The Jan. 6, 2021, mob attack on the U.S. Capitol stands as a prevailing symbol of the country’s present-day polarization. But while the brutality of that day sits in the minds of many Americans as unprecedented, historian Joanne Freeman reminds us that violence within the Capitol has a long history.

Governing: The history of this country has been fundamentally and repeatedly compromised by race. As a historian, what do you make of that?

Governing: This was a crisis in American life, with violence played out on the floor of the House of Representatives. It wasn’t merely about slavery — it was about fear of loss of power — but publicly it was about slavery.

Joanne Freeman: The book covers the 1830s, 1840s and 1850s. Huge growth was happening, and every new state raised the issue of whether slavery was going to be bound to the South or allowed to spread. But it was also really about maintaining power at a time when it was not clear where national power was going to go. It was about a group of people not sure whether they had the demographics to hang onto power by democratic means. Violence was awfully handy in that situation. If you could intimidate people into backing down, or into assuming that you actually were a majority, that was a powerful maneuver. In the book, I show Southerners threatening and intimidating Northerners into backing down on a lot of things, but more often than not on the issue of slavery. The key was that they were violent sometimes. They didn't have to be violent all the time. They just had to seem willing to be violent. If you were a Northerner and you were called out by a Southerner who might challenge you to a duel or pull out a knife or a gun, you were not going to confront that person. You were going to sit down and shut up. That's really effective.

Joanne Freeman: Yes, but I discovered that the loudest abolitionists and anti-slavery advocates all used some sort of shtick to keep themselves safe and to gain an edge. Joshua Giddings of Ohio, for example, was a big guy who wasn’t afraid of fighting. He said whatever he wanted, and then basically said, "If you want to fight me, come on and bring it."

Governing: Did their behavior harden opinion to the point where there had to be a fundamental breakdown, or was that a process that might have worked?

Joanne Freeman: There is a school of historians who argue that it was blundering congressmen who brought the war on. I don't think that's the case because they weren’t the ones causing the problems. Some of them were in fact meeting off the floor to try to negotiate a compromise. What I do think is that the nation was taking its tone from the reports they were seeing in newspapers about these brawls and fights. It wasn’t that the congressmen were upsetting the nation, but they were part of the cycle of the slavery question, sectionalism, outrage at people taking something from you, of what was seen as a struggle for the essence of America.

There have been moments when people knew that something fundamental about the United States was up for debate, and those have been violent times. The 1790s was one, when they were asking, “What is democracy? How does it work? How much power do people actually have?” The 1850s was another, and slavery was the big issue. The 1960s was another, and that was about civil rights. Now we are in another one of those moments, and we can pin many things on it, but one of those things is race.

(Library of Congress)

Joanne Freeman: As the slavery issue was beginning to peak in the late 1840s, this mind-blowing technology came along. Suddenly, within 45 minutes, the nation could get news. People thought this was a wonderful democratic thing. But there was not a lot of wiggle room. There was an episode in 1850 where one senator almost shot at another. Nothing happened and everyone finally sat down, but John Parker Hale quickly pointed out, "If we don't announce that we're investigating this incident, within 45 minutes the nation is going to assume that we're here slaughtering each other. We have to say something now before we lose control of this story." You can feel the power of the telegraph in that moment. It was like the power that social media now has to take control of a narrative out of the hands of the people who are used to having control.

