In Brief:

Another major recession could wipe out West Virginia's unemployment trust fund. That was the warning Scott Adkins, the state's acting labor commissioner, had for senators during debate on a bill to change the maximum number of weeks West Virginians can be eligible for unemployment. “We’re trying to be proactive because we’re going in the wrong direction on that trust fund balance,” he said.

West Virginia isn't the only state worried about its unemployment trust fund balance. The national unemployment rate is 3.9 percent, which means this should be a period when states are able to build up reserves in their unemployment accounts since relatively few people are drawing benefits. As of January, only 19 states and territories met the federal Department of Labor's recommended minimum solvency standard for their unemployment trust funds. By contrast, back in January 2020 at the dawn of the pandemic, 31 states and territories met the minimum standard.

Some states are in more trouble than others. New York started the year with a trust fund balance below $4 million, while it owed the federal government — which replenishes unemployment accounts when they run dry, but under the expectation that states will make them whole — $7 billion. California is in arrears by just under $20 billion.

A state such as Georgia might look like it's in good shape, with a balance of $1.6 billion, but that's enough only to last five months, meaning the state is putting aside less in good economic times than the federal Labor Department recommends. Worried about the situation, legislators proposed allowing the state Labor Department to go after millions of dollars in unpaid unemployment taxes, but the bill stalled.

In addition to limiting weeks of eligibility for benefits, the West Virginia Legislature has passed a bill that would lower the maximum benefit to roughly 55 percent of the state's average weekly wage. Adkins insists the changes are necessary to make the trust fund sustainable.

Some analysts say states are being too stingy. “I think they were being a little conservative," says Sean O’Leary, a senior policy analyst with the West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy, a progressive think tank. "The trust fund is going down, but it always goes down this time of year," before companies pay quarterly taxes.

Still in Recovery Mode

The trust funds, like any savings account, provide a cushion. States try to build up the funds during good times so they have something to draw on when times get rough. Heading into the pandemic, states were able to draw on reserves that had gradually been built up over the decade or so that followed the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009.

Their accounts remain in recovery mode despite the growth that's lasted since the initial economic shock from the pandemic, despite low unemployment rates across the country. In 2021, a year into the pandemic, only 13 states and territories met or surpassed the recommended minimum solvency standard. In 2022 and 2023, that number inched up to 16, before climbing to 19 last year.

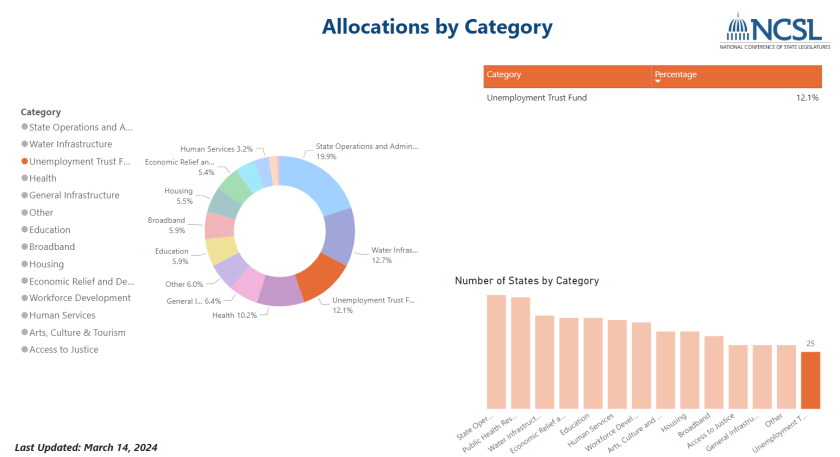

States have sought to find ways of rebuilding their trust funds. Fully half the states had allocated 12.1 percent of the funds from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) to their unemployment trust funds as of December. That represents a total of $24 billion.

“The primary reason these trust funds are heading in the right direction is that a lot of states used stimulus funds to essentially rebuild those trust fund balances,” says Brian Sikma, a senior fellow with the Foundation for Government Accountability, a conservative think tank.

However, some states remain in the red. In California, there's now an imbalance in part because increasing wages has translated into higher average weekly benefits, even as the state continues to tax employers only on the first $7,000 earned by covered workers.

Concerns About a Downturn

Provided unemployment stays low, most states will be able to weather short-term economic downturns, given their current balances. It's concerns about what comes next — what happens during the inevitable next recession, whenever it arrives — that makes some policymakers nervous.

One option that Sikma and other researchers recommend is indexing — providing shorter benefit periods when unemployment is low and longer periods when unemployment is high. Indexing is already used in some form by 11 states. Indexing amplifies the effects of trust funds in general, offering states a bigger cushion with which to ride out bad economic conditions.

Indexing has its critics. While it can be helpful for states, it can present problems for people who lose their jobs when unemployment is low. While overall unemployment may be low, some communities within a state, whether it's racial or ethnic minority populations, residents of areas impacted by disaster, or people who work in layoff-prone sectors such as tech or journalism — may be unemployed for lengthy periods of time but have their benefits cut off due to indexing.

“Indexing certainly has a disproportionate impact on workers of color in our state, because Black workers in Georgia have an unemployment rate above 4.5 percent,” which is well above the statewide average, says Ray Khalfani, a policy analyst at the progressive Georgia Budget and Policy Institute.

One other approach states can take is updating their overall systems. Streamlining processes can be helpful to applicants while potentially opening up resources for flagging fraud, which cost states upward of $100 billion during the pandemic.

A period of relative calm, like the present, offers policymakers a moment in which to be thinking about improvements, whether it's refreshing trust funds or making administrative changes. “Now is a great time for state policymakers to look at tailoring these tools to make sure they’re set up for the next crisis," says Sikma, the Foundation for Government Accountability fellow.