Activists first developed a National Day of Mourning in 1970. That year, Massachusetts Gov. Francis Sargent invited Wampanoag leader Wamsutta Frank James to speak at a state dinner marking the 350th anniversary of the arrival of the Pilgrims to what became Plymouth Colony. After insisting on reviewing James’ speech before the dinner, the state public relations team refused to let James convey his original message on the abuses of Pilgrims toward Native Americans. Instead, they gave him a revised, sanitized speech that they insisted he read.

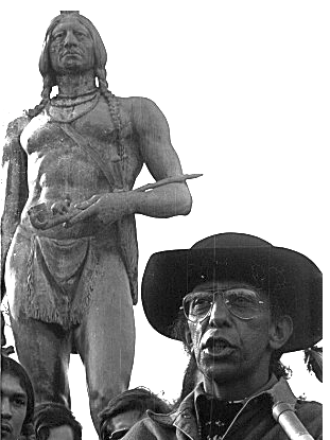

James refused to attend the dinner and read the revised speech. In protest, he and other Native American leaders in the New England region put together an event to address the contemporary and historical injustices faced by Native Americans at the hands of European colonists and their descendants. On Thanksgiving Day 1970, James and other activists staged a protest in Plymouth, Mass., the site of the original Plymouth Colony. Standing next to a statue of Ousamequin (also known as Massasoit), the 17th-century leader of the Wampanoag people, James read his original speech for the state dinner.

"We, the Wampanoag, welcomed you, the white man, with open arms, little knowing that it was the beginning of the end; that before 50 years were to pass, the Wampanoag would no longer be a free people,” said James.

This protest marked the first National Day of Mourning, a now-annual event. Organized by the Native American activist group United American Indians of New England (UAINE), the day typically includes a march through downtown Plymouth, along with a rally and speeches at the site of James’ 1970 speech.

By choosing to hold the National Day of Mourning on Thanksgiving Day, UAINE seeks to dispel common American myths about the relationship between Native Americans and European colonists. Rather than a story of cooperation and unity, as is often told on Thanksgiving, the National Day of Mourning offers a narrative that recognizes the injustices faced by Native Americans at the hands of white people.

According to UAINE, the day is one of “remembrance and spiritual connection, as well as a protest against the racism and oppression that Indigenous people continue to experience worldwide.”

While UAINE has successfully hosted marches and speeches for this event for over 50 years, they have had multiple clashes with the town of Plymouth. In 1997, nearly 25 protestors were arrested by Plymouth police for marching through the center of the historic town without a permit. UAINE argued that no permit was needed because the land was originally their ancestors’.

These arrests resulted in a small but real victory for UAINE. Ultimately, all charges were dropped against the arrested protestors. UAINE was allowed to march annually through Plymouth without a permit, and the town even installed a plaque to officially recognize the National Day of Mourning.

“Many Native Americans do not celebrate the arrival of the Pilgrims and other European settlers,” the plaque reads. “To them, Thanksgiving Day is a reminder of the genocide of millions of their people, the theft of their lands, and the relentless assault on their culture.”

The creation of the National Day of Mourning in 1970 coincided with growing activism among identity groups -- women, African Americans, gay and lesbian people, ethnic communities and others – all vocally advocating for equal rights and representation in American government and society.

In 1975, a Native American organization on the West Coast put on an event similar to National Day of Mourning. Unthanksgiving Day, also held annually on Thanksgiving, honors the histories of Native Americans since the arrival of European colonists (this event also commemorates the occupation of Alcatraz by Native American activists beginning in 1969).

The National Day of Mourning is part of a growing movement toward rethinking national holidays. In 2021, President Biden became the first president to officially recognize Indigenous Peoples Day, a day honoring Native American culture and recognizing the injustices done to Native Americans in the past and present. Held on Columbus Day each year, the holiday counters the white-washed celebration of European colonial history that Columbus Day represents to many.

“What has happened cannot be changed,” James explained at Plymouth in 1970. “But today we must work towards a more humane America.” James’ sentiments over 50 years ago in many ways embody the efforts of the UAINE and other activist groups to recognize history in order to improve the present.