Ratified in 1920, the 19th Amendment states that “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.” While the amendment allowed women the right to vote, it did not eliminate all voting restrictions, particularly those that impacted Black people and other minority populations.

Southern states in particular enacted laws to restrict the voting rights of Black men and women. In the early 20th century, many Southern states, including Georgia, established “white primaries” for the Democratic Party that forbade Black people from participating. Because the South was largely Democratic at the time, the winner of a Democratic primary was typically the general election winner. By prohibiting Black voters from participating in primaries, the Georgian government was effectively eliminating Black voting power.

But a unique 1946 election sparked political change. That year, Democratic House Rep. Robert Ramspeck of Georgia resigned, triggering a special election. Primary restrictions did not apply to special elections, meaning that Black constituents could vote for his replacement.

Mankin began her career as a lawyer, passing the state bar exam only four years after Georgia first allowed women to take the test. She opened a law office in Atlanta, working primarily with Black and low-income clients.

After serving as the women’s manager of a 1927 campaign for mayor, she decided to run for office herself. She was elected to the Georgia state legislature (known as the Georgia General Assembly) in 1936 and served five terms. Only the fifth woman to be elected to the General Assembly, Mankin advocated for liberal policies including improved teacher salaries and separation of juvenile inmates from adults in state prisons.

One of her political goals was to improve voting rights for Black and low-income voters. Mankin worked with liberal Gov. Ellis Arnall to repeal the Georgia poll tax in 1945, which disenfranchised many African Americans and other constituents who could not afford the voting fee.

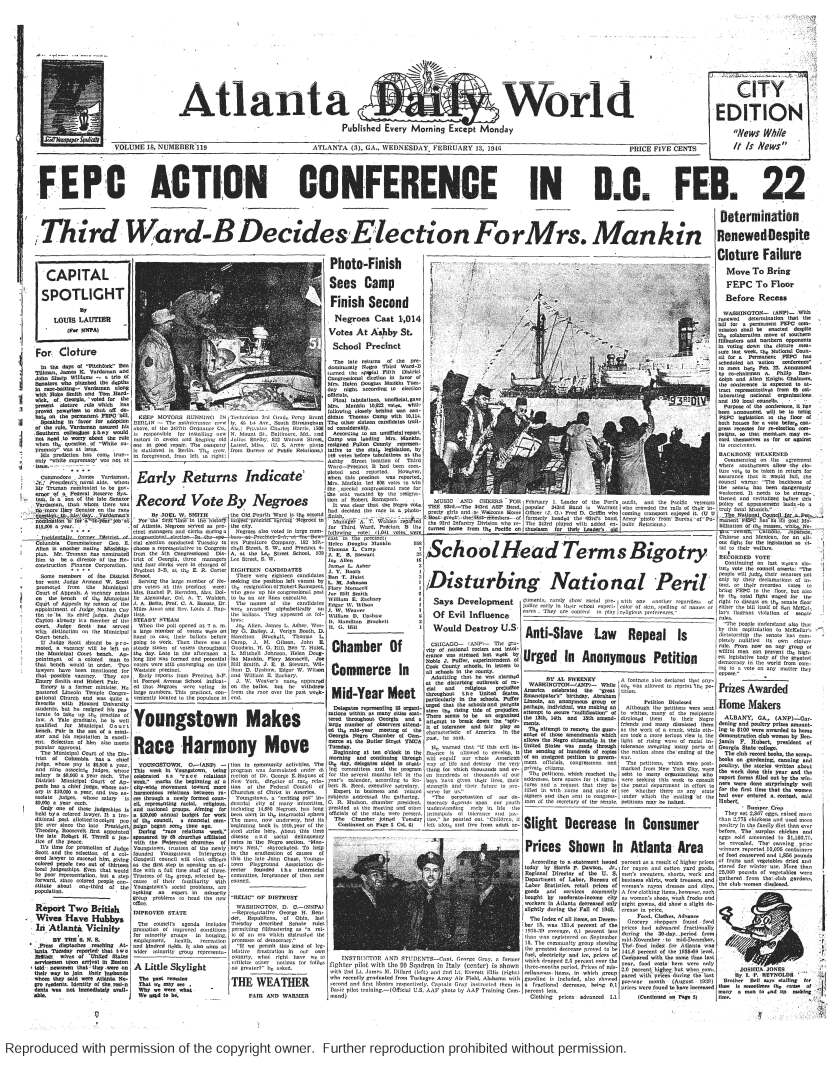

Black community leaders worked tirelessly to emphasize the importance of Black constituents voting in the special election. “It is important that we take advantage of every opportunity we have for exercising the ballot,” said Charles Lincoln Harper, president of the Atlanta branch of the NAACP, before the election. “Every citizen qualified to vote should go out of their way to cast his ballot.” According to the Atlanta Daily World, the oldest Black newspaper in the city, thousands of Black voters went to their county registrar’s office to qualify for the special election.

The success of both Mankin’s campaign and Black leaders’ advocacy became clear on election day. Mankin was narrowly behind frontrunner Thomas Camp until votes from precinct 3-B on Ashby Street came in. This largely Black ward swayed the election in her favor. According to the Atlanta Daily World, of the 1,014 votes cast in the neighborhood, 956 were for Mankin, who won the election in what the newspaper described as a “photo-finish.”

During her short congressional tenure, Mankin continued to advocate for equal voting rights, seeking a federal end to the poll tax. She promoted other liberal policies, including a federal housing program and price controls.

When she sought re-nomination the following year, her chances seemed promising. That year, the Supreme Court had deemed the Georgia white primary to be unconstitutional, meaning Blacks could vote in regular Democratic primaries. With Black voters on her side, Mankin was likely to win. But former governor and segregationist Eugene Talmadge was determined to remove Mankin from office and disenfranchise Black voters in the process.

Mockingly calling Mankin “The Belle of Ashby Street” (a name Mankin came to use with pride), Talmadge criticized “the spectacle of Atlanta Negroes sending a Congresswoman to Washington” and promised to “save Georgia for the white man.” To limit the power of Black voters, Talmadge and other state officials revived a county unit system of voting, which awarded a certain number of unit votes based on the popular vote each county received. Not used since 1932, the system gave more weight to votes from rural counties, while mitigating votes in urban counties, which included most Black voters.

Mankin fought the election results. She petitioned the U.S. District Court in Atlanta and then the U.S. Supreme Court, but both upheld the Georgia county unit system. Only in 1962, six years after Mankin’s death from a car accident, did the U.S. Supreme Court declare the system unconstitutional.

Mankin’s political loss, coupled with Gov. Talmadge’s white-supremacist policies, were a disheartening setback for Black Georgians. But her two campaigns also tell a story of how Black activism led to an increase in Black voter registration. Black leaders continued Mankin’s advocacy for equal voting rights, ultimately culminating in the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that outlawed racial discrimination in voting.

Looking back at the legacy of Mankin’s rise and fall from power, Durwood McAlister wrote in The Atlanta Journal that “Georgia politics haven’t been the same since.” As voting rights activists continue to fight against voter suppression and disenfranchisement, the full impact of this story may remain to be seen.