Thirty-five states gaveled open new legislative sessions last week. Many are making a point of how quickly they chose a speaker – the vote took all of 30 seconds in Washington state, for example.

That is in sharp contrast to the chaotic events in the U.S. House of Representatives a week earlier, which were a sad reminder of how fraught and flummoxed our national politics are, and almost certainly a harbinger of the reign of craziness we can expect in the Republican Party for at least the next two years.

(Kent Nishimura/Los Angeles Times/TNS)

(Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images/TNS)

History May Not Repeat Itself, But It Rhymes

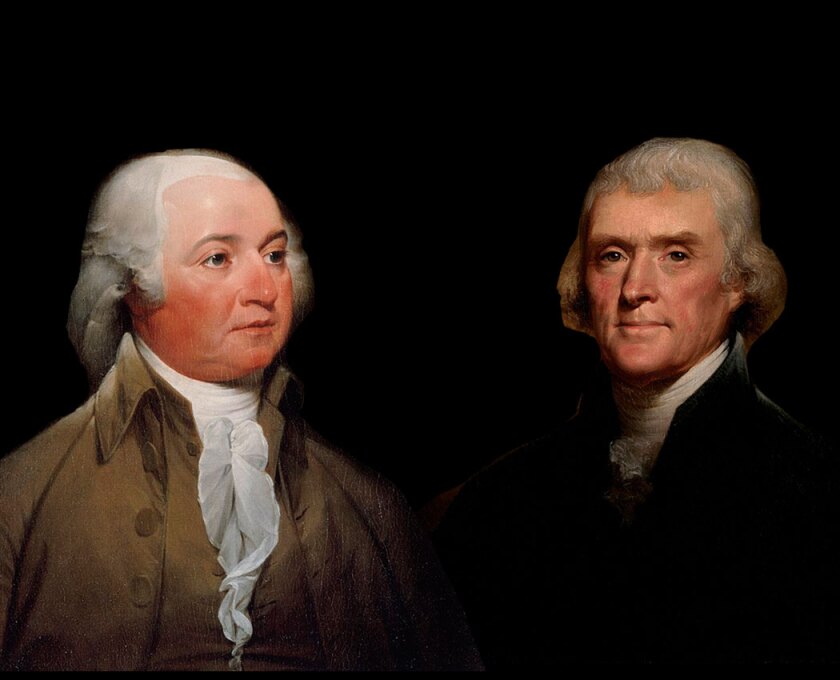

In some ways it is more useful and interesting to remind ourselves of what happened in the monumental presidential election of 1800, the first time in our history when power was transferred from one political party (the Federalists) to another (the Republicans).

Because of a flaw in the Constitution’s configuration of the Electoral College (repaired by the Twelfth Amendment in 1804), all the candidates were lumped together in 1800. Jefferson and his running mate Aaron Burr each got 73 electoral votes and though every American understood that Jefferson had been elected president and Burr vice president, the U.S. Constitution — blind to intention, fixated solely on results — recognized only a tie. Under provisions of Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution, this threw the election into the House of Representatives, where each of the 16 states got one vote. To make things even more interesting, the House that sat in judgment of Jefferson’s election in February 1801 was a lame-duck Federalist House. Thus, his enemies were in control of his fate.

Sound familiar?

Sound familiar?

The House of Representatives formally determined to sit in continuous session, without adjournments, until the issue was settled. Feb. 11, 1801, was a monumental day, during which 27 ballots were cast without producing the required nine-state majority. First ballot. Eight states for Jefferson, six for Aaron Burr, two states not counting because their delegates were evenly split. Second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh ballots, still 8:6:2. A few short breaks were taken through the rest of the night so that members could order in some food. Some napped. Some sent for bedding. Many slumped over their desks. By the end of this first long day, after 27 exhausting ballots had been taken and tallied with no shift in the results, the House agreed to recess from 3 a.m. to noon.

On Feb. 12, only a single ballot was cast. No change.

On Friday, Feb. 13, two more. Deadlock.

Saturday, Feb. 14, was Valentine’s Day, but there was no love in the American republic. Three more votes were taken. No change. The real drama of that day took place not in the House chamber, but out on Pennsylvania Avenue. On that muddy unfinished street, more than usually paralyzed by a freak D.C. snowstorm, President Adams and Jefferson ran into each other during their daily strolls (the new capital Washington was a very small town). Unfortunately, we have no transcript of the conversation between these two giants of the early national period, now mutually wary and mistrustful. Apparently, they discussed the crisis and Jefferson asked the president to issue some sort of a statement, public or behind the scenes, declaring that he would not tolerate any shenanigans with the certification. Adams refused to intervene. With a little pent-up Schadenfreude, he told Jefferson that he was heading home to Boston and he washed his hands of the entire business. He said the crisis could be resolved “by a word in an instant” if Jefferson declared that he “would not turn out the Federalist officers nor put down the navy, nor [ex]spunge the national debt.”

