The term “contactless” has become increasingly popular in recent months, thanks to the resilience of COVID-19. Demand for digital and no-touch services has grown by 20 percent in the U.S., according to the consulting firm McKinsey, and governments have responded, ramping up online portals and services, rolling out contactless transit systems, enabling remote visits by social workers, and enlisting chatbots to support surging demand in call centers. But governments’ rapid response to the COVID-19 pandemic goes far beyond digital payment and delivery of services. Remote work, virtual hearings, digital identities and other technologies all are reshaping how governments operate and interact with their constituents in ways that will long outlast the pandemic.

“Without a doubt, COVID-19 accelerated by some years the future of government — and especially digital government,” says William D. Eggers, executive director of Deloitte’s Center for Government Insights. “We will look back at this as one of the real inflection points in modern history for government management, operations, and service delivery in particular.”

But government leaders face new challenges as they seek to maintain momentum beyond the pandemic. Here are 10 areas to focus on:

1. Leadership commitment. “Executive Directive No. 29” doesn’t have much of a ring to it. But Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti’s “Contactless and People-Centered City Initiative,” issued in late August, is nothing less than a long-term call to action for the city’s government.

“As our physical doors start to reopen in the future, we will also expand our digital doors to provide services anytime, anywhere, and to all,” the directive says, pointing to “widely” varying disparities in digital services across the city’s departments.

The pandemic has increased the city’s ongoing digitization efforts as much as threefold, says Los Angeles CIO Ted Ross. And throughout the country, governments’ response to COVID-19 has been a success story in many ways. Governments that had previously made investments in digital delivery were rapidly able to add additional services. Those which had already launched telework programs were able to scale up rapidly. In some areas, growth has been exponential. For example, the rapid adoption of telemedicine has accelerated anticipated road maps by as much as five years, according to Eggers.

But maintaining momentum has historically been a challenge for governments, Ross says. “What often happens is you have some early entrances and make headway, and then things slow down,” he says. “The daily whirlwind of government makes it hard to make progress. COVID has forced the conversation.”

As the pandemic abates, it will take continued leadership to drive sustained change, according to Eggers. “You have to be proactive about making this happen,” he says. Pointing to how President Obama became personally involved in promoting healthcare.gov following passage of the Affordable Care Act, he adds, “you need to make it a top priority and invest political capital into it.”

2. Thinking beyond digital delivery. While Sanford’s City Hall has reopened to the public — and automated responses to incoming phone calls say the government is “Sanfording safely” — the reality is that few developers ever wanted to drive downtown to file permits.

Even so, it took the pandemic to finalize a process for online submission and approval. “We’d been working on that before, but COVID made it where that’s how we do it,” says Bonaparte. In similar fashion, San Diego’s development services division launched in October a “virtual counter” featuring Zoom consultations with city staff and a clear message — “no more paper accepted.”

The reality, however, is that many other government services can’t be delivered digitally. The same forces that have driven solutions to date should prompt leaders to think about ways to reduce friction points. Building inspections, for example, often require an inspector to make an in-person visit, but much of the groundwork and subsequent follow-ups can be conducted online, and recreational activities can be scheduled digitally and followed up with surveys to monitor the quality of service.

“You can’t conduct a swim lesson virtually, but the vast majority of what we do as a government can be done digitally or substantially enhanced digitally,” Ross says. “Digital isn’t automating a paper-based workflow. It’s taking culture and process and applying them to the new society we’re seeing through technology.”

3. Developing digital identities. An essential — and still largely missing element — to improving digital government, unified digital identities allow citizens to use a single login to access services across all departments and services, breaking down the silos that have plagued digital efforts to date. The United States “is far behind many countries in that regard,” Eggers says.

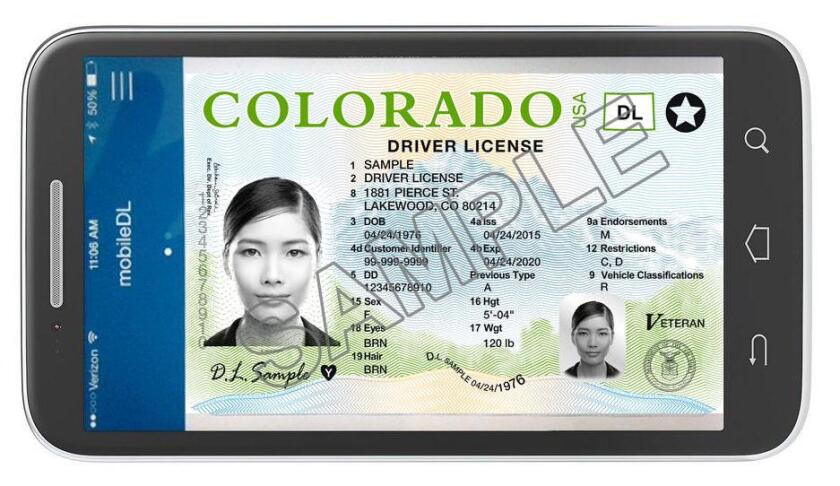

myColorado digital identification (Courtesy of Colorado.gov)

In Los Angeles, the city’s Angeleno Account has now been implemented for the business virtual assistance network and is going live across the city’s 311 services, representing the collective work of dozens of city departments, according to Ross. And the myColorado Digital ID, which already can be used as a legal form of personal identification, could soon be accepted as proof of identity by law enforcement agencies. Ultimately, that could mean that smartphones could supplant physical driver’s licenses.

