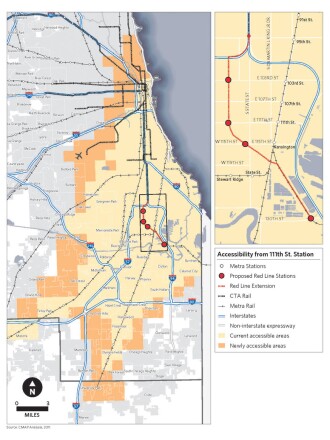

The project, known as the Red Line Extension (RLE), has been in active planning by the Chicago Transit Authority since at least 2006. It would add four new stations and 5.6 miles of elevated and ground-level track to one of the busiest routes on Chicago’s “L” system. It’s an expansion of urban railway infrastructure on a rare scale in an age of funding crises and shrinking ridership for public transit agencies. But local leaders say it’s a long-overdue investment that could cut travel time from the far South Side to the Loop by as much as 30 minutes while providing a host of economic benefits to underserved communities during and after construction.

The CTA completed the environmental review process for the project earlier this month, and is hoping to move into the engineering phase by next year. It’s seeking more than $2 billion in federal funds, with the city and CTA required to put up about $1.6 billion of their own. To raise the local funds, the authority is proposing a new twist on an old tool called tax increment financing (TIF), which has been used extensively to fund economic development in Chicago. And despite some concerns about the proposal raised by several of the city’s aldermen this summer, the project’s planners say they’re confident the Red Line Extension will move forward.

“From our perspective,” says Leah Mooney, director of strategic planning and policy for the CTA, “the opportunity for this project to become a reality has never been better.”

Decades of Waiting, Years of Planning

Mooney officially began working on the Red Line Extension in 2015, but notes that CTA began studying potential routes and transit types for the project in 2006. Two years prior to that, residents of some of the South Side neighborhoods where the extension is now planned expressed their support for the project through a nonbinding referendum. But the lack of a train to the southern edge of the city has been felt for many decades, and former Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley reportedly promised to extend the line as far back as 1969.

“That was a promise made but not kept,” Mooney says. “The reason to do this project is to make good on that promise and also to create new opportunities in this area.”

CTA has now spent over a decade and a half working on the extension, including identifying properties that it plans to acquire through eminent domain to establish the new line. Officials say the investment of time and money are more than justified by the degree of benefit the new line will create. For residents of the South Side, the project is “going to change their lives in ways they can’t even imagine” said CTA President Dorval Carter Jr., in a promotional video.

Connecting Disinvested Neighborhoods

Neighborhoods on Chicago’s South Side have some of the lowest median incomes in the city, as well as low rates of vehicle ownership and usage compared to other neighborhoods. Michael LaFargue, a South Side resident and former president of the Red Line Extension Coalition, which has advocated for the project for years, says extending the transit system to the southern edge of the city is a matter of fairness.

“We’re talking about transit equity, transit justice and environmental justice, because this will reduce some of the pollution in these areas,” LaFargue says.

The Red Line Extension Coalition grew out of the Developing Communities Project, the nonprofit community organizing group led in the 1980s by former President Barack Obama. LaFargue, who works as a realtor and lives in the Roseland neighborhood near the current 95th Street terminus of the Red Line, says that other areas of Chicago have seen major investments, including in transit improvements, while the far South Side has remained cut off from transit access.

“Let us at least get to a job,” LaFargue says. “Why should we be last?"

The CTA expects 38,000 rides a day on the extended portion of the Red Line after it’s completed, representing better access to jobs, education and the full scope of opportunity in the nation’s third-biggest city for long-isolated communities.

Advocates and project planners also point out that the extension would benefit the transit network and therefore the whole city, not just the South Side. Gerasimenko cited a report from the Metropolitan Planning Council which suggested that racial segregation costs Chicago billions of dollars in foregone income every year while contributing to high homicide rates and low rates of educational attainment. CTA is also intending to use the project to invest in workforce development in the far South Side, Mooney says. Chicago also has a robust program of transit-oriented development, which, coupled with new rules that promote affordable housing near transit nodes, planners hope will bring equitable development to South Side communities.

