A report published in September by UN Climate Change concluded that even if all nations actually achieved their stated commitments to reduce CO2 emissions by 2030, these emissions would still be on track to increase 16 percent as compared to 2010 levels. It highlighted an urgent need for either a “significant increase in the level of ambition” of commitments from nations or a “significant overachievement” of the goals they have set.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), emissions must reduce by 45 percent by 2030 for warming to be limited to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Preventing 2 degrees Celsius warming within this time frame, the outer limit deemed tolerable by parties to the Paris Agreement, would require a 25 percent reduction.

An analysis by the International Energy Agency (IEA) published last week estimated that if the most recent national commitments are taken into account, it’s possible that warming could be limited to 1.8 degrees Celsius by the end of the century. The IEA described this as a “landmark moment,” the first time that governments had set targets that could keep global temperature rise below 2 degrees Celsius.

(Christopher Furlong/TNS)

Not Far Enough

In the past year, communities in the U.S. have had firsthand experience of the impacts of warming, from heat domes, wildfires, hurricanes and floods to severe drought. In light of this, it might not be surprising that half of those participating in an NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll believe that the country’s policies “don’t go far enough” to prevent climate impