A Little History First

The Electoral College emerged from the 1787 Constitutional Convention as a late-in-the-game political compromise that nobody embraced with wholehearted joy, but which seemed at the time to be the only mechanism for selecting the president that was not deeply objectionable to some faction or other of the Founding Fathers.The “Father of the Constitution” James Madison had spent most of his time before the Founders gathered in Philadelphia in May 1787 trying to imagine a truly national government that would replace the loose confederacy of the Articles of Confederation. His principal goals at the Convention were to replace not repair the Articles, with a new national government consisting of three separate branches — legislative, executive, and judicial — and to make it much harder for individual states to impede the work of the nation at large.

He knew there would have to be an executive in the new system, but in the months before the convention he hadn’t given that officer much thought. The Virginia Plan (really the Madison plan) called for the executive to be chosen by the national legislature to serve a term of six or seven years and not to be eligible for re-election. That’s as far as Madison got before the convention debates began.

James Madison, the "Father of the Constitution."

Madison’s only true rival at the Convention for a deep understanding of the history of republics, James Wilson of Pennsylvania, believed that the executive should be chosen by direct election of the people (i.e., white males of a certain property base). But he was essentially alone in that commitment to a popularly chosen president. In other words, the idea of direct popular election of the President of the United States, now supported and expected by most Americans, had few takers among the Founding Fathers. Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts argued strenuously against direct election of the president because the people were, he insisted, “radically vicious” and “ignorant.” Virginia’s George Mason, the celebrated author of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, said you may as well ask a blind man to select colors as permit the people to choose their own first magistrate. Wilson’s proposal was soundly defeated nine to one (each state had one vote, several not attending or not voting).

Most of the delegates in Philadelphia believed the executive should be chosen either by the national legislature itself or by the several state legislatures. Both of those proposals had seemingly insuperable problems. If Congress chose the president, he (or now she) would be too dependent on the legislative branch. This would violate Montesquieu’s principle of separation of powers, checks and balances. On the other hand, if the states selected the president, the national government would not have sufficient authority or stature to overcome the fatal weakness of the Articles of Confederation, which was essentially a very limited compact of sovereign states. Madison and the other nationalists wanted to reduce the power of the states severely. William Patterson of New Jersey and the small state advocates wanted to make a few changes in the Articles of Confederation to fix problems involving revenue, trade, and enforcement of national laws, but to maintain as much state sovereignty as possible.

The debate over the precise nature of a national executive, how he should be chosen, the number of years he should serve, what his powers should be, whether he should be eligible or ineligible for re-election, to whom he should be accountable, and how he could be removed if necessary, occupied a great deal of time over the course of the summer of 1787, without any real consensus emerging. The Founders (except for the outlier Alexander Hamilton) were sure they did not want a king, but they found it difficult to envision an executive who had sufficient authority and autonomy to be effective but without so much power that he might become a despot and re-create the oppressions that led to the American Revolution in the first place.

Eventually, the Founders decided that the chief executive should be elected by the people, not the states or the national legislature, but not by direct popular vote. This would make the president independent of the legislative branch. Because they had a hand in the presidential election, the people would feel greater confidence in their government and begin to direct their focus to the national government rather than to their state capitals. The founders decided the president should be eligible for re-election, but his term should be relatively short so that bad presidents would not be in office long enough to do any lasting mischief. Earlier in the summer, Luther Martin of Maryland and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts had called for presidential terms of eleven years and even 25, and the high-toned Hamilton had called for the president to serve for life. But that was Hamilton.