LaFargue says many people on the South Side remain skeptical that the extension will be completed any time soon. Recent milestones that CTA has reached, including finishing the environmental impact study and proposing a funding mechanism, make him more confident that it will finally happen.

“At this point with those types of discussions I am more comfortable, but there are no promises until the city and the state of Illinois actually produces its side of the financing,” LaFargue says.

Redistributing Local Tax Growth

To raise about $950 million of the local share of the project, CTA is planning to create a tax increment financing district that will generate funds for the RLE for the next several decades. Most TIF districts work by freezing the amount of money the city and school district collect in property taxes in a certain area, and redirecting the growth in taxes over time to local development projects.

TIF is used by local officials across the U.S., but nowhere more than in Chicago. The tool was authorized by the state in the 1970s and Chicago created its first TIF district in the 1980s. The use of TIF exploded in the 1990s under Mayor Richard M. Daley, who reportedly called it "the only game in town" for promoting development projects. Popular with officials because it allows them to reallocate future tax-revenue growth rather than spending from the current budget, the program has also been widely criticized for slowly starving public schools of funding, generating benefits unevenly in an already racially segregated city, and generally being an unaccountable "slush fund" for city leaders.

According to a report from the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Chicago has more TIF districts than the rest of the top-ten biggest cities combined, and in 2021 alone it sent more than $1 billion in property taxes to those districts instead of the public coffers. Around a third of all the city’s land sits in a TIF district.

The TIF district that’s planned to fund the Red Line Extension is different from the typical Chicago use of the tool. For one thing, the school district would still collect its full share of the property tax in the district. It’s also unique in that it would generate the tax increment in an area with more economic activity closer to the urban core and distribute its benefits to a public project in the South Side. CTA has referred to it as an “equity TIF,” though Mooney says that’s not an official designation.

“That is a description we’re using to explain what the TIF is actually doing,” she says. “We’re able to leverage some of the growth that’s happened to the downtown to invest in the far South Side, and spread that growth and benefit across the city.”

The TIF plan strikes LaFargue as a good idea.

“My thought is, the South Side has been treated very unfairly for many years, the Black and brown communities here. So if another community has to help pay for those disadvantages, so be it,” he says.

But several of the city’s 50 aldermen raised concerns about the use of the transit TIF for the Red Line Extension at a recent public meeting, according to local reports. One of them was Ward 3 Alderman Pat Dowell, who represents areas north of the planned extension that would generate tax increment for the project. Dowell tells Governing she supports the project.

“There’s no doubt that this extension for the Red Line is long overdue and that it will have tremendous impact in connecting communities that have been marginalized,” she says.

But she says she wants some of the benefits of the TIF district to return to the areas that are generating the increment, which have transit access needs of their own. Another alderman, Anthony Beale, questioned using TIF funds from another area to fund the project as well, even though the benefits would flow to his ward, according to local reports. (Beale was not available for an interview.)

“Equity is an overused word these days,” Dowell says. “I understand the concept and I’m not bucking the concept. I just want my constituents to benefit as well — that’s equity to me.”

Looking Ahead

Dowell says the discussions around the proposal are a “work in progress.” The CTA is hoping for a vote on the TIF by the end of the year. Mooney pointed out that similar concerns were raised over the city’s first Transit TIF, which is used to fund improvements to the Red and Purple lines, but that the City Council ultimately voted unanimously to approve the district. If the City Council follows suit in this instance, CTA is hoping to begin soliciting proposals for a design/build contract next year, with construction anticipated to begin in 2025.

If it’s successful, Mooney argues, both the funding tool and the extension itself will serve the same goal.

“What you’re really looking at here is an opportunity to help take some of the growth that’s happened in the central area and extend it to parts of the city that haven’t seen that kind of growth,” she says.

Note: This article has been updated to correct the local portion of funding and the amount that the TIF is meant to raise.

Related Articles