Federal, state, local and tribal leaders across the country are currently responsible for administering a hefty portion of the $1.2 trillion federal infrastructure investment passed in 2021. With this funding comes a once-in-a-generation opportunity to reimagine the future through infrastructure planning decisions. Leaders must seize this opportunity to produce more equitable outcomes, including having those harmed by past decisions at the table and encouraging and considering their opinions equally. Otherwise, these dollars risk doing more harm than good.

There is perhaps no better example of discriminatory infrastructure planning than what happened decades ago in Washington, D.C., where a massive highway project wreaked harms still felt to this day — harms documented in Divided by Design, a new report by Transportation for America, a program of Smart Growth America.

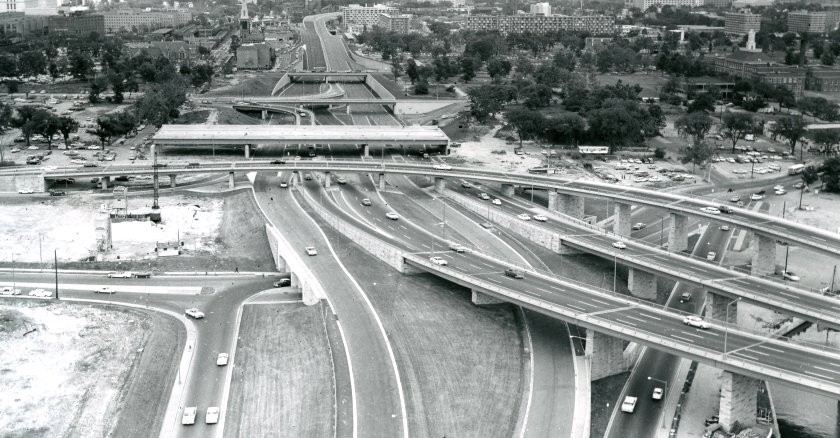

When federal highway dollars were dispersed to cities in the 1950s, construction of the D.C. segments of I-395 and I-695, known locally as the Southeast and Southwest Freeways, resulted in 400 acres being cleared and 23,500 people being removed from their homes. Ninety-nine percent of the buildings in D.C.’s Southwest quadrant were destroyed, including 1,500 businesses. This destruction disproportionately affected Black residents: Of those displaced, 63 percent were Black and 29 percent were white. The destruction that I-395/695 wrought led to $1.4 billion in lost home value; using the 2023 residential property tax rate of 0.54 percent, that works out to $7.6 million in lost property tax revenue per year.

Beyond the staggering number of people who lost homes and businesses, the new freeways also made many neighborhood essentials inaccessible — from health-care providers and grocery stores to child-care centers — and limited proximity to family and friends. The resulting economic and health inequities still exist.

This story isn’t unique to D.C. It’s a pattern that was repeated in cities of every size. While the people who made those highway decisions aren’t making them today, and these communities have been forever changed, today’s leaders can seek to address past harms and rebuild public trust through thoughtful, equitable transportation and land-use decisions.

There are specific steps leaders can take. To start, they must assess what matters most for communities, recognizing, for example, that commuting to work isn’t the only goal of transportation planning. In fact, shorter, non-work trips make up most trips taken.

Second, our primary goal should no longer be only to move motor vehicles quickly. We need to measure how well our transportation system gets people to where they want to go by any means. Black and brown communities most often pay the heaviest price for standards that prioritize the speed of cars over walking, biking and transit.

And finally, we must build trust by listening to and responding to community voices. Bike lanes and sidewalks aren’t enough. Building trust means prioritizing equity with every investment and centering historically impacted communities in infrastructure investment decisions.

As our leaders contemplate the future of highways, public transit, bike lanes and other uses of federal infrastructure funds, they should first reflect on past decisions as a guide for rebuilding trust with communities, use data that looks beyond vehicle travel to help remedy past mistakes, and work to ensure that everyone has access to a place to live that fosters health and opportunity.

Calvin Gladney, a resident of Washington, D.C., is the president and CEO of Smart Growth America. James Hardy, a former deputy mayor for integrated development in Akron, Ohio, is a senior program officer at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which supports Smart Growth America’s Reconnecting Communities project.

Governing’s opinion columns reflect the views of their authors and not necessarily those of Governing’s editors or management.

Related Articles