Signing up for health insurance on the new state and federal exchanges was supposed to be the easy part of the Affordable Care Act. The really dicey part, lots of health policy experts have always feared, would come on Jan.1.

That is when Americans who have enrolled in health insurance for the first time under the ACA begin to discover that having coverage doesn’t guarantee them easy access to a primary care doctor, dentist or mental health professional.

Some changes in the works, such as the use of new technologies and allowing mid-level medical providers to perform some functions usually reserved for doctors and dentists, should improve health care access in the long run. “In the meantime,” said Linda Rosenberg, president of the National Council for Behavioral Health, “people are going to suffer.”

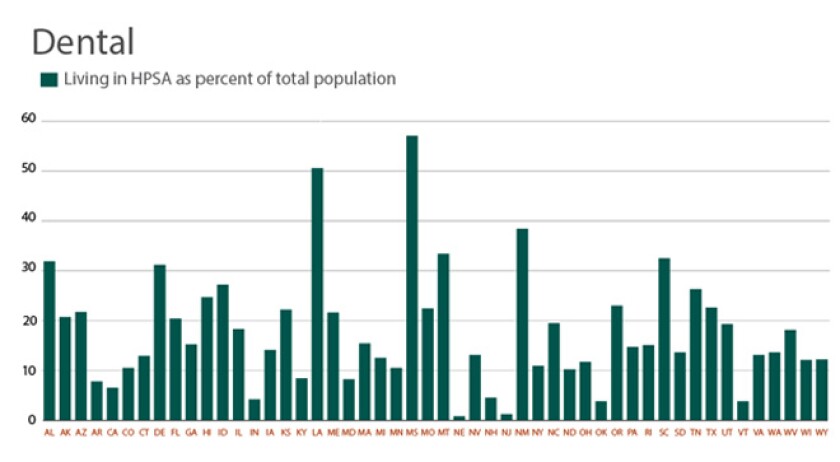

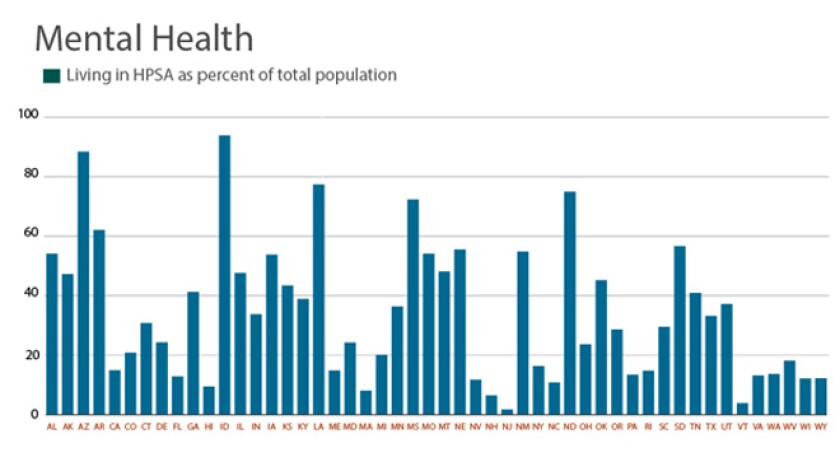

According to the Health Resources and Services Administration , the federal agency charged with improving access to health care, nearly 20 percent of Americans live in areas with an insufficient number of primary care doctors. Sixteen percent live in areas with too few dentists and a whopping 30 percent are in areas that are short of mental health providers. Under federal guidelines, there should be no more than 3,500 people for each primary care provider; no more than 5,000 people for each dental provider; and no more than 30,000 people for each mental health provider.

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), unless something changes rapidly, there will be a shortage of 45,000 primary care doctors in the United States (as well as a shortfall of 46,000 specialists) by 2020.

In some ways, the shortage of providers is worse than the numbers indicate. Many primary care doctors and dentists do not accept Medicaid patients because of low reimbursement rates, and many of the newly insured will be covered through Medicaid. Many psychiatrists refuse to accept insurance at all. Christiane Mitchell, director of federal affairs for the AAMC, predicted that many of the estimated 36 million Americans expected to gain coverage under Obamacare will endure long waits to see medical providers in their communities or have to travel far from home for appointments elsewhere.

During the debate over the ACA, Mitchell said the AAMC pushed for the federal government to fund additional slots for the training of doctors, but that provision was trimmed to keep the ACA from costing more than a trillion dollars over 10 years.

