Editor’s Note: This is another in an occasional series of articles Governing is publishing this year by Clay Jenkinson on some of the less well-known presidents of the United States.

(Saul Loeb/AFP/TNS)

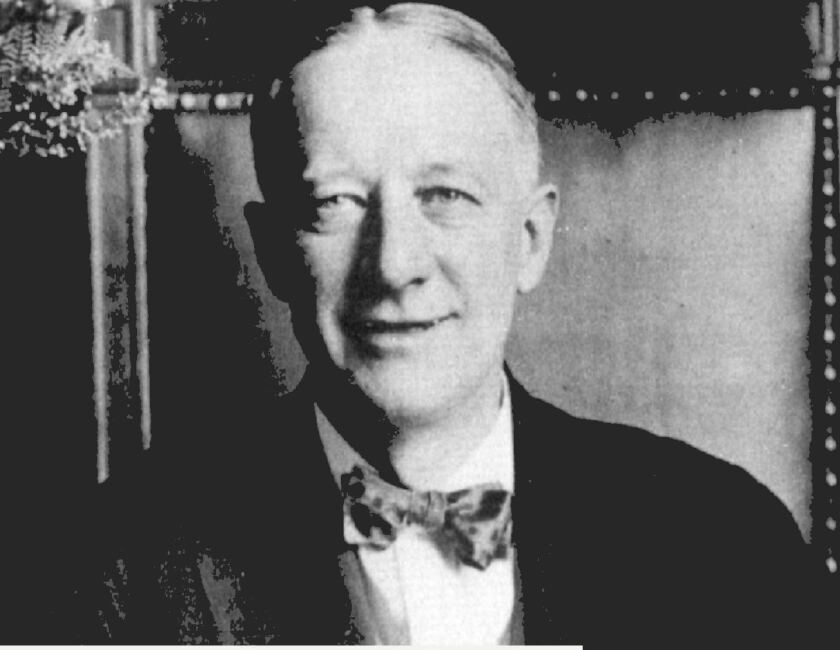

Hoover was the first Quaker president (the second was Nixon), the first born west of the Mississippi River (West Branch, Iowa), and the first to be orphaned in his childhood. He had never held an elective public office before he became the 31st president of the United States.

Stanford’s First Student

Hoover was one of the first graduates of Stanford University, founded in 1885. He studied geology. After he graduated in 1895, Hoover pursued his profession as a mining engineer in China, Australia and elsewhere. He said, “If a man has not made a million dollars by the time he is 40, he is not worth much.” This was hardly the statement of someone who would understand — in the 1930s — the plight of tens of millions of Americans for whom a million dollars was as remote as a flight to the moon, Americans who were just looking for a way to put a morsel of food on the table for their children.

Hoover and his wife Lou (who knew eight languages) both spoke fluent Mandarin. In fact, when they later wanted to have a private conversation in the White House, they sometimes used Mandarin rather than English.

Practical Help for People Who Needed It Most

After the war, he served as U.S. secretary of commerce in the Coolidge and Harding administrations.

The Great Humanitarian

By the mid-1920s he was an international hero, “The Great Humanitarian.” His rise to the American presidency had the feel of inevitability. When he ran in 1928 one of his slogans was “Who but Hoover?”

Al Smith was the first Roman Catholic to run for the presidency. This was at a time when there was widespread anti-Catholic sentiment in America. In fact, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) was as active in the South and Midwest terrorizing Catholics as African Americans. One reporter said Smith was defeated by the three Ps: Prohibition, Prejudice and Prosperity. One Protestant preacher said, “If you vote for Al Smith you’re voting against Christ, and you’ll be damned.”

The 31st President

Herbert Hoover proves that administrative mastery and capacity for rational analysis are not the same as good politics.

When he became president in 1929, Hoover warned about undo speculation in the stock market. But there was little he could do to dissuade the wildest wealth seekers at the end of the Roaring Twenties. Nevertheless, Hoover was optimistic about the general state of the American economy. He said, “Given a chance to go forward with the politics of the last eight years . . . we shall soon with the help of God be in sight of the day when poverty will be banished from this nation.” By the end of Hoover’s first year as president, the stock market had lost half of its value.

In 1932, 17,000 desperate WWI veterans descended on Washington, D.C., to demand their promised war bonus 13 years in advance. Thousands of veterans occupied federal buildings on Pennsylvania Avenue and camped on the Washington mall. President Hoover ordered the U.S. Army to clear the demonstrators out of the national capital. The armed response was commanded by Gen. Douglas MacArthur, who employed thousands of troops and six tanks to fulfill the president’s orders. Once he had forced the “Bonus Army” out of Washington, MacArthur burned their belongings and their shanties. The violence and highhandedness of MacArthur’s campaign sickened most Americans, who blamed Hoover for the cruelty of the government response to unambiguous human suffering, especially among men who had served their country in the war.