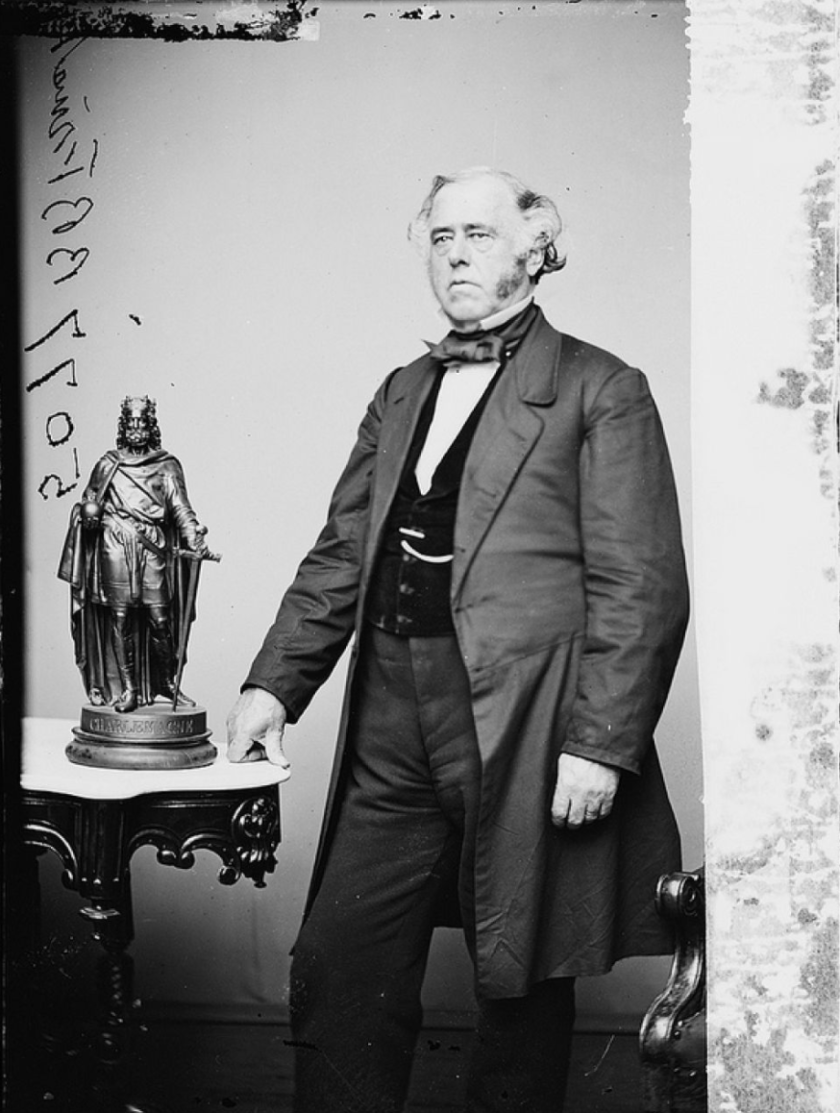

Governing: The main character in your book is Benjamin Brown French, and you depended a great deal on his 11-volume diary.

Joanne Freeman: French was a congressional clerk. His job was to sit at the front of the House and record what was happening. But there were times when the fighting scared him and suggested to him that the Union was falling apart. I found around 120 fights, and there were countless others, but I only included the 70 or so that I could absolutely prove. Since I didn't want to tell the story purely chronologically, I needed a narrator to hold it together. French was later the commissioner of public buildings under Abraham Lincoln. He kept this diary for most of his life. It contains what he saw in Congress and what he thought about it. It's the kind of diary that a historian dreams of. And he was a newspaper man. He wrote a man-on-the-spot newspaper column. If I had created a character to be my eyewitness, it would've been this guy. He was the ideal narrator, not super important but amazingly observant and sensitive. He had a lot to say about everything.

Governing: And he becomes radicalized during the course of the book.

By the end of the book, he's radicalized. I needed to explain how a guy who at the beginning of the book was loved by everyone, who was unanimously selected as clerk, who had tried to make Southerners like him, ends up in 1860 going out to buy a gun in case he needed to shoot any Southerners. I had to get into the book how he went from point A to point B. That shows something - I call it the emotional logic of civil war - about how a civil war can make sense in some ways.

Joanne Freeman: The South was grounded on slavery, socially, economically, politically, personally. The idea of ending slavery in a way that was going to appease all of the economic and personal problems that this would cause was a problem in and of itself. Slavery was a way of life. If you're attacking slavery, you're attacking that way of life and an assumption about what America is. You're attacking an assumption about what the South is. French was from New Hampshire, and he went to visit plantations because he'd never seen one. He noted at first how the slaves were dressed well, like New Hampshire farm people. And he commented on one of the owners getting tearful over the death of an older slave. For a time French bought into the myth that slavery had created a civil way of life. This is hard to wrap your mind about today, but it shows the degree to which Southerners had taken it to be a big part of what America was to them. They created a myth.

Governing: How does this book address where we are today? What can we learn from your work on where we are?

Joanne Freeman: By telling the story of someone who begins wanting to hold everything together and ends wanting to shoot things to smithereens, the book looks at how a nation can be emotionally torn in two. It looks at how violence is not the absence of politics, but rather that violence is part of our politics and has been for a very long time. It highlights a mode of politics that we're seeing a lot of right now, the bullying and threatening. It’s not Bowie knives and guns, but you can look in Congress today and see this kind of behavior. You look at public rhetoric and see this behavior. You can see it in school board meetings.

The book shows some not very pleasant aspects of the American political tradition and gets at the heart of some of the emotional realities of what we're going through in this polarized time of extreme partisanship, where people reason or emote their way into doing different things. What we're looking at now is people trying to rouse other people to be angry. People trying to deploy anger to make them act politically. There are alarming ways in which we're standing today amidst the emotional and political realities of the book.

You can also hear more of Clay Jenkinson’s views on American history and the humanities on his long-running nationally syndicated public radio program and podcast, The Thomas Jefferson Hour. He is also a frequent contributor to the Governing podcast, The Future in Context. Clay’s most recent book, The Language of Cottonwoods: Essays on the Future of North Dakota, is available through Amazon, Barnes and Noble and your local independent book seller. Clay welcomes your comments and critiques of his essays and interviews. You can reach him directly by writing cjenkinson@governing.com or tweeting @ClayJenkinson.