In Brief:

"Without data, you're just another person with an opinion." This maxim is attributed to engineer and mathematical physicist W. Edwards Deming, a founder of the information and technology-driven Third Industrial Revolution.

Lack of data, and data delays, opened the door for opinions to dominate during critical periods of the pandemic. Some elected officials issued health orders based on opinions. Some opinions became vested with destructive power to imagined conflicts between personal freedom and life-saving public health practices.

A white paper from the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE), published four months before the country’s first COVID-19 case, called for the development of a robust data infrastructure. The paper was prescient, painting a picture of what was about to unfold.

“The consequences of slow data sharing are significant — delayed detection and response, lost time, lost opportunities, and lost lives,” the authors wrote.

When a public health emergency (PHE) was announced in January 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) gained temporary authority to collect new kinds of data from hospitals. States shared data that they didn’t normally share. That enabled a sort of test case of national data sharing, though with a narrow focus.

As long ago as 2006, the federal Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act ordered the secretary of health and human services to establish a “near-real-time electronic nationwide public health situational awareness through an interoperable network of systems to share data and information.” The mandate was reaffirmed in subsequent legislation but has not been accomplished.

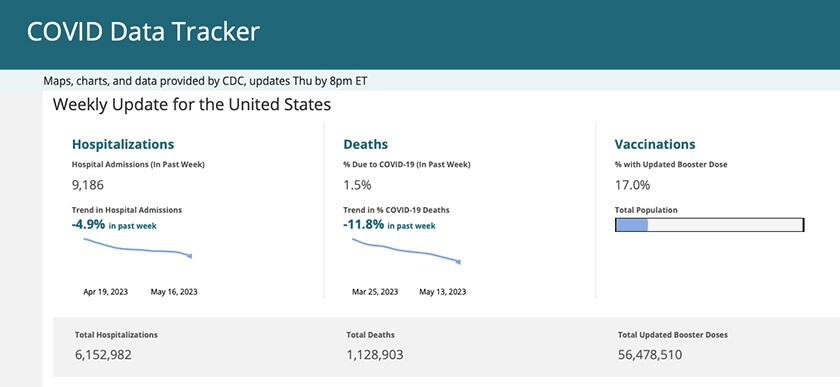

With the end of the PHE, CDC will lose its authorization to collect some types of data. It will still track weekly hospitalizations, the presence of the COVID-19 virus in wastewater and other data points. But the kind of data infrastructure envisioned by the CSTE that could track the future course of COVID-19, or other health crises, won't happen.

(CDC)

Seizing the Moment

The pandemic could have been a watershed moment for public health in the same way that 9/11 was to public safety, says Colin Planalp, senior research fellow at the State Health Access Data Assistance Center (SHADAC). Within a year, Congress created and funded an entirely new cabinet-level agency to prevent future terrorist attacks.

“Here we are more than three years after the pandemic began, with a U.S. death toll of over a million lives,” he says. “Instead of learning from what we built, and learning from our shortcomings, we're starting to dismantle a lot of the hard work that we cobbled together in an emergency.”

Janet Hamilton, an epidemiologist who took over as executive director of CSTE in March 2020, doesn’t want the moment to be lost. “Data modernization, and the work we do within public health to receive, process and act upon data is the most critical issue in front of us.”

Hamilton is concerned that fatigue or perceptions that the pandemic response is “done” could take attention and resources away from building a modern data infrastructure. That is more important than ever, she says.

“If it were a construction project where you could see the remains of the site and the roads not meeting each other, that would give people a different kind of feeling — but the data world doesn’t have that visual reality for people.”

The need for better information systems isn’t limited to COVID-19, or even the next pandemic. Planalp has been studying opioid abuse — a public health crisis shortening lives and costing about a trillion dollars each year — for a decade.

“The data infrastructure for researching and monitoring the problem is woefully inadequate,” he says. “I could tell you how many people drowned in bathtubs versus swimming pools last year, but I can’t tell you with certainty how many people died of fentanyl overdoses.”

Obesity, heart disease and dementia are just some of the other health problems to which the word “crisis” has been applied. One in 4 respondents to a recent Ipsos poll said that gun violence is the country’s No. 1 health threat. (Firearms are the leading cause of death for American children and teens.)

All of these could be better managed with better data.

(Dania Maxwell/TNS)

Removing Legal Barriers

The American public health system operates on a model established in the 19th century. Each state has its own health department, data system and rules about what kind of data can be shared.

Now that the PHE is over, the CDC is in the process of renegotiating data use agreements with states so it can continue to collect some COVID-19 data from them. But the enterprise scale, interoperable data system that Congress and CSTE want to see can’t be created without changes to state laws on sharing health data or uniform data standards.

Even if the CDC had the authority to collect enough data to make national health surveillance possible, states aren’t ready to provide it, says Lilian Colasurdo, director of public health law and data sharing for the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO).

ASTHO is working with states to collaborate around how such a system might work, and how to address conflicting prohibitions about sharing certain kinds of data. In a system patched together state by state, what’s already in law — and what might need to change — varies. Agreement about what will be collected and what the system will look like is essential to moving forward, Colasurdo says, as is guidance from CDC.

The technology exists to get data from health facilities to public health departments to the federal government almost in real time, says Michael Fraser, ASTHO’s CEO. The technology needs to be funded, however, and politics could possibly get in the way of changing data-sharing rules in some states.

“It’s a tricky time to try and change state law around which data get reported to federal agencies,” Fraser says.

It’s a Process

On May 23, hundreds of public health stakeholders met in Chicago for a three-day public health tech expo organized by ASTHO, to confront what comes next. “It doesn’t happen overnight; there’s a process,” says Fraser. “We have to have state public health attorneys there, state epidemiologists, lab people, health officials, CDC.”

At the federal level, an Office of Public Health Data, Surveillance and Technology has been created within the CDC. It will lead work on a CDC Data Modernization Initiative set in motion by a $50 million allocation in the FY 2020 budget. More funding came through the CARES Act and the American Rescue Plan, during a period when CDC data collection was focused on COVID-19.

Congress dedicated $100 million in FY 2022, and $175 million in FY 2023, to improving surveillance and analytics in state and local health departments and the CDC. But the nonprofit Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society believes it would take an investment of $36.7 billion over the next 10 years to “digitize, modernize and interoperate” integrated health data infrastructure.

As big as this number looks, it pales in comparison to the cost of inadequate detection and surveillance. It’s been estimated that the economic impact of the pandemic on the U.S. was $16 trillion. Long COVID-19 could add almost $4 trillion. Chronic diseases that are largely preventable through public health interventions are the leading drivers of more than $4 trillion in health-care costs each year.

Data gaps bring risk right now, says Planalp. “We could get a new variant that pops up tomorrow, and we could be flatfooted tomorrow if it takes time to ramp back up our data collection and data reporting efforts.”

Related Articles