The firebrand Georgia Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene recently tweeted, “We need a national divorce. We need to separate by red states and blue states and shrink the federal government. Everyone I talk to says this. From the sick and disgusting woke culture issues shoved down our throats to the Democrat’s traitorous America Last policies, we are done.”

We need a national divorce.

— Marjorie Taylor Greene 🇺🇸 (@mtgreenee) February 20, 2023

We need to separate by red states and blue states and shrink the federal government.

Everyone I talk to says this.

From the sick and disgusting woke culture issues shoved down our throats to the Democrat’s traitorous America Last policies, we are… https://t.co/Azn8YF1UUy

Although her tweet storm has been decried by a range of more responsible Republicans, mocked and derided by political columnists and late-night talk show hosts, many believe Ms. Greene — who brands herself as “MTG” — is reading the national mood pretty well. On any given day, it does appear that there are at minimum two Americas now, one blue and one red, and that their differences have become irreconcilable.

Irreconcilable Differences?

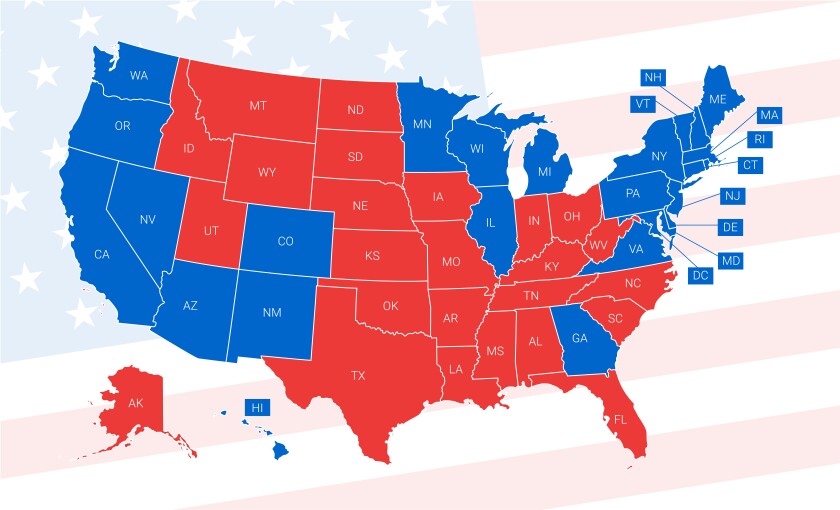

Blue Americans are concentrated on the coasts, in some midwestern states in the Great Lakes region, and in Colorado and New Mexico. Red Americans live in the old Confederacy, up and down the Great Plains, and in the northern Rockies. Much of the “heartland” belongs to the reds, even in states, like Massachusetts, New York and Oregon, where the majority votes blue.

(Shutterstock)

The two essential camps no longer just disagree. As Rep. Greene’s tweet indicates, they despise each other. Liberal attitudes are “sick and disgusting,” she says. Blue Americans are “traitorous,” and they shove their liberal agenda “down our throats.” Blues tend to see the reds as backward, often enough as rubes, racists and rednecks. The reds see the blues as politically correct America-haters and snowflakes, and sometimes as outright communists. In fact, both camps now often declare that they don’t any longer recognize the other side as having political, economic or social legitimacy.

We’ve Been Here Before

It may be useful to take Rep. Greene’s idea seriously for a moment, and to explore the history of secessionist movements in the United States. Her proposal is not without precedent in American history. There have been two giant secession inflection points: the American Revolution (1774-1815) and the Civil War (1861-1865).

Takeaway: Secession frequently but not always is attended by violence and sometimes outright war. Think of the partition of India in 1947 or the catastrophic breakup of Yugoslavia (1991-1992).

The Civil War ended in Union victory (April 9, 1865), but it did not produce national unity of purpose. More than 600,000 died in that war. Slavery as a formal legal institution ended with the Thirteenth Amendment (Dec. 6, 1865), but Reconstruction failed and the Confederate states soon found other means to prevent African Americans from achieving equality of circumstance, equality at the ballot box, social equality, or equality under the law.

You cannot read Heather Cox Richardson’s How the South Won the Civil War (2020) without wondering whether President Lincoln’s determination to hold the union together with force was the right decision. If we had let the Confederate states secede and chart their own destiny, their economy would presumably have collapsed in a relatively brief amount of time. The “price” for re-entering the union would have been to end slavery. If the southern states were unwilling to pay that price, then they’d have to try to muddle on without the benefit of the North’s wealth and emerging industrial gigantism.

