Talking About Race

Second, DiAngelo is right: White people have a really hard time talking about racism in the abstract and our own racism in particular. We like to think of ourselves as enlightened, decent and color blind. And we recoil in indignation and high dudgeon when we are told we are racist, no matter how sweetly. In any conversation on this topic, you are sure to hear one or more people say, “I don’t have a racist bone in my body.” Which is an essentially meaningless statement. It’s not so much about what you consciously think or say about Black people, or Native Americans, or Hispanics, or the LGBTQ community; it’s about deeply embedded patterns of mind that are difficult to recognize and even more difficult to confront.

The Time Is Overdue

As I write these words, I know that some of my readers will reject what I am saying. They will deny that America is, in 2021, fertile ground for racism. They will not only deny that they are capable of racism, but strenuously dispute the very concept of structural or systemic racism. They will acknowledge the legacy of slavery and racial discrimination in American history, but argue, in effect, that “that was then and this is now,” or declare that whatever was true of white America in 1890 or even 1957 does not make them complicit, because their forebears came directly from Germany or Ireland or Norway to take up homesteads in Iowa or Nebraska, and never owned a slave, perhaps never met an African American. They will say that the playing field is now more or less level and that the future success of minority communities will depend on how well they pull themselves up by their own bootstraps. (All of these arguments, or dodges, are covered in chapter one of DiAngelo’s White Fragility.) They are important challenges to wrestle with alone and in community, but they are an argument for the status quo, and every cultural marker reminds us that it is too late for the status quo.

How Racism Works In America

Let’s just look at a few examples of how racial bias works in America.

America’s Daughter And The Other “Others”

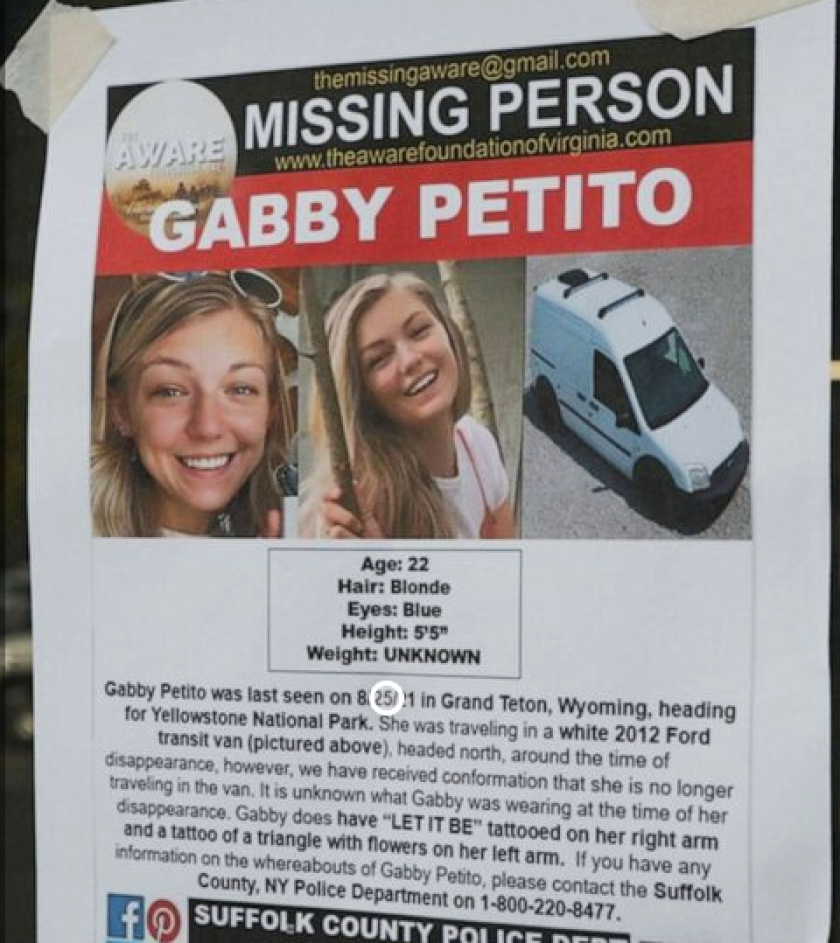

Why did the Gabby Petito story go viral? Well, she was young, bubbly, attractive, adventurous and innocent, posting cheery you-are-there video snippets on her social media accounts and posing for photographs in all the usual ways in places like Arches National Park.

And she was white.

A white girl goes missing on a cross-country vacation and she gets greater national attention than a SpaceX launch. And yet in that same Wyoming where Petito's body was found on Sept. 19, 2021, more than 700 Native Americans, mostly women and girls, have disappeared in the decade between 2010 and 2020, according to a report by Wyoming's Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons Task Force. Where was Anderson Cooper then? Not one of these stories got national attention. Google Gabby Petito and you will find a dozen intricate timelines of the last months and days of her life, as if we were collectively following the escape route of John Wilkes Booth in 1865 or the road to the Little Bighorn in 1876.

Alex Piquero, a criminology professor at Monash University and sociology professor at the University of Miami said, “There are a lot of women of color, and especially immigrants, this happens to all the time, and we never hear about it.” What if Gabby had been Black, or Latino, or Native American? Would that story have caused the entire national media establishment to hurl production teams into the outback of Wyoming, with CNN reporter Randi Kaye on location trying to determine if Brian and Gabby parked their van at this primitive turnoff in the national forest or on a nearly identical spot a few hundred yards down the road? Tens of thousands of young people disappear every year. Very few, as USA Today reporter Suzette Hackney put it, “receive the national spotlight that seems reserved for white women and white girls.”

Northern Arapaho missing persons advocate Lynnette Grey Bull said, “It's kind of heart-wrenching, when we look at a white woman who goes missing and is able to get so much immediate attention. It should be the same, if an African American person goes missing, or a Hispanic person goes missing, a Native American ... we should have the same type of equal efforts that are being done in these cases.” Maybe if she had been Miss Indian America she might have received some coverage or if she were an African American Olympic gold medalist.

Our Disquieting Moment

Be it resolved: "The American Dream is at the Expense of the American Negro" - a 1965 debate between James Baldwin and William F. Buckley still resonates today.

This is all deeply disquieting. I would not have been capable of seeing the race differential in these stories had I not done the hard, and not always pleasant, reading that is now available to all Americans. We have to hope that James Baldwin was wrong in 1968 when he wrote, “I will flatly say that the bulk of this country’s white population impresses me . . . as being beyond any conceivable hope of moral rehabilitation. They have been white, if I may so put it, too long; they have been married to the lie of white supremacy too long.”

You can also hear more of Clay Jenkinson’s views on American history and the humanities on his long-running nationally syndicated public radio program and podcast, The Thomas Jefferson Hour. He is also a frequent contributor to the Governing podcast, The Future in Context. Clay’s most recent book, The Language of Cottonwoods: Essays on the Future of North Dakota, is available through Amazon, Barnes and Noble and your local independent book seller. Clay welcomes your comments and critiques of his essays and interviews. You can reach him directly by writing cjenkinson@governing.com or tweeting @ClayJenkinson.