High Stakes

The stakes were so high that 30-year-old representative Joseph Hopper Nicholson of Maryland, gravely ill, had himself carried on a litter two miles to the Capitol to cast his vote(s) for Jefferson. Political strategists on both sides wondered whether the crisis would end in civil war. Republican Gov. Thomas McKean of Pennsylvania contemplated the use of force — a militia of up to 20,000 men — to arrest the conspirators and take back the government for Jefferson. Jefferson’s protégé James Monroe, now the governor of Virginia, began preparations for massing troops near the perimeter of the District of Columbia, to take back the government by force if necessary. Several states, including Vermont, warned that they might secede if the Federalist coup succeeded. How close we came to the collapse of the American republic just a little more than a dozen years into its existence is unclear. In retrospect, since we know how things turned out, we underestimate how close we came to national catastrophe.

Breaking the Deadlock

At some point it became clear that the Jefferson camp was never going to give up. His Federalist enemies could keep him from being president indefinitely, but they could never secure enough votes to make Aaron Burr president. Eventually the Federalists decided that they would let Jefferson be elected, if he would make some critical concessions. First, he must agree not to remove all Federalist officeholders from their posts. No wholesale sweep. It was understood that he would remove some Federalist officeholders — even the Federalists acknowledged that a president is entitled to surround himself with individuals of his own political stamp — but they demanded that Jefferson keep a substantial percentage of the existing bureaucracy. This demand actually harmonized with Jefferson’s own political philosophy.

Second, the Federalists insisted that Jefferson must agree not to dismantle Alexander Hamilton’s fiscal system. Jefferson was known to be a severe critic of Hamilton’s funding schemes, his national bank and the national debt, which he regarded as a tax on the unborn. He had fought it within the cabinet of Washington, both on constitutional and policy grounds. Some of the extreme Federalists believed that Jefferson might actually just cancel the national debt.

Whether Jefferson or Jefferson’s closest allies ever made these key concessions is unclear. We know that several intermediaries had conversations with Jefferson during this period. Moderate Federalist James Bayard, the sole representative from little Delaware, got enough assurances from the Jefferson circle — with emphasis on the Federalist officeholders — that he decided to make the case for certifying Jefferson on Monday, Feb. 16. The blowback from die-hard Federalists was deafening. “The clamor was prodigious,” he later reported, and “the reproaches vehement. Some [Federalists] were appeased; others furious, and we broke up in confusion.”

Sound familiar?

Both Monday ballots confirmed the deadlock: 8:6:2.

Finally, on Tuesday, Feb. 17, on the 36th ballot, the Federalists capitulated. Exhaustion probably played as large a role as the realization that they could not break the solidarity of the Republican caucus. Anti-Jefferson representatives of the Maryland and Vermont delegations agreed not to vote, which gave the Jeffersonians the majority in those state delegations. Thus, Jefferson finally won the 1800 presidential election 10:4.

Jefferson went to his grave insisting no bargain had been made with the Federalists to obtain the presidency. He declared that he would “never go into the office of President ... with my hands tied by any conditions which should hinder me from pursuing the measures” the country needed. This may be true, but it seems clear to most historians that a few very careful conversations occurred behind the scenes which provided the needed assurance to the Federalists and yet left Jefferson in possession of his integrity, his personal refusal to negotiate to obtain the office to which had been unquestionably elected by the American people.

Jefferson served two terms as president. He was resoundingly re-elected in 1804. He made no attempt to dismantle the Hamilton fiscal system, though he chastened it somewhat, and did everything he could to retire the national debt, devoting 73 percent of U.S. government revenues to debt retirement! He removed some of the Federalist die-hards, but generally speaking, he allowed normal attrition (retirement and death) to clear the path for Republican appointments. Jefferson had very little sense of humor, but he did manage to quip that filling federal offices should be called “Appointments and Disappointments.”

When the air cleared, Washington observer Margaret Bayard Smith expressed her sense of relief. “The dark and threatening cloud that had hung over the political horizon rolled harmlessly away,” she wrote, “and the sunshine of prosperity and gladness broke forth.”

Whether anyone will be able to sum up the events of the last couple of weeks and the last few years with the words “rolled harmlessly away,” is very far from certain. Stay tuned.