In Brief:

Did you hear the one about the mayor who discovered billions of dollars, hidden in plain sight, that could be used to fund vital government programs? It’s happened more than once.

Last June, the Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA) announced that six jurisdictions had been selected for an inaugural cohort in an incubator called Putting Assets to Work (PAW). A 10-month process, PAW was designed to help them take a fresh look at publicly owned assets and imagine ways to manage them with strategies used by private-sector developers.

Some cities in Europe and Asia have done this with great success, creating “Urban Wealth Funds” (UWF) managed by private holding companies. These UWFs are tasked with maximizing the value of public assets and operate independent of government influence.

This exact model has not been implemented in the U.S. and may not work here given the complicated fabric of property ownership in American cities. But the possibility of unlocking significant, untapped wealth in publicly owned buildings and land is enough to inspire administrative solutions — or, at least, to try. According to Dag Detter, an investment adviser who served as president of the Swedish government’s holding company, public wealth is twice GDP.

PAW is a collaboration between GFOA, the University of Utah’s Sorenson Impact Center and Urban3, a company that provides economic analysis to local governments using geospatial modeling. It is led by Ben McAdams, a senior fellow at the Sorenson Center who has served as mayor of Salt Lake County and in the U.S. House of Representatives.

McAdams had his own awakening when, as mayor, he had Urban3 do an inventory of government-owned real estate in Salt Lake County. He learned that if the county managed its property in the same way as private owners of property near to it, its value would be at least $45 billion. Even conservative management could bring hundreds of thousands of new dollars to the county, and McAdams was able to make this a reality.

The first cohort of cities has wrapped up its term. “What we’re seeing is that different jurisdictions are pioneering different aspects of this approach to meet whatever the highest needs of their community are,” McAdams says.

Atlanta, part of the inaugural group, is focused on addressing an affordable housing shortage in one of the fastest-growing large cities in the country.

(City of Atlanta)

A Strike Force

Metro Atlanta needs 27,000 more housing units that are affordable to households earning at or below 50 percent of the median income in the area (just under $70,000 according to recent Census estimates). When Mayor Andre Dickens took office in January 2022, he set a goal of building or preserving 20,000 additional affordable housing units by 2030.

From the beginning, a key focus of this work was the creative use of public land to fill this gap, says Joshua Humphries, senior housing policy advisor to the mayor. This included attention to all the needs of the neighborhoods where housing would be located, from grocery stores to child-care centers.

“We pulled together what we called our housing strike force to look across all of the publicly held land and ask what we are collectively trying to accomplish in our neighborhoods,” Humphries says. The resulting collaborative atmosphere proved to be an accelerant; 35 public land projects are currently in the pipeline, either under construction or in the process of selecting development partners.

“Some are still in some level of due diligence, which is very important to this conversation,” says Humphries. One aspect of this is understanding how the land in question was acquired, another looking at how it could be used over the long term to both provide affordable housing and generate revenue for the city.

An aging fire station needing renovation sits on an acre of land in midtown Atlanta. “We called the fire chief and asked, ‘What if we give you a brand new fire station that didn’t cost you anything, but you had to put affordable housing above it to get the new fire station?’” Humphries recalls.

The chief’s answer: “I get a new fire station?!” Thirty stories of housing are planned, with the land leased to a developer, generating long-term revenue for the city.

(City of Atlanta)

Thinking Like a Developer

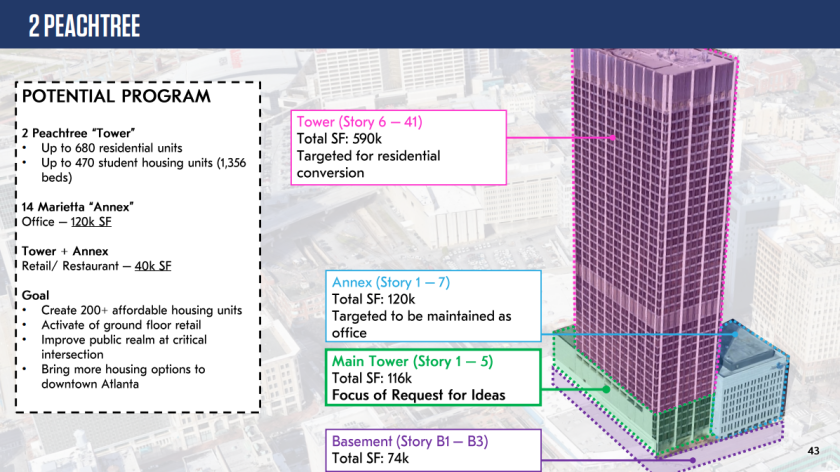

Another large-scale project in downtown Atlanta involves a property acquisition by the city. Two Peachtree Street, a 44-story building, had been used for state government offices for decades. The state decided to move out and put it on the market.

“We got in touch with the governor's office and said there's something special here — we could build mixed-income housing on this site, but we need your help,” said Humphries. The parties negotiated a below-market purchase, and the city is now looking for a development partner to bring an estimated 700 new housing units to the center of the city.

Downtown has long lacked residential housing stock, and Humphries believes these kinds of projects will help downtown thrive as well as helping the housing ecosystem in the entire region. It’s the area with the highest capacity to take on new housing, and has infrastructure in place to support it, something that is not a given everywhere new housing might be developed.

“We’ve got hurting class C office stock and we’re very concerned about what that means for the health of downtown,” Humphries says. The Two Peachtree project could serve as a market leader for taking excess office space offline and turning it into housing. “This type of project ticks a lot of public benefit boxes.”

(City of Atlanta)

A different kind of project is underway in a neighborhood called Thomasville Heights, the lowest-income census tract in the state, home to the lowest-performing school in the state. When the city did its property survey, it discovered 80 acres of publicly owned land in Thomasville Heights, in adjacent parcels that were often vacant and underutilized, contributing to bad conditions in the neighborhood.

The city met with residents to develop a master plan for Thomasville Heights, asking about their goals for the neighborhood and what the best version of it would be. “The plan's being adopted now, and because we own the land and have teams ready to go, we are moving right into the development phase of this work,” Humphries says.

So far 2,300 of the units Mayor Dickens promised have been built, with another 5,400 currently under construction.

(City of Atlanta)

Toward Agile, Resilient Budgeting

One of Atlanta’s biggest innovations, McAdams says, is its focus on scaling development of its assets to make the process more “self-executing” — shortening the runway for getting projects online by having clear guidelines and regulations in place. Others in PAW’s first cohort have taken their experience in different directions.

Anne Arundel County wants to use assets to fund its work in climate adaptation, says Shayne Kavanagh, GFOA’s senior manager of research. Cleveland is focused on economic vitality.

These are examples of the kind of thinking that GFOA has been working to foster through yearslong research and publications highlighting agile, resilient ways for governments to think about budgeting and revenue sources.

Although PAW is selecting participants for a second cohort of five or six jurisdictions, Kavanagh expects it to evolve into more of “rolling model” open to cities on an ongoing basis. “If people like the idea and want to explore it, we want to help them.”

"I spent years as mayor trying to figure out how to do a Scandinavian-style urban wealth fund and concluded that what it's going to take in the U.S. is to start incrementally,” says McAdams. “I don't think there's a wrong approach; it's just going to take people like those in the city of Atlanta, innovating and figuring out what's going to work locally.”