It’s the tendency of Americans, suggests historian and bestselling author H. W. Brands, to simplify the past, when in truth our history is every bit as complicated and divisive as the present. Working to shine light on overlooked complexities, Brands probes the intersections of individual lives and narratives — what he calls “little history” — with the overarching accounts of “big history.”

With Our First Civil War, the big history is the American Revolutionary War and the little histories are the compelling stories of individuals forced to choose between forsaking their country and taking up arms, or remaining loyal to the British throne. In the end, Brands emerges from this retreat into the past with both “good news and bad news” for present day America. Brands recently spoke with Governing.com Editor-at-Large Clay Jenkinson. The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Governing: What led you to write Our First Civil War?

H. W. Brands: History is always more complicated than we think. We’re aware of the one-line description of the American Revolution, where the Americans get fed up with the British, declare independence, and win the war. But it’s not as simple as that. People go to the past looking for simple answers that will support their preconceptions. I try to show that life in the past was just as complicated as life today. That makes it all the more interesting. The more layers to peel off, the better.

What causes a person to forsake his country and take up arms against it?

(@hwbrands)

Rejecting the Status Quo

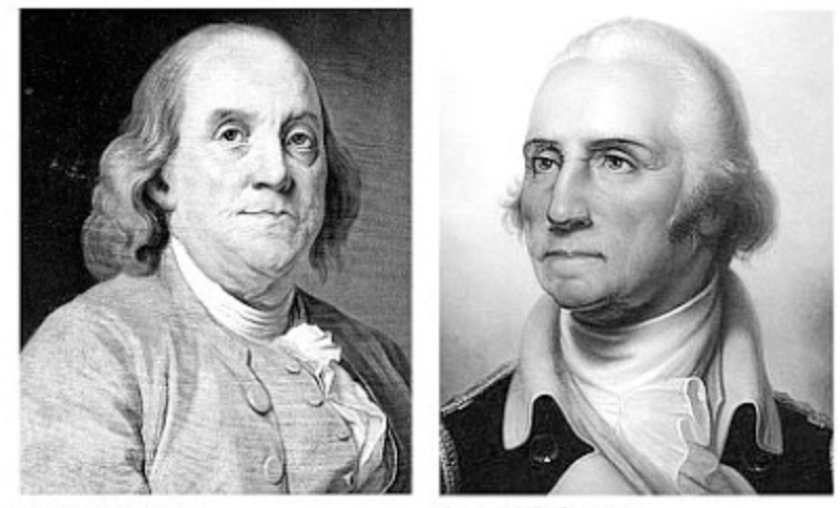

Governing: Rather than the standard portrayal of Franklin as a genial raconteur, you present him in a sterner and more argumentative light.

H. W. Brands: The motivating question for this book was what causes somebody like Franklin to forsake his country and take up arms against it. This was serious stuff. When Franklin is dealing with the British, he’s not charming. He’s all business.

(New England Historical Society)

Getting Inside Big History Through Little History

Governing: With so much to draw from, how did you choose what to feature in this book?

H. W. Brands: Historians look for good sources. If the sources aren’t there, you can’t write about it. I try to get inside the heads of historical figures and let my readers inhabit their world. I try to draw a distinction between what I call big history and little history. Big history is the overarching story. It’s the American Revolution. It’s war and peace. Little history is the story of individual lives. For me, the most interesting part is the intersection of these two.

Look at what happened to the loyalists after the war. They had to leave. That’s why we don’t know more about the loyalists. The good thing for them was that they had a place to go. The worst thing that can happen is if you’re involved in a revolution and you don’t have a place to go. That’s when things get really bloody. You see this in the French Revolution, the Russian Revolution, the Chinese Revolution. It didn’t happen in the case of the United States, not because Americans were more genteel than others, but because the loyalists all fled for their lives, and the British gave them a place to go.

(slaveryinnewyork.org)

What Are the Chances?

With anybody making the choice, you have to weigh your chances of success. Where do you stand on the principles? Where does your personal interest lie? What are the chances of success? What happens if your side wins? What happens if your side loses? In the case of Boston King, as with other enslaved peoples, it was more fraught because, even if the British side won, who knew if they would actually follow through on their promise? Slavery was still legal in the British Empire. Boston King joined the British Army, and at the end of the war he found himself in New York City. He heard that the British have agreed to return confiscated property, and he knew that the Americans considered slaves to be property. Fortunately for King, there was wiggle room in the negotiations. The British did give back horses and houses and buildings, but they didn’t give back the slaves. Boston King went off to Canada as a free man.

Governing: There were occasions in your book where patriots remarked that if they didn’t win this war, they’d be mere slaves. Given where we are culturally at the moment, you can’t read this stuff without just cringing.

H. W. Brands: That’s quite true. It was particularly rich when George Washington used this terminology. Nobody’s going to enslave George Washington, for heaven’s sake. He’s always going to be the wealthiest person in Virginia, at the top of the state’s social pyramid. So one has to decide whether this is just an overwrought figure of speech, or is there something serious going on here? The appropriate first assumption is that he means what he says, so what does he mean? In the first place, he recognizes that his liberties are at risk. Washington’s not going to be whipped or sold down the river, but he thinks that rights that he ought to have are going to be taken from him. He’s not going to wind up in the slave quarters on Mount Vernon, but the imagery is there.

[P]eople looked upon rights in quite a different way than we look upon rights today.

The good news is that we survived. ... The bad news is it took a civil war.

H. W. Brands: It has been divisive from the beginning. We have to compromise to keep this experiment going. When people would ask about the message of the book, I put it this way: “I have been to the 19th century. I have been to the past. I’ve been to a time when the country was even more divided than it is today, and I’ve returned with good news and bad news. The good news is that we survived. We’re still here. The bad news is it took a civil war.” I’m not saying that we’re on the verge of a civil war. But I will say that when any country reaches the point where the people who are on the other side of political issues come to be seen not as folks with a different opinion but as enemies, and when those differences become irreconcilable, then you’re playing with fire. One of the essential components of the emergence of the American independence movement was this judgment on the part of people like Franklin that they were no longer Englishmen. The British weren’t allowing them to be full Englishmen, and so they had to be Americans.

(Flickr/Mark Goldsher)

You can also hear more of Clay Jenkinson’s views on American history and the humanities on his long-running nationally syndicated public radio program and podcast, The Thomas Jefferson Hour. He is also a frequent contributor to the Governing podcast, The Future in Context. Clay’s most recent book, The Language of Cottonwoods: Essays on the Future of North Dakota, is available through Amazon, Barnes and Noble and your local independent book seller. Clay welcomes your comments and critiques of his essays and interviews. You can reach him directly by writing cjenkinson@governing.com or tweeting @ClayJenkinson.