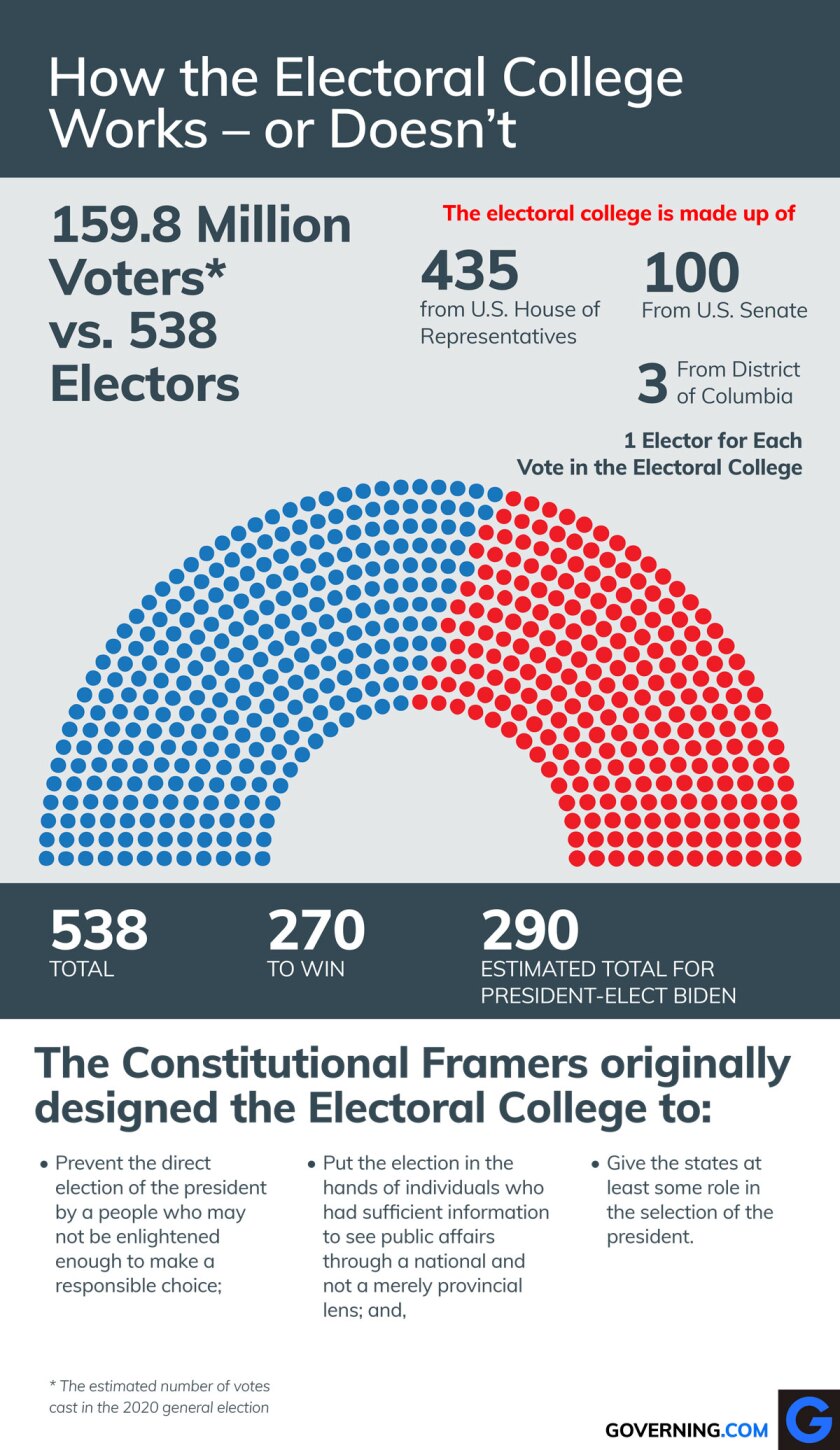

Eventually, the idea of an Electoral College emerged from this protracted and unsystematic debate. As originally designed — if the Convention debates are a guide — the Electoral College was designed to do three things. First, it would prevent the direct election of the president by a people who may not be enlightened enough to make a responsible choice. Second, it would put the election in the hands of individuals who had sufficient information to see public affairs through a national and not a merely provincial lens. The thought was that the country was so vast (already) that most citizens would simply not be able to keep up with national affairs. National affairs should be left to those who were tied to the continental information network, such as it was at a time when communications were slow and highly inefficient, and most people lived out their lives without significant access to good newspapers. Third, it would give the states at least some role in the selection of the president.

Democracy – Too Much Then, Too Little Now

The Founders were, on the whole, frightened of too much democracy, which they often called “mobocracy,” because they didn’t really believe that the people were responsible or well-informed enough to elect their own executive without some supervision by more enlightened individuals. Two hundred thirty years later, we are more concerned with too little democracy, not too much. The American people have been directly electing their House representatives from the beginning, along with local and state officials, including governors (i.e., the state executive) and since 1913 they have been directly electing their U.S. senators, too. The concern of the Founders about the problem of the vast geography of America — that it would be impossible at the far edges of the republic for the people to be sufficiently familiar with national political candidates — has been long since overcome by our communications infrastructure. Today, even moderately attentive citizens know an enormous amount about their presidential candidates thanks to television, social media and the Internet.The Committee of Unfinished Parts