Hoover’s only answer to failed capitalism was … more capitalism. Between 1930 and 1932, 5,100 American banks failed. Eventually the number reached 9,000. There was, at the time, no federally guaranteed system of deposit insurance. (The FDIC was his successor’s creation.) Millions lost their life savings — some $3.2 billion, which was then a colossal number. Housing prices fell 67 percent. Industrial production dropped 46 percent. The food lines in every American city were a visual metaphor for national economic collapse.

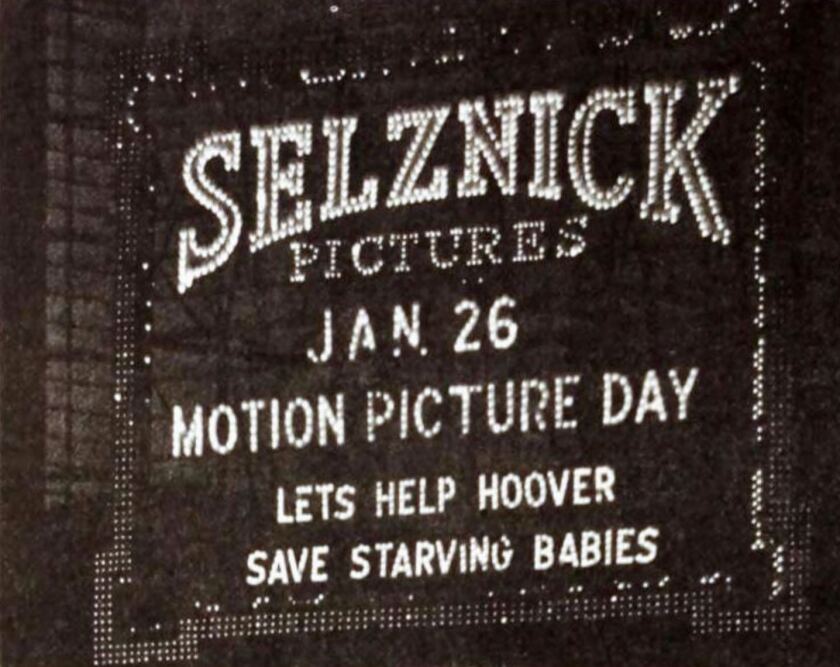

Hoover believed that private business not government should turn things around. Astonishingly, in 1930 Hoover told a delegation that came to the White House proposing a public works program, “Gentlemen, you have come 60 days too late. The depression is over.” The worst, by far, was yet to come. In his 1930 State of the Union address, Hoover said, “Economic depression cannot be cured by legislative action or executive pronouncement. Economic wounds must be healed by . . . the producers and consumers themselves.” Historian Robert Gruner has written, “He believed that government intervention, even to feed starving Americans during the worst economic crisis in the nation’s history, would mean surrendering to the European philosophy of paternalism and state socialism.”

Hoover’s reputation collapsed. The international hero of the 1920s now was nearly universally vilified for indifference and ineptitude. A joke of the time: Hoover asks Secretary of Treasury Mellon for a nickel to call a friend. Mellon replies, “Here, take a dime and call all your friends.”

The Coming of the New Deal

When Hoover finally did decide to use the federal government to provide relief, it was too little and too late, though some of his programs anticipated FDR’s New Deal.

With the coming of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (inaugurated March 4, 1933), the nature of the U.S. government changed forever. For better or worse, big government became a central fact of America life and the people of the United States began to look more often and more insistently to the federal government for support in difficult times. Although several major political figures have attempted to curtail or extinguish the New Deal, including Barry Goldwater, Newt Gingrich, Ronald Reagan, and members of the Tea Party and Freedom Caucus, government management of the lives of the American people has grown steadily since 1932 and, however heated the political backlash, continues to grow over time.

Underneath all the political debates of our time, including the 2023 debt-ceiling debate, this is the basic conflict: How much government assistance (intervention) is good for America and at what point does government largess disincentivize individual initiative and self-reliance?

FDR won in a landslide. He carried 42 states (Hoover six), won 472:59 in the Electoral College, and received 57.4 percent of the popular vote. It must have galled Hoover to be defeated for the presidency by Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who was widely regarded as a lazy, entitled playboy, whereas Hoover had achieved everything in his life by sheer dint of discipline and hard work. Here was a paradox. FDR was a spoiled patrician who became the presidency’s greatest champion of “the forgotten man.” Hoover was an orphan who embodied the American Dream at its quintessential form, and yet left office in something like disgrace.

Hoover spent the last 30 years of his life attempting to restore his reputation. He endowed the Hoover Institution at Stanford University in 1941. It was one of the country’s first great think tanks.

Why did Hoover’s presidency fail? Historian Stephen Graubard writes, “The answer, very simply, is that Hoover’s talent — an ability to organize for a specifically limited purpose — proved useless in a situation of unprecedented disorder created by the world economic Depression of the 1930s.”

Listen and subscribe to the audio version of this and other essays in the series from the Future in Context podcast using the player above or on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Stitcheror Audible. Clay welcomes your comments and critiques of his essays and interviews. You can follow his work and sign up for his newsletter at ltamerica.org.