:

The future inhabitants of the Atlantic & Missipi [sic] States will be our sons. We leave them in distinct but bordering establishments. We think we see their happiness in their union, & we wish it. Events may prove it otherwise; and if they see their interest in separation, why should we take side with our Atlantic rather than our Missipi descendants? It is the elder and the younger son differing. God bless them both, & keep them in the union, if it be for their good, but separate them, if it be better. Typical Jefferson, that fierce and consistent believer in the right to self-determination, even within the boundaries of the United States! During the course of his life (1743-1826), when he descended from theory to actual political situations, Jefferson actually discouraged secession movements on the principle that America’s destiny would be better served by national unity and also that it is better to keep disputes within the national family than fracture into what would be smaller and smaller units.

There were quite a few secession gambits in Jefferson’s time. Usually it was New England that sought to detach itself from the “slaveocracy” of the southern states. One attempt that percolated during Jefferson’s first term as president (1801-05) fell apart when he was re-elected in by a landslide in 1804. The second, much more serious attempt came during the administration of Jefferson’s successor James Madison. The “Hartford Convention” of disgruntled New England Federalists met between Dec. 15, 1815, and Jan. 5, 1816, in Hartford, Conn., to discuss secession. The convention proposed an end to the Three Fifths Clause, and a requirement that new states could only be admitted after a two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress, a national declaration of war, and laws restricting commercial trade. There was a great deal of huff and puff, born mostly of frustration about what the New Englanders regarded as the “Virginia Dynasty’s” mishandling of “Mr. Madison’s War,” the War of 1812. The Hartford movement collapsed quickly after Andrew Jackson’s stunning victory in the Battle of New Orleans on Jan. 8, 1815.

From the Civil War to Cascadia

The Civil War (1861-1865) was, of course, the ultimate American secession movement. It failed, but at the cost of 618,222 lives. The tragic legacy of what some in the South still call “the war of northern aggression” continues to this day.In the shadow of the Civil War, all subsequent secession movements have seemed harmless and only half-serious. Northern California periodically threatens to declare itself the “State of Jefferson,” and northern California, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia are sometimes fancifully projected as a future Cascadiaor even Ecotopia, as novelist Ernest Callenbach termed it in his fascinating 1975 book, Ecotopia: The Notebooks and Reports of William Weston. Callenbach’s 1981 prequel, Ecotopia Emerging, is also worth reading. More recently we have heard of the Republic of Lakotah on the northern Great Plains. In every state with a Blue-urban, Red-rural split, we occasionally hear largely rhetorical rumbling about internal secession.

After the re-election of Barack Obama in 2012, secession petition campaigns were initiated in all 50 states, and in six of them — Louisiana, Alabama, Florida, Tennessee, Georgia, and Texas — the threshold of 25,000 signatures was met, requiring some sort of formal response from the United States government. Aside from a small minority of true believers, these sorts of movements are largely designed to register unhappiness rather than to initiate an authentic attempt at disunion. I’ve been reading about American secession movements (in northern Michigan, in northern California, in the Pacific Northwest) all of my life. Things never move very far beyond some heated town meetings, yard signs, and billboards out along the highway.

Just as the province of Quebec in Canada and Scotland in the United Kingdom frequently make moves towards secession, in the end the people of those jurisdictions have so far pulled back from so grave (and seemingly irrevocable) a decision.

Frustration Signaling

It’s not clear whether French is really serious about the possibility of the secession of states (Texit, Calexit) or whole regions of the United States. Most Americans subscribe to some version of American Exceptionalism — the idea that there is something unique, special, perhaps even magical about the United States. Even the number of states — a perfect 50 — seems somehow ordained or at least wonderfully appropriate, which is one reason the idea of adding the District of Columbia or Puerto Rico to the mix meets so much resistance. The concept of Manifest Destiny (that God’s providence has somehow willed and protected the American project, especially as we moved west from the original 13 states) is not altogether extinguished in the American spirit.

Author David French.

Brexit(Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union) may have been a bold, even revolutionary move in 2016, but it was not unpredictable. Britain has always had a recalcitrant relationship with the EU and — historically — with Europe. A nation that refused to embrace the Euro was never going to be a full partner in the EU. Britain’s unique status as an island that is partly European and partly something else, a “sceptered isle” that has at least twice been saved by the English Channel from an invasion from the continent (Napoleon 1803-1805, and Hitler 1940-1942), distinguishes it somewhat from the kind of internal polarization that French sees building to a fundamental crisis in the United States.