The method of electing the president was a source of such mutual confusion and dispute that the final protocols were not crafted until very late in the process, and then by something humbly called the Committee of Unfinished Parts. The committee formulated a compromise between the small state suggestion that each state have equal representation among the electors and the large state insistence that bigger, more populous states that contributed more to the GDP have greater weight in choosing the president. The committee decided that a state’s electors would consist of the number of its House members (proportional) plus the number of its senators (equal representation). Thus today North Dakota with the mandatory minimum of one U.S. Congressman gets three electoral votes, and California with 53 Congressmen and women gets 55 electoral votes. This compromise gives small states like Wyoming and Vermont a little more weight in presidential elections. Without that extra weight among the least populated (usually Red) states, Hillary Clinton would have won the 2016 election.Before the Civil War, the electoral formula (number of representatives plus two) gave the slave states a considerable added advantage in presidential elections, because they were able to count every five slaves as three for the purposes of Congressional apportionment. The infamous Three Fifths Clause rewarded slave states with more power in Congress and in presidential elections. That is why a distinguished American historian, Garry Woods, was able to entitle his book on Jefferson’s election “Negro President:” Jefferson and the Slave Power. Even today the Electoral College has the effect of under-representing African Americans and other minorities, by giving predominantly white states like Montana and Utah more power than they would have under a more democratic arrangement.

According to the Founders’ formula, the electors would cast their votes in their home states, not in the nation’s capital. This was partly a reflection of how expensive and inconvenient it would be for these temporary electors to travel all the way to the national capital for the sole purpose of casting presidential votes, but it was also intended to prevent what the Founders called a “cabal” of electors scheming and horse trading in a closed room far from home (think of the College of Cardinals in Roman Catholicism).

A Fossil That Has Become a Real National Problem

So, if we are now much more comfortable with democracy than the 55 white, privileged, mostly conservative men we call the Founding Fathers, and the spread of meaningful information about candidates is no longer an issue, why do we cling to the Electoral College? The main answer is simple enough: because it’s there, enshrined in the Constitution, and getting rid of it would require a constitutional amendment, and that is nearly impossible. The Constitution has been amended only 27 times in its 230-year history. If you subtract the first ten amendments (the Bill of Rights), which were essentially an immediate addendum to the Constitution (ratified Dec. 15, 1791), that means that America’s fundamental charter has only been amended 17 times in well more than 200 years. That’s one amendment approximately every 12 years. The last successful amendment, ratified 28 years ago in 1992, was of no great significance. It merely prohibited members of Congress from raising their own salaries. At the time, that seemed very important.Procedurally, the most important of the post Bill of Rights amendments was the Seventeenth Amendment, which provided for direct election of U.S. senators. It was ratified in 1913. Previously, senators had been selected by state legislatures. Thus, the Seventeenth Amendment represents a potentially useful precedent for moving from strict state-based control of the national government to a more direct involvement by the citizens of the United States.

To amend the Constitution, you must engineer a two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress, and then get three quarters of the states (38 states) to ratify it. The Founders set the bar high so that the Constitution would not be changed for what Jefferson called “light and transient causes,” but they may have set it too high, given how few substantive amendments have been promulgated and ratified. The citizens of the United States can also call for a constitutional convention to make reforms and amendments, but it has never been successfully triggered by the resolutions of two-thirds of the state legislatures.

Even though in recent polls somewhere between 60 and 70 percent of the American people favor the elimination of the Electoral College, it’s hard to imagine how such an amendment would survive Congressional scrutiny or the ratification process. Given the fact that the Democrats have won the popular vote in seven of the last eight presidential elections, it is exceedingly unlikely that Republicans would be willing to eliminate the Electoral College and support the direct election of the president. In fact, unless the Republican Party expands the size of its cultural and demographic embrace, it’s hard to imagine it winning future presidential elections without the boost that the Electoral College gives to low-population conservative states.

Although Mr. Trump made some inroads with African Americans and Hispanics in the recent election, the changing demographics of America would seem to favor the Democrats by increasing popular majorities in the decades ahead. In other words, the Republican Party (as it now configures itself) needs the Electoral College to thwart or diminish the popular will, if the tally of the national popular vote accurately reflects that will.

Nor are the less populous states likely to welcome the elimination of the Electoral College. They would lose what little electoral advantage they have in a direct presidential election. North Dakota is already almost statistically negligible in presidential elections. It would become a nullity in the absence of the Electoral College. The continuing importance of small states under the current system was seen in President Trump’s late-campaign visit to Omaha, Nebraska. Nebraska (and Maine) award electoral votes by Congressional district rather than in the winner-take-all system used in all other states. Mr. Trump knew that if the election were extremely tight, he might need that single electoral vote of Nebraska’s second Congressional district. Without an Electoral College he would not have wasted precious late-campaign time in lowly Nebraska, with its population of just under two million.

Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by almost three million in 2016, yet she lost decisively in the Electoral College. The discrepancy struck many as problematic and anti-democratic, but most people nevertheless understood that our national bylaws operate in this eccentric way. But what if she had won by 8 million or 13 million popular votes and still lost the election? At some point the difference becomes unacceptable (as it was then for some).