Aging Boomers

There are various reasons for the shortages. Certainly a big contributor is the aging of the baby boomers, who may still love rock ‘n roll but increasingly need hearing aids to enjoy it. The growing medical needs of that large age group are creating a huge burden for the existing health care workforce. The retirement of many doctors in the boomer cohort is compounding the problem.

The federal government estimates the physician supply will increase by 7 percent in the next 10 years. But the number of Americans over 65 will grow by about 36 percent, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Money also is a factor in the shortages. During the course of their careers, primary care physicians earn around $3 million less than their colleagues in specialty fields, which makes primary care a less appealing path for many medical students.

In mental health, the problem is that much of the work is in the public sector, where the pay is far less than it is for providers in other medical specialties, who tend to work in the private sector. As an example, according to the National Council for Behavioral Health, a registered nurse working in mental health earns $42,987 as compared to the national average for nurses of $66,530.

Valuing Work-Life Balance

But financial factors are not the leading reason that medical students are avoiding primary care, Mitchell said. In surveys of medical students conducted by AAMC, students valued “work-life balance” more than money when they were choosing their specialties. Because primary care often involves long hours and night and weekend calls, it is far less desirable to this generation of students.

“Half of the physicians in training are women,” Mitchell said. “You find more of them are looking for a career that might be compatible with part-time hours, that don’t involve being on call. Men are more engaged in child care today, and they have similar concerns as they consider their career choices.”

A steady stream of negative attention has made medicine in general a far less attractive career choice than it once was, according to Rosenberg of the National Council for Behavioral Health. Insurance headaches, pricey technologies, long hours and the risk of liability have convinced many talented students to eschew medicine as a career choice.

“Nowadays,” Rosenberg said, “the best and the brightest are talking about becoming investment bankers or going off to Silicon Valley.”

Dwindling Dentists

To some extent, dentistry created its own problem. Richard Valachovic, president of the American Dental Health Association, said today’s shortage of dentists can be traced to the closing of seven dental schools in the 1980s and 1990s. In 1980, he said, the United States produced 6,300 dentists. Ten years later, the number was down to 4,000.

Why did the schools close? “There was a perception that we had conquered dental disease,” Valachovic said. “Kids weren’t getting cavities anymore so we thought we wouldn’t need as many dentists.” Dental health did improve, he said, but not for the poor and those without insurance.

Twelve new dental schools — smaller than their predecessors — have opened since 1997, Valachovic said, so the U.S. is back to graduating 5,700 dentists a year. But the ACA has made pediatric dental care coverage a requirement for all insurance, which will extend benefits to as many as 8.7 million children by the year 2018. Demand will far exceed capacity to produce dentists for years to come.

Some Cause for Optimism

Despite the shortages, many believe that new technologies will extend the reach of medicine in ways that will ameliorate the problem.

For example, health care professionals can serve more people by using Skype or other telemedicine technologies to examine, treat and monitor patients. Similarly, patients can be fitted with electronic devices that remind them to take their medications and provide other guidance about their conditions. These and other technologies are already keeping patients out of hospitals and doctors’ offices.

Changes in the way medicine is delivered, such as the use of “medical homes” and “accountable care organizations” to better coordinate patient care, are also expected to improve efficiency and keep patients out of the hospital. These organizational changes will make primary care physicians more important than ever, which might make primary care a more appealing — and lucrative — career choice.

A more controversial idea is to allow nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists and dental aides to do some of the work usually reserved for doctors and dentists. Many states have passed such legislation while others are eyeing similar measures. The Pew Charitable Trusts has supported such efforts.

The American Dental Association, however, opposes allowing mid-level dental workers to perform some of the functions of dentists, such as routine preventive and restorative work. The organization, which represents 157,000 dentists, questions federal data on a dentist shortage, suggesting the problem is more of an uneven distribution of dentists.

Some groups representing doctors are resisting similar efforts to allow nurse practitioners to, for example, write prescriptions and admit patients to the hospital. But many believe the trend is unstoppable.

“Health care is not a zero-sum game where there’s a limited amount of care to be given,” said Polly Bednash, the head of the American Association of Colleges of Nursing. “If there’s more care needed than we can deliver in the world, we have to decide who else can provide quality care.”

A Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) is a geographic area or population group with too few health care providers to serve people’s medical needs. Under federal guidelines, there should be no more than 3,500 people for every one primary care provider; no more than 5,000 people for every one dental provider; and no more than 30,000 people for every one mental health care provider. The graphs below show the percentage of the population in each state that lives in an HPSA.

primary.jpg