In Brief:

The COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE) declared in early 2020 officially ends today, May 11, 2023. This means that emergency support and funding for pandemic response from the federal government will wind down (expanded Medicaid benefits ended in March.)

It doesn’t mean that it’s time for the country to close the book on the most destructive pandemic in its history. World Health Organization (WHO) Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus made that point on May 5 when he announced the end of the global COVID-19 emergency.

“If we all go back to how things were before COVID-19, we will have failed to learn our lessons, and we will have failed future generations," he warned.

As of April 13, more than 1.1 million Americans have died from COVID-19. Its economic impact has been estimated to be $16 trillion.

Researchers are just beginning to understand “long COVID” (persisting symptoms after recovery from a COVID-19 infection), but based on what is already known, Harvard economist David Cutler estimates that the cost of lost earnings, increased medical spending and decreased quality of life is $3.9 trillion. At present, as many as 4 million Americans are unable to work because of long COVID.

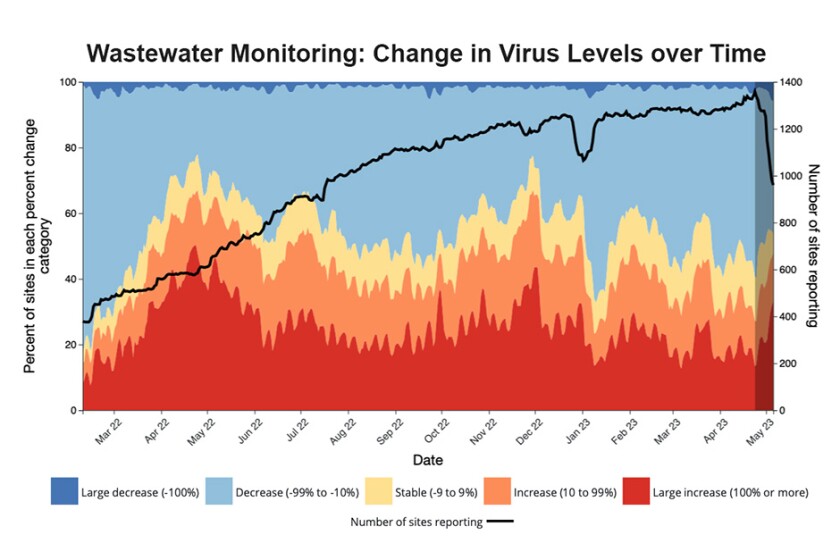

Deaths reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have been in much lower ranges than seen at the height of the pandemic for more than a year (see graph). But a third of the CDC’s surveillance sites are still reporting moderate to high levels of the COVID-19 virus in wastewater and 39 percent of them say the levels are increasing.

How do citizens see things? A Gallup poll in January found that half of Americans believed the pandemic was over, but 1 in 4 were still worried they could catch the virus.

Attitudes regarding the state of the pandemic — and preventive behavior — varied significantly according to party affiliation, however. The country may be coming out of an unprecedented public health disaster with as much to learn as when the virus first emerged.

The Next Unknown

For the time being, vaccines will be free to those with health insurance. At-home tests will no longer be fully covered by Medicare or health insurance. Medication to prevent severe cases, such as Paxlovid, will be free while current supplies last. Absent interventions on their behalf, the uninsured could pay full price for tests, vaccines and treatments in some cases.

Health departments are working to make sure that persons most likely to get severely ill have access to vaccines and medications, says Michael Fraser, the CEO of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officers (ASHTO). “There are plenty of federally purchased vaccines available and we continue to encourage vaccination as the best way to prevent severe illness from COVID.”

One great unknown is the fallout from the unwinding of pandemic Medicaid benefits and the return of enrollment requirements. It’s been estimated that as many as 18 million people could lose coverage, and that 4 million of them will not be able to find other health insurance.

Nearly half of state and local public health workers left their jobs between 2017 and 2021. An additional 80,000 workers are needed, but if current trends continue it’s possible that 80 percent of workers who have been on the job three years or less could leave by 2025.

Emergency dollars that enabled health departments to hire workers will be gone. JP Lieder, founding director of the Center for Public Health Systems at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, is concerned about the potential for those who lose coverage to overwhelm understaffed health departments.

Some states still rely on health departments to provide safety net clinical care, Lieder says. “This is year one of COVID recovery on a normal budget, so the question becomes whether that is up to the task of ongoing COVID management along with all the other things that health departments have to do.”