4. Refining remote work. Many state and local governments had invested in technology to allow employees to work remotely before the pandemic, but the rapid shutdown of government buildings forced massive scaling. Los Angeles, for example, went from “a few hundred people” to nearly 18,000 remote employees in a matter of weeks, says Ross.

“It’s gone better than most would have predicted ahead of time,” Eggers says. Fears about productivity losses have proven largely unfounded in and out of government. Nearly two-thirds of business leaders (63 percent) had concerns about productivity and remote work before the pandemic, but just one-quarter (26 percent) did following the shift, according to a survey conducted by PwC. It’s results like this that have prompted public- and private-sector employers to look to a future where telecommuting remains the norm.

“The bell has rung. You can’t unring the bell,” says William Shields, executive director of the American Society for Public Administration (ASPA).

While much has been written about the challenges of supervising and measuring the performance of remote workers while providing needed flexibility, Shields says government workers also need to be empowered to do something that’s not always common in the public sector — navigate rapidly changing scenarios.

“Accepting the uncertainty of the times and managing to that uncertainty is something government professionals are increasingly needing to do,” he says. “That involves breaking employees of the mentality that they have to know everything… and to encourage them to use informed intuition based on their prior knowledge and experience.”

Following the pandemic, government workplaces will become even more hybrid and “adaptive,” says Eggers. “Systems and processes we have today designed for a pure office model will have to be redesigned — performance management, supervision, teaming, all those different things work differently,” he says. But workers will also have new supports — for example, AI-powered chatbots will be deployed in ways that elevate more complex cases to human employees. “Human-to-machine collaboration will optimize results and play to innate strengths,” Eggers predicts.

5. Rethinking public meetings. Many governors and attorneys general rapidly issued executive orders or rulings at the onset of the pandemic that temporarily relaxed open meeting laws to allow governing bodies to convene remotely. By April, more than 40 states had made such changes, and some governments found that shifting public meetings online actually boosted citizen interactions.

State governors meeting on Zoom.

“We found the convenience of [attending] meetings at home increased engagement in ways we wouldn’t have imagined,” Mick Renneisen, deputy mayor of Bloomington, Ind., whose city held two well-attended online forums on a major redevelopment project, said during a summer webinar.

However, the long-term impact remains unclear. Changes to open meetings laws to date have largely been tied to the COVID-19 emergency, and civil liberties groups have raised concerns about the impacts on public access in some jurisdictions.

6. Addressing the digital divide. Governments have learned that meeting constituents where they are during the pandemic involves a combination of challenges — older constituents may prefer face-to-face interaction, and the unbanked may need to pay in cash. But what has been revealed in stark relief after schools shifted to remote learning is how many families lack Internet access at home.

As many as 24 million households nationwide lack reliable and affordable Internet access, with the largest numbers in rural areas, according to McKinsey. Many governments and their school districts are coordinating private- and public-sector efforts to provide low- and no-cost options for students and citizens, such as L.A.’s Get Connected initiative and San Jose’s Digital Inclusion Fund, which targets the city’s 95,000 residents without Internet access.

Ross argues that efforts to connect citizens go beyond accessing school and government services. Instead, it’s a vital part of participation in the broader economy and society. “The world around them is increasingly more digital — job applications, schooling, and entertainment,” he says. And approaching digital government with what Bonaparte calls “an equity lens” goes beyond whether residents can access digital services; it also touches on thinking about all types of government communication.

“The newspaper isn’t going to get everybody. Online isn’t going to get everybody,” he says. “We need to be doing it multiple ways.”

(Ben Dalton/Flickr)

7. Maintaining options. While digital services have largely been ramped up by necessity, it’s important to ensure that citizens continue to have other options. Maintaining multiple options can be part of a longer-term strategy, as has been the case with Los Angeles’ 311 service, which has seen digital usage grow to one-third of all interactions in recent years. “As we digitize these solutions and they become readily available, they become the option of preference,” Ross says.

8. Privacy and security. Headline-grabbing cyber and ransomware attacks are coming at a time when more government operations are reliant on digital systems — and more employees are accessing them from home. Beyond the threat of cyberattacks, the remote delivery of services requires governments to think in new ways about ensuring that privacy laws are being followed — for example, when a public health official is conducting a patient interview from home and other family members may be in earshot. And efforts to implement next-generation contactless technology, such as the facial recognition systems now being deployed to streamline security and boarding processes in airports in Houstonand Atlanta, could fall afoul of legislation banning their use within other jurisdictions.

9. Budgeting priorities. As government leaders await the full fiscal impact of the pandemic, experts point to how cutbacks following the dot-com crash nearly two decades ago slowed government adoption of technology for years. “I hope technology is the last place governments cut,” says Eggers. “There’s a realization that this is about services, not technology, and we need to invest more and find ways to do so.”

10. Look ahead to “no-touch” government. Governments’ success in maintaining services during the pandemic has “made the public more conscious and aware of the impact public servants have on every minute of their lives, regardless of how those services are delivered — in person or virtually,” Shields says. Looking forward, the opportunity will shift to making those services automatic.

Instead of “contactless,” think “no-touch,” Eggers says. In other countries including Finland and Austria, the focus is increasingly shifting to proactive service delivery — automatically delivering benefits during major life events such as when a child is born, a loved one dies, or a company lays off its workers, all without requiring constituents to apply for services.

These changes shift governments “from doing digital to being digital,” he says. “It’s where very few things governments are going to do that aren’t going to be digitally enabled and powered. It does become very much a core competency.”