Between these two omnibus legislative packages, the majority Democrats in Congress set out to appropriate something approaching 4 trillion dollars this fiscal year alone. The current national debt is $23 trillion, just six times the size of two specimens of recent congressional legislating.

The late Sen. Everett Dirksen (1896-1969) is credited with saying, “A billion here, a billion there, and pretty soon you're talking real money." That was then. Now it is a trillion here, a trillion there ... But who’s counting?

Loosening The Reins

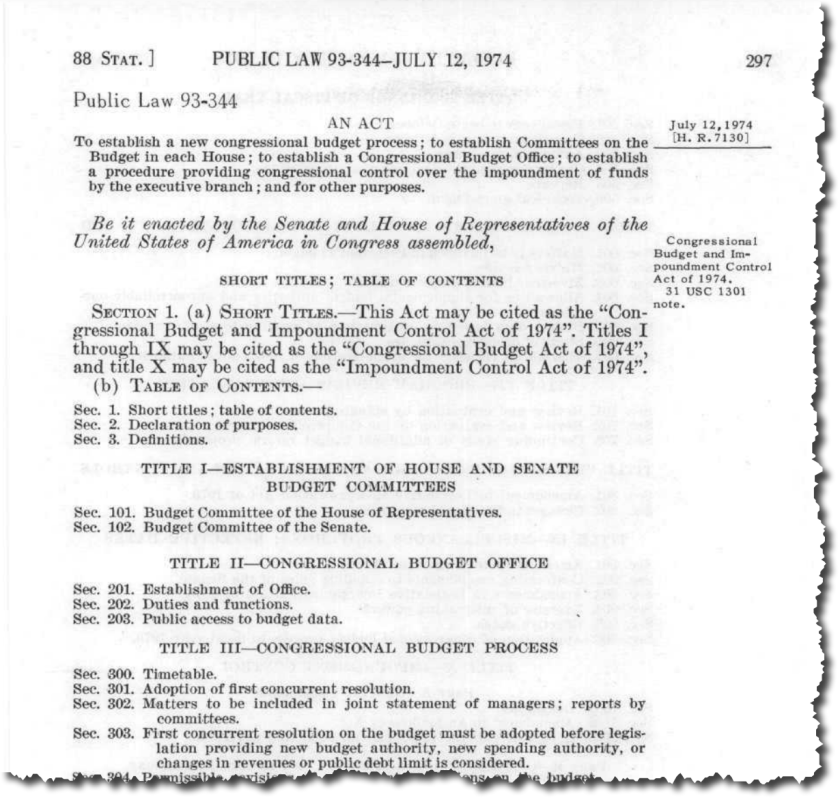

It may be that large, all-inclusive “omnibus” legislation is inevitable given the size and complexity of the United States in our time. If Congress had to debate every bridge or airport on the current list, it would take years to address the problem of American infrastructure. And yet we all know that some of the “infrastructure” spending now making its way through Congress will be on projects that probably could not stand the test of a focused debate. If it’s essential that 21st-century legislation be bundled under general headings, the question now is how swollen the bundle can become and still protect the American taxpayer from profligate spending or legislative provisions that have little or nothing to do with the stated purpose of the legislation.

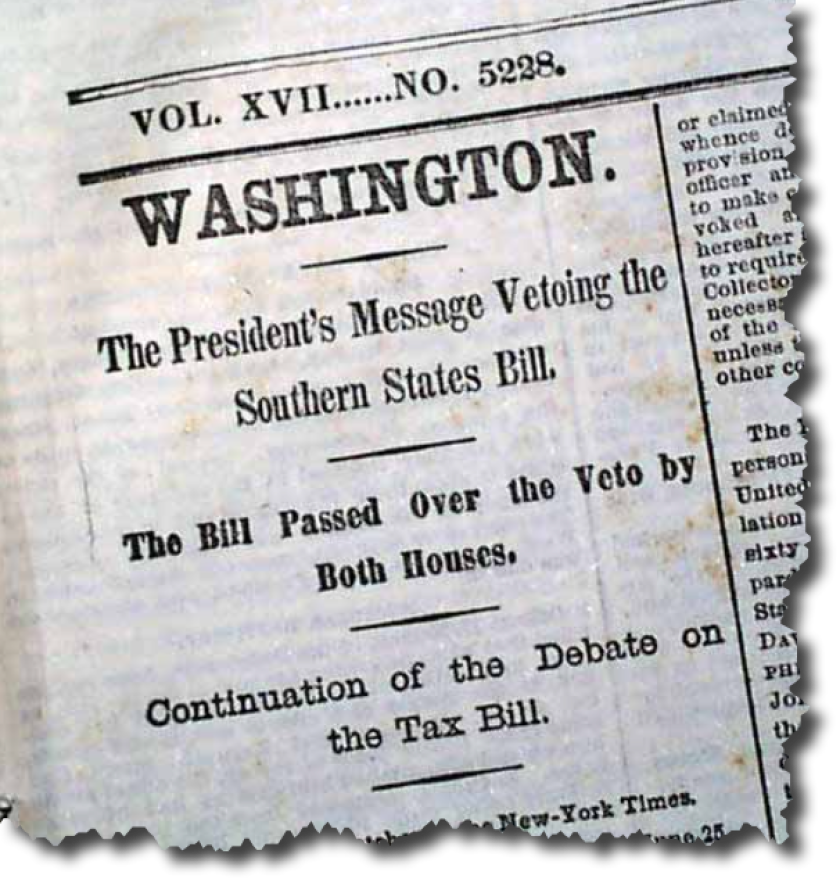

Once a bill has gone through Senate-House reconciliation so that its terms are identical, it moves on to the president, who can sign it or veto it or just let it pass into law without his signature. Because we have no line-item veto in our constitutional system, the president cannot remove the things he regards as unwise or unnecessary and keep the rest.