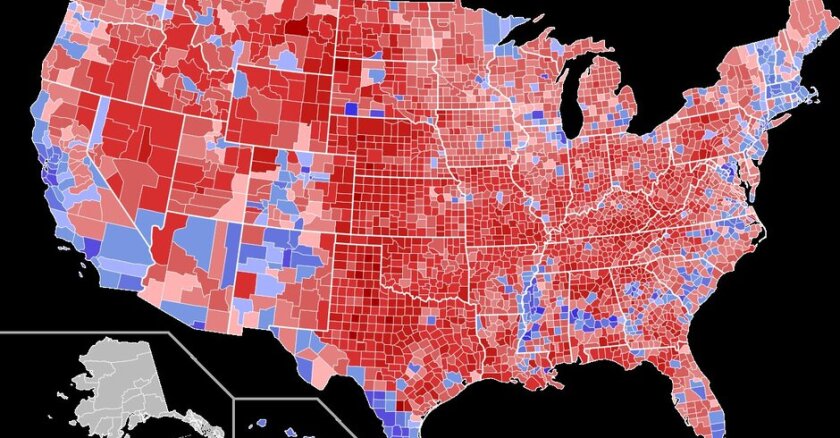

Still, secession might not be such a bad idea. It seems unmistakable that there are at least two Americas now, the Blue coastal zone, plus the great inland cities, and the liberal city-states like Madison, Wis., and Boulder, Colo.; and the Red heartland embracing all or most of the Southern Confederacy, the Great Plains all the way up, and some parts of the mountain West. The denizens of Sand Point, Idaho, or Rawlins, Wyo., see the world differently from the citizens of New York or San Francisco or Iowa City, Iowa.

It used to be that these two Americas shook their heads at each other and thanked their lucky stars that they did not live in the other zone. Now they shake their fists at each other and frequently enough accuse the other of being aliens who a) are not really good Americans at all, and b) are enemies who want to destroy this country. French points to the ways in which the American people are increasingly gravitating to regions that share their own political outlook (rather than staying and duking it out at home), and the rise of “landslide counties” where “one presidential candidate wins by at least twenty points.”

Fault Lines in a Fractured America

If we actually fractured the nation into American Blue and American Red, but kept the Interstate Highways and the airports open, and negotiated a common trade and currency system like the EU, we might actually be happier — certainly less frustrated. Maybe Jefferson is right: there is nothing magical about a single continental union.David French has what he regards as a more promising plan. Divided We Fall makes two proposals that might hold us together. First, we should recommit ourselves to the wisdom of Federalist No. 10 (written by the great James Madison), wherein the “Father of the Constitution” suggested that America could avoid tyranny by embracing a geographically splayed, pluralistic confederation of varied regional identities, economies, habits, factions, parties, interest groups, and social mores, in which one faction (or party or region) would always be balanced and offset by the others, and therefore no single party or region would ever be able to dominate. Like most 18th-century men, Madison was a Newtonian who believed in the thermodynamics of power and equal and opposite reactions. In other words, we don’t have to agree on every policy question as long as we agree on a few things: union, a working consensus in foreign policy, and the untouchability of the Bill of Rights.

French’s second (and related) proposal is that we just learn to accept that we are not now and have never actually been a single unified country. Or, as he puts it, let California be California (liberal, progressive, pro-choice, pro-environment) and at the same time let Tennessee be Tennessee (pro-life, pro-gun, pro-development). If Roe v. Wade is overturned, that doesn’t outlaw abortion in the United States. It means that abortion will be legal in some states and not legal in others.

According to French, in a nation as geographically vast as ours, a nation that has always had regional sub-cultures, it is a mistake to try to forge a single national identity. Let the South and the Great Plains be Red America, and if you don’t like it there, vote with your feet and move to Oregon or Rhode Island. Let the coasts and parts of the Midwest be Blue America, and if you don’t like it there, vote with your feet and move to Arkansas or North Dakota. French believes we need to relax a little and shrug off the differences that seem to be driving us apart. It is not necessary to have a one-size-fits-all national identity. But don’t mess with the Bill of Rights.

Unfortunately, there is no longer a national consensus even on the guarantees of the Bill of Rights. Think of the fierce debates about religion and the First Amendment, firearms and the Second, about Fifth Amendment “takings,” about what constitutes “cruel and unusual punishments,” and whether the Ninth Amendment protects the kind of privacy that is contemplated in Roe v. Wade.

More Light, Less Heat

French sees not just one but two culture wars in America today, the better known one that gets oversimplified as Red versus Blue, and an “even deeper struggle — between decency and indecency.” French knows whereof he speaks. He is a self-defined Christian conservative Republican who has given much of his career to defending religious expression against those who would enforce a rigidly secular agenda in the public square, but after he began criticizing Donald Trump and his allies in 2015, French and his family were subjected to a vicious and appalling barrage of online aggression.“My youngest daughter is black, adopted from Ethiopia, and the alt-right took pictures of her seven-year-old face and Photoshopped her into a gas chamber, with Trump Photoshopped in an SS uniform, pushing the button to kill her.” One far-right goon hacked into a phone call between French’s wife and her elderly father “and began screaming profanities at her and berating her about Donald Trump.” This is not only heartbreaking, but deeply alarming.

French’s plea is that we lower the temperature of our national shouting match, learn to live grumblingly with each other, and stop seeing the culture wars as a zero sum game in which the other side needs not only to be beaten at the polls, but destroyed, by way of street violence if necessary.

As with most such books, the diagnosis is more convincing than the prescriptions, but at this time when the United States does seem palpably to be dis-integrating month by month, Divided We Fall deserves serious attention.

Divided We Fall: America’s Secession Threat and How to Restore Our Nation

David French

St. Martin’s Press. 288 pages. $28.99.

For more of Clay Jenkinson's views on American history and the humanities, listen to his weekly nationally syndicated public radio program and podcast, The Thomas Jefferson Hour. Clay's most recent book, Repairing Jefferson's America: A Guide to Civility and Enlightened Citizenship, is among the core readings for a five-week online humanities course Clay will teach on the state of the U.S. Constitution immediately following the election, beginning Nov. 7. Learn more and register for “The Future of Constitutional Democracy” today.