But what about times like today, when most states are experiencing budget surpluses and strong revenue growth? Our advice: Don’t let up on the evidence “accelerator pedal.”

Even in times of plenty, getting the most return on investment from agency spending is crucial. Using evidence to inform the budget builds trust with taxpayers that their dollars are being used wisely, no matter the fiscal conditions. And while revenues may be robust, so are states’ challenges, from expanding economic mobility to increasing health and wellness to many other urgent issues. It’s why we need programs that work and that use evidence to continually improve their results.

So how can states that are new to evidence-based budgeting get started? We have a few suggestions, which could be implemented individually or together:

Require evidence for budget increases: A relatively easy first step is to require agencies that propose an increase in a program’s budget (say, 5 percent or more) or that propose a new program to provide evidence of effectiveness, even if preliminary. That could include requiring a simple program logic model, a set of performance metrics and an evidence rating, meaning a determination of how strong or weak the research demonstrating the effectiveness of the program model is. To keep the last piece simple, agencies could be required to submit a program evidence rating only if the program is already in the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Results First Clearinghouse Database. The database has evidence ratings for more than 3,150 programs.

Those pieces of data and evidence, then, can be used by decision-makers, such as a governor’s office or a legislative budget committee. They can also help start a tradition of requiring evidence for proposed budget increases that can be useful in the future, including when budgets are tight and evidence can inform tough tradeoffs.

Develop program inventories: Another related approach is to choose a few priority policy areas and develop program inventories for each. Those policy areas might be workforce development, criminal justice reform, early education or whatever areas are most important to leadership.

What are program inventories? They’re lists, often created by using a basic spreadsheet program, of all the programs in a given policy area. For each program, the inventory provides information similar to what we described above, such as a logic model, performance measures and an evidence rating. Program inventories help decision-makers answer questions such as: How much evidence is behind the programs we fund in this policy area? Where are there gaps in our services? And where is there overlap or duplication?

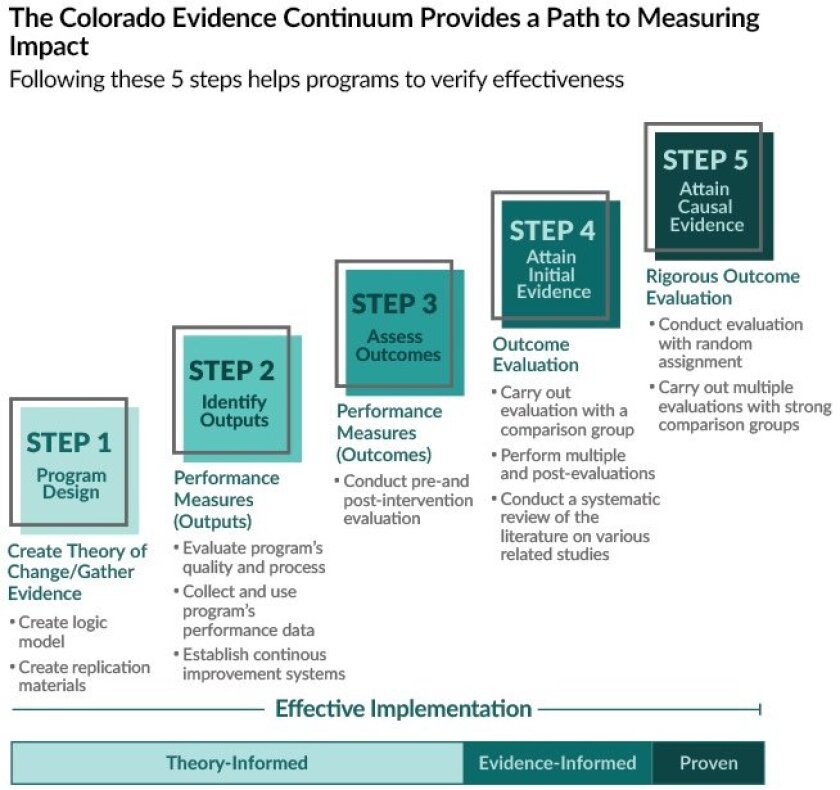

Create an evidence continuum: It’s a visual graphic that describes different evidence levels, from weaker but foundational forms of evidence (such as a logic model) to the most rigorous (such as impact evaluation using random assignment). A good example — and one that other states can use or adapt to their needs — is Colorado’s:

(Source: The Pew Charitable Trusts/Colorado Governor’s Office of Planning and Budgeting)

Put strategies into practice: We’ve seen firsthand how evidence-based budgeting strategies like these can support decision-making and strengthen a culture of accountability for results. That includes the experience of Minnesota, which has inventoried more than 700 state programs and enacted 20 evidence-based proposals totaling $150 million in new investments in the last four years. Tennessee, meanwhile, has created four program inventories in priority areas and will be expanding its inventory efforts to cover an additional 20 state agencies over the next two years. New Mexico is adding program inventories as well, while also monitoring programs’ implementation though its new LegisStat initiative. And Ohio is strengthening the use of the data and credible evidence to inform decision-making in its fiscal year 2024-25 budget with new budget guidance.

These types of evidence-based budgeting strategies are useful today, to help steer resources during times of plenty, and they’ll be useful down the road to inform trade-offs and tough decisions when resources are scarce. They’re efforts rooted in the belief that — no matter what our fiscal conditions — evidence and data should have “a seat at the table” when important policy and budget decisions are made. They’re also helping create a culture in which agencies use evidence and data in managing programs, underscoring the importance of not only smart budgeting but also effective implementation.

Andrew Feldman is the founder and principal consultant at the Center for Results-Focused Leadership, which helps public agencies use evidence, data and strategy to improve their results. Christin Lotz is the director of the Office of Evidence and Impact within Tennessee’s Department of Finance and Administration. Kimberly Murnieks is the director of the Ohio Office of Budget and Management. Charles Sallee is the deputy director of the New Mexico Legislative Finance Committee. Jim Schowalter is the commissioner of Minnesota Management and Budget.

Related Content