Well, probably not significantly, for two reasons. One reason comes from better understanding what actually causes inflation; the other is a simple logical analysis of the facts.

There are three basic causes of inflation, which is an increase in the general price level, not just the price of a single good or service. Inflation can result from an increase in the money supply without economic growth, which is “monetary” inflation. Or it can come from total demand for goods and services exceeding supply, which is either “cost-push” or “demand-pull” inflation: too much money chasing too few goods or too few goods to meet demand without prices increasing.

Taking them one at a time: (1) States do not print currency or control the money supply. (2) All that supply chain talk you hear is about the cost-push dimension of today’s inflation, and that has almost nothing to do with these state payouts. The government services that states provide to their economies are usually priced at zero except for user fees, which are incidental and immaterial in the big picture. There is no inflation when the price is zero. (3) So it’s only the demand-pull kind of inflation that state disbursements could ever possibly impact. Otherwise this issue is just political and ideological posturing.

Dollars In, Dollars Out

As to the facts, all of the states except for one (Vermont) operate under some kind of balanced-budget requirement. They can’t and don’t borrow money to fund handouts. Every dollar going out for spending must have a dollar coming in from revenues. The states are typically incapable of increasing what’s called aggregate demand, the sum of all money spent in the economy by consumers, governments and businesses. In short, states simply shuffle money around; they don’t create it.

Then there is the matter of timing. Some of these payment programs were initiated during the pandemic period as economic lifelines to their citizenry, similar to the first round of federal checks back during the Trump presidency. Those payments were clearly counter-cyclical stimulus payments that largely offset household income losses when the economy had shrunk, as businesses were shuttered by lockdowns and people were staying home rather than spending locally or traveling. Although some of that pandemic-relief cash was saved until this year and not spent before inflation kicked up, most of it was long gone by last Thanksgiving and had almost nothing to do with the alarming price increases we’ve seen in the past 12 months.

Next, there are the distributions of cash that went from state treasuries to taxpayers because their laws put a cap on tax revenues and require a rebate. Those dollars are almost by definition non-inflationary, because it’s simply squaring out the books in the national income accounts. Again, it’s money that the states themselves have shuffled, not spent. Although some can rightfully argue that these rebates were essentially a reduction in tax collections (which is stimulative, hence injecting aggregate demand), they were not a tax cut but a tax cap. That’s a distinction with a difference. Those states have all collected — and kept — more dollars in taxes than they had the year before. Ultimately, their tax-cap rebate money simply moved the leftovers from taxpayers’ left pockets to their right pockets. So it’s hard to get too excited about tax-cap distributions being inflationary.

A close cousin of the tax rebates and tax caps is the handful of states that cut their gas taxes to provide their residents with financial relief at the pump. Think about it: Cutting the cash-register cost of a product at the consumer level is hardly inflationary. Gas-tax holidays are arguably a short-sighted transportation funding policy, but they are clearly not causing inflation.

Robin Hood Income Transfer

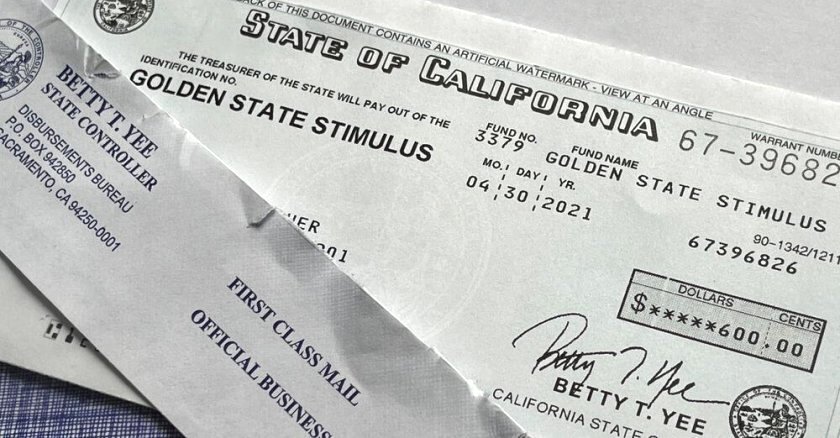

That brings us to the last category: economic- and inflation-relief payments. Let’s just call them “stagflation relief.” Today, California is the biggest of these, with a new program underway to offset household inflation. Although it’s officially labeled a middle-class tax refund, its proponents have gone out of their way to tout it as blue-state relief to household budgets to counter rising prices in the face of slowed economic growth. The payments are scaled inversely to household income — with descending payments at higher incomes that shrivel to zero at the highest end — so it’s hardly a “rebate.” In reality, it’s a progressives’ Robin Hood income-transfer scheme on both the tax and spending sides.

Meanwhile, California is already seeing a fall-off in income-tax revenues because of stock market losses that have shriveled its typically huge revenue source of capital-gains taxes, so I’d say it’s a dubious fiscal policy to be refunding taxes from an eroding base when the state’s rainy-day fund may soon need infusions for the next fiscal year. But this was election season, after all. And we all remember the grandstanding Trump stimulus check signatures in 2020, so both political parties play this game.

At the end of the day, the California payments are clearly a macroeconomic injection of cash at a time when the economy is running at full employment, which undoubtedly adds fuel to the inflation fire locally, at least in theory. However, the real-world problem for inflation-hawk critics and political spin doctors is that it’s really only a single drop of diesel on a forest fire: The total of these one-time payments is about $10 billion in a $3 trillion statewide economy. By the time that money gets to the grocery stores, it’s a rounding error in the Golden State’s total consumption. Even if every dollar of this largesse went to price increases and not the base costs of goods and services, it would contribute one-third of 1 percent to inflation in California, and just 0.03 percent to the national consumer price index.

When you add up all of the new state-level stimulus programs getting underway across the country, totaling about $31 billion, you get a national inflation impact of just a fraction of one-tenth of 1 percent. Bottom line: The inflation-kvetching about these states’ fiscal palliatives for households is overblown.

Governing's opinion columns reflect the views of their authors and not necessarily those of Governing's editors or management.

Related Content