It is true that we all have a mystic attachment to one America “sea to shining sea,” and the symbolic tidiness of 50 states (one reason why getting to 51 is so controversial). The idea of breaking up the country seems so grave, so full of disillusionment, so great a loss to the founding idea of America, that most of us regard it as unthinkable. Most, not all.

Jefferson, As Usual

If it should become the great interest of those nations [the western territories] to separate from this … why should the Atlantic states dread it? But especially why should we … take side in such a question? The future inhabitants of the Atlantic & Mispi [sic] states will be our sons … . We think we see their happiness in their union [with us], & we wish it. Events may prove it otherwise; and if they see their interest in separation, why should we take side with our Atlantic rather than our Mispi descendants? God bless them both, & keep them in union if it be for their good, but separate them if it be better.

Jefferson said that as long as our western cousins maintained republican forms of government, and guaranteed the protections enshrined in the Bill of Rights, there was no compelling reason to insist that they all adhere to a single union with a single national capital. After all, commitment to “the consent of the governed” was the foundation principle of the United States.

Translation? Chillax, it’s all going to be fine because American habits and American ideals are always going to characterize our continental experience. We share more than we disagree about.

More recently, for many decades some people in northern California, western Oregon, western Washington and British Columbia have fantasized about secession and the creation of a liberal “green” republic sometimes called Ecotopia, which was the title of a fascinating 1975 utopian novel by Ernest Callenbach. In the last few months and years, conservatives in eastern Oregon, deeply frustrated by the political stranglehold of the liberal population centers closer to the Pacific coast, including Portland, Eugene and Corvallis, have advocated redrawing the Oregon-Idaho boundary so that eastern Oregonians can join Idaho in a new entity called Greater Idaho.

So far 11 eastern Oregon counties have voted to explore the possibility. This would transfer the allegiance of approximately 400,000 people from Oregon to Greater Idaho. Secession advocate Matt McCall says, “We could move that border and get the people in Eastern Oregon governance that they actually want and that matches their values. It makes far more sense for them to get government from Idaho because they’re socially, culturally, economically, politically, much more aligned with Idahoans than they are with Western Oregonians.”

During the Obama administration, Texas and about a dozen other states talked tough about seceding, including in legislative debate (they said it was his “policies”), but they never did.

Things have become so polarized and mutual mistrust is now so great that, according to a 2020 Hofstra University poll, “nearly 40 percent of likely voters would support state secession if their candidate loses.” In a July 2021 University of Virginia poll, 41 percent of Biden supporters and 52 percent of Trump supporters expressed support for the idea “that it’s time to split the country, favoring blue/red states seceding from the union.”

How About Soft Secession?

For starters, he invoked the idea of a Texit (semi-secession) at the red end of the political spectrum and a Calexit at the blue end. This, he said, might relieve some of the dangerous intensity of America’s political abscess. Same-sex bathrooms in Texit, unisex in Calexit. This separation would preserve the union (and America’s essential power in a troubled world) and leave open the possibility of reconciliation somewhere down the road.

Maybe we can endure a certain degree of devolution, just as the British are learning that the 2016 Brexit decision does not utterly cut them off from the trade and security protocols of the European Union.

Imagining the Consequences

I’ve been trying to imagine the consequences. We could agree on a national currency (or not), a national defense establishment, most favored nation trading status in both directions, open borders, and guaranteed freedom to migrate from the wrong American republic to the right one. People would vote with their feet. Within a generation or two most of the blues could live together in one republic and all the reds in another. Red state Americans could sneer about their neighbor, the “People’s Republic of Wokeness,” and blue state Americans could call their former brethren “NASCAR Nation.”

Red America could outlaw or severely limit abortion but allow open season on the proliferation of guns. Red America could define “gender” as either a biologically born man or a biologically born woman (period, end of story), while Blue America could embrace a nuanced multiform view of gender possibilities. Red America could adopt Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the USA” as its national anthem, and Blue America could select John Lennon’s “Imagine.” Blue America could provide cradle to grave national health care and taxpayer-supported college tuition. Red America could privatize Social Security and urge people to play the lottery. Red state taxes would be low. Blue America could legalize marijuana and mushrooms. Red America could cling to good old beer and grain alcohol. Red America could censor and ban undesirable books. Blue America would have to learn to live with freedom of expression in its wildest forms.

Why not? Truly, why not? We should at least think about it.