Legitimacy Matters

The biggest issue with this differential is that it creates a legitimacy problem for the winner. Naturally, every presidential candidate wants to win the popular vote. To lose that vote in a society as committed to participatory democracy as the United States, even if the Electoral College brings victory, is to suggest that the winner is not really the people’s choice for president. That is surely one reason why Donald Trump insisted after the 2016 election that he had actually won the popular vote, too, and that the seeming preference for Mrs. Clinton was the result of election fraud and chicanery.When the winner gets a plurality both in the popular vote and in the Electoral College, the Electoral College provides an additional stamp of credibility and finality to the election. If Mr. Trump had won the 2020 election, but Joe Biden received five million more votes, the Democrats would have howled in protest, and from the point of view of popular democracy they would have been right. Legitimacy matters. We have a problem, what appears to be a growing problem, and we will have to fix it. In an era when a president-elect’s legitimacy is now routinely challenged for other reasons (think birtherism or Bush v. Gore), the Electoral College is a potentially dangerous drag on America’s capacity to govern itself.

The main original purpose of the Electoral College was abandoned decades ago. The Founders' idea was that wise and sober electors would have considerable discretion in determining the next president. They would not be bound by the results of the election. If the people appeared to be electing a scoundrel or a demagogue (think of Aaron Burr then or David Duke now), the electors could select a more respectable individual instead.

The purpose of the Electoral College, said Alexander Hamilton in the Federalist Papers, was to ensure “that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications.” The Constitution itself provides no instructions about how each state’s presidential electors should be chosen or how they should vote once empaneled. As they were originally constituted, they had complete freedom to name a president of their choice, though it was expected that in almost every case the electors would vote for the winner of the election in their state. In the course of the 20th century, most states passed laws requiring the electors to cast their votes for the winner in that state. These are known as faithless elector laws. After questionable faithless elector activity in Colorado and Washington State in 2016, the U.S. Supreme court ruled unanimously in Chiafalo v. Washington and Colorado Department of State v. Baca that states may enforce laws to punish faithless electors.

Attempts to Avoid Another Constitution Amendment

Some opponents of the Electoral College have proposed a range of legislative workarounds that would not require a constitution amendment. One proposal is to increase the size of the House of Representatives by 100, to 535, allocating the new seats to the most populous states. This would lessen the influence of sparsely populated states and make the Electoral College results resonate better with the national popular vote. Another proposal is called the National Interstate Popular Vote Compact. This would require the electors in every state to vote for the winner of the national popular vote. This is essentially a way of certifying the national popular vote (intended result, no amendment necessary), but it would be fiercely resisted by many states and it might not survive a Supreme Court challenge. Why should Kansas have to cast its six electoral votes for a presidential candidate who lost by a 60:40 popular vote in the state? That would seem to defeat the purpose of the Electoral College altogether. So far 16 states with electoral votes totaling 196 have approved the compact. To take effect it would have to be approved by states with electoral votes totaling 270. Not likely, I think.Thomas Jefferson understood more than anyone else in the founding generation the problem of the fossilization of constitutional provisions that have outlived their usefulness or fairness. In a letter to Virginia lawyer and writer Samuel Kercheval dated July 12, 1816, Jefferson famously wrote:

Some men look at constitutions with sanctimonious reverence, and deem them like the arc of the covenant, too sacred to be touched. They ascribe to the men of the preceding age a wisdom more than human and suppose what they did to be beyond amendment. I knew that age well; I belonged to it and labored with it. It deserved well of its country. It was very like the present, but without the experience of the present; and forty years of experience in government is worth a century of book-reading. … I am certainly not an advocate for frequent and untried changes in laws and constitutions. I think moderate imperfections had better be borne with; because, when once known, we accommodate ourselves to them, and find practical means of correcting their ill effects. But I know also, that laws and institutions must go hand in hand with the progress of the human mind. As that becomes more developed, more enlightened, as new discoveries are made, new truths disclosed, and manners and opinions change with the change of circumstances, institutions must advance also, and keep pace with the times. We might as well require a man to wear still the coat which fitted him when a boy, as civilized society to remain ever under the regimen of their barbarous ancestors.

We are, in Jefferson’s formulation, trying “to wear still the coat which fitted” us when we were a child among nations. But finding a way to let our constitution “keep pace with the times” is proving to be a very difficult problem.

For more of Clay Jenkinson's views on American history and the humanities, listen to his weekly nationally syndicated public radio program and podcast, The Thomas Jefferson Hour. Clay's most recent book Repairing Jefferson's America: A Guide to Civility and Enlightened Citizenship is available on Amazon.com.