Can Historical Patterns Be Broken?

Since 9/11, the federal government has picked up most of the tab for public health emergency response. Lieder doesn’t see this as sustainable. There’s no reason to assume that it will be decades or more before the next pandemic; viral threats can come from anywhere in the world, a hard-learned lesson from COVID-19. States need to step up.

“Imagine only funding firefighters when your town is on fire,” he says. “That would be insanity, yet that’s what we do every time there’s a fire in public health.”

Conversations around the consequences of underinvestment in public health have been ongoing for decades, and it’s not certain that even pandemic losses will prompt most states to spend more. It’s hard to convince policymakers to invest in work that brings benefits over the span of years, a policy “win” that can be imperceptible to the public (or a politician).

Discord in Congress might force states to rethink things. “What will you do if you know that Congress can barely agree on a budget?” Lieder asks. “It’s not going to be enough to count on them to fund public health.”

Are states likely to act differently post-PHE? “History tells us that once a public health emergency eases, it's quickly out of the mind of appropriators,” says Lori Tremmel Freeman, CEO of the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO). “I think that we will continue to see the ‘bust and boom’ cycle.”

Two years of work by a bipartisan commission in Indiana resulted in a bill that could boost public health funding, notes Anand Parekh, chief medical adviser for the Bipartisan Policy Center. It now awaits the governor’s signature.

“This is an example of a state taking leadership and saying, 'We're not going to wait for Washington,'” Parekh says.

“On the flip side, we’ve seen rollbacks of public health authority in many states — these are short-sighted, because in the next emergency they are going to be behind, trying to catch up with an infectious disease moving faster than their actions.”

(CDC)

Moving Forward

The fact that 80 percent of the population has received at least one COVID-19 vaccination is a big reason the PHE is ending, says Brent Ewig, chief policy and government relations manager for the Association of Immunization Managers. “The updated numbers are 3.2 million lives and over a trillion dollars saved.”

Anti-vaccination sentiment made headlines, but when vaccines became available, people voted with their feet by landslide margins, Ewig says. Childhood immunization rates remain at 94 percent. This is a 1 percent decrease from pre-pandemic levels, but some polling data shows that trust in routine vaccinations may be up slightly.

In April 2022, Brown University researchers estimated that half of the people who died from COVID-19 after vaccines became available might have been saved if they had been vaccinated. It’s hard to assess how efforts to reach them fell short, Ewig says.

“Was it a failure of our imagination and public health to reach those people that needed us, or was it due to misinformation — and how much did misinformation from our leaders play a part in that? It’s an important question.”

Vaccinations and boosters remain important. Parekh notes that there are still about a thousand people a week dying from COVID-19. It was the fourth leading causing of death in 2022.

It’s not a matter of “moving on,” but of “moving forward,” Ewig says.

(Francois Roux/Shutterstock)

Would We Do Better?

“If a new pandemic were to occur tomorrow, would we do better?” Parekh asks. “I’d be hard pressed to say that — but it’s not a question of if, but when, the next pandemic will occur.”

Lieder notes that past federal investments in biomedical research played a major role in turning things around. Effective vaccines were available within a year because earlier research had developed a platform on which they could be made. Federal support for such efforts remains strong, he says.

“In the predictable cycle of panic and neglect, we're solidly back in the neglect,” says Ewig. “There aren't a lot of serious efforts to learn the lessons from this event and then to put them into policy.”

In 2021, several foundations provided funding to a group of experts to lay the foundation for a COVID-19 commission. Led by former 9/11 Commission Executive Director Philip Zelikow, the COVID Crisis Group undertook this work, but the public sector didn’t respond with a plan to take things further. In 2023, the group published an investigative report, Lessons from the COVID War.

There are other things that Ewig and his association consider to be important at this moment. “First, let's remember and honor the more than a million American lives that have been lost,” he says. “The second thing is to honor all those public health and health-care workers who have been working beyond exhaustion to try to save lives.”

At some point, he’d like to see a national dialog about a memorial that can be a focal point for mourning and healing.

For NACCHO’s Freeman, emergency response isn’t the place to start as the nation leaves the worst days of the pandemic behind. Many Americans use emergency rooms for primary care, she says, and response to societal health emergencies shouldn’t follow that model.

“There's a need to rebuild the system from scratch as far as I'm concerned, so this country is focused much more on prevention and creating opportunities for us to prepare for public health emergencies.”

Related Articles