Chart courtesy of Public Funds Investment Institute

One theory might be that federal American Rescue Plan Act and infrastructure funding has landed in state and local coffers and is expected to sit there doing nothing until it’s spent. Possibly there could have been staff apprehension about the audit trail for these moneys, so they reverted to “cigar box accounting” by parking their federal funds in dormant separate accounts.

Yet there appears to be nothing in federal regulations that precludes routine professional cash management practices to generate investment earnings that benefit taxpayers. In fact, there appears to be explicit federal authority to make customary and conventional public cash management investments.

There’s also a timing problem with this theory: Most of this federal funding was not approved by Congress until 2021, and these idle cash balances had already doubled by then. (The CARES Act was passed in 2020, but did not provide funding directly to states and municipalities that year of the magnitude shown in the PFII chart.)

A second explanation — or excuse — might be that as the COVID-19 pandemic hit, banks suddenly started giving out higher earnings credits for public agencies’ “compensating balances.” In theory that’s possible, and not unknown in the banking business, but nobody can cite a rationale for why banks would do that nationwide without a political gun to their heads.

Nor has anybody identified a bank that awards a market-equivalent 5 percent earnings credit on compensating cash balances. Doing so would impair their net interest margins, which are a key measure of profitability watched closely by investment analysts. If this were the case, by now one would expect the professional literature or social media to be loaded with case histories and cost-benefit analyses.

A third and certainly plausible explanation is just “alternative uses of staff time.” When interest rates were below 1 percent a few years ago, the value of cash balances was easy to overlook. Maybe there were better tasks for treasury staffers working remotely during the pandemic than chasing down nickels in the bank accounts.

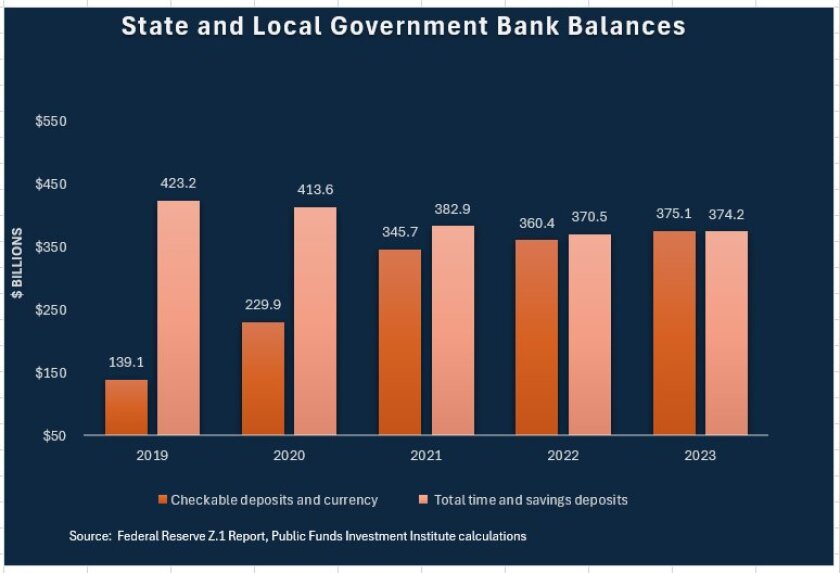

But in today’s market, the marginal income foregone at 5 percent on $375 billion likely exceeds $10 billion nationwide, even allowing for compensating balance credits and “transactional float” (when money is briefly counted twice due to transaction processing delays). Even by congressional standards for wasteful government, that’s a big number for public resources that could be better invested to benefit taxpayers rather than bank shareholders and executives who are the ultimate beneficiaries of lazy-money financial practices.

Then there is the possibility that it’s all a statistical fluke or just a passing wave in a flat ocean: We cannot rule out the chance that next year’s reported 2024 statistics will reveal a sudden plunge in these dormant bank balances, perhaps as the result of disbursements finally completed from all that federal money — or a belated staff awakening that there’s substantial income worth grabbing. As economists like to say about central bank monetary policies, there could be a “long and variable lag” at work here. However, that mantra would describe but still not explain what has been happening since 2019.

So something curious is at work here and it’s yet to be explained conclusively by the professionals who monitor the public treasury marketplace. Certainly it’s a topic worthy of some thoughtful analysis by the major national professional associations whose members are stewards of this cash. Maybe a few on-the-ball academic researchers looking for actionable subject matter can help solve this riddle and promote better cash management practices.

Governing's opinion columns reflect the views of their authors and not necessarily those of Governing's editors or management. Nothing herein should be construed as investment advice.