Battles of Presidential Will and Congressional Intent

Classic Infrastructure And Not So Skinny Bills

But the argument can be made — by the bill’s proponents — that each of these provisions relates in some way to the nation’s infrastructure or helps pay for the cost.

And that’s the “skinny bill!”

What began as the Build Back Better bill bundled a raft of progressive initiatives into one massive piece of legislation. Each component was so large and costly that it probably deserved to be debated and voted on separately. The bill stretched the definition of “infrastructure” almost beyond recognition. It would have, for example, expanded the Affordable Care Act, addressed global climate change in an ambitious manner, attempted immigration reform, provided for universal pre-kindergarten education, generous child-care subsidies, financial aid for college students, hearing aid benefits under Medicare, supported for low-income housing, and much more.

Thanks to nearly unanimous Republican opposition and the qualms of Democratic Sens. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, the bill is likely to be pared down, broken up and re-assembled before it passes the Senate, where it still has plenty of chances to die altogether.

Hanging Together or Hanging Separately

Omnibus legislation is not new. The Compromise of 1850 Act bundled five separate bills into one overarching piece of legislation. This included the Fugitive Slave Act that was anathema to most northern members of Congress. Omnibus bills brought two clusters of states into the union in the post-Civil War period.

Critics of the Build Back Better bill and the previous infrastructure bill argue that the Democrats are attempting to shovel into these massive bills their entire legislative agenda, and that while some of their proposals may be worthy of bipartisan support, the whole package offered in a take-it-or-leave-it manner forces Republicans to reject the bills both on principle and because they sincerely disagree with much of the Democrats’ agenda.

For their part, the Democrats argue — at least behind the scenes — that they have a narrow window of opportunity, and that they may have majorities in both houses of Congress for just one more year. Whatever they want to achieve by way of their agenda had better force its way through the House and Senate in one audacious initiative. Their assumption is that the country will be better for it in the long run, and nobody really stops to ask by what margin or just how the Social Security Act was passed into law in 1935.

Theodore Roosevelt’s Midnight Forests

The most interesting story in the history of omnibus spending bills involves President Theodore Roosevelt. In his seven years, 171 days as president, Roosevelt advanced his ambitious conservation agenda by any means he could. He read the National Monuments and Antiquities Act (1906) as broadly as possible. The act was designed to permit presidents to set aside small parcels to protect Anasazi villages or fragile archaeological sites from amateur pot hunters or commercialization. Think of Chaco Canyon or Canyon de Chelly. When Congress refused to make the Grand Canyon a national park (“not one cent for scenery,” said the speaker of the House), Roosevelt by executive order declared it a national monument instead. At 800,000 acres, it was approximately 799,000 acres larger than the intent of the National Monuments legislation. The Grand Canyon graduated to full national park status on Feb. 26, 1919. Roosevelt also invented the National Wildlife Refuge System by executive order in 1903, and he used the previously underused Forest Reserve Act of 1891 to set aside 150 million new acres of national forest. No president has done more to conserve and preserve the sublimities of the American West more than TR.

Not one cent for scenery.

Joseph Gurney Cannon, Speaker of the US House of Representatives, 1903-1911

The 16 Million-Acre Gambit

He knew that he had a 10-day interim before he must sign or veto the bill, so he called in his friend and U.S. Forester Gifford Pinchot and got to work. Before TR finally signed the offensive bill on March 4, 1907, he had created by executive order 21 new national forests in the six designated states and enlarged 11 others.

One less well-known feature of the Fulton amendment had a lasting impact. The amendment changed the name of the Forest “Reserves” to “National Forests” to make it clear that the public domain timber was meant to be harvested for use, not set aside to be protected from routine economic development.

Incidentally, Fulton failed to win re-election in 1908. He was a one-term senator.

As things stand today, we all know that if the tables were turned and a Republican majority in Congress were trying to dump a large number of not necessarily related initiatives into a single omnibus bill, the Democrats would cry foul and worry for the survival of the republic in apocalyptic terms. No wonder the American people are a little cynical about their government.

You can also hear more of Clay Jenkinson’s views on American history and the humanities on his long-running nationally syndicated public radio program and podcast, The Thomas Jefferson Hour. He is also a frequent contributor to the Governing podcast, The Future in Context. Clay’s most recent book, The Language of Cottonwoods: Essays on the Future of North Dakota, is available through Amazon, Barnes and Noble and your local independent book seller. Clay welcomes your comments and critiques of his essays and interviews. You can reach him directly by writing cjenkinson@governing.com or tweeting @ClayJenkinson.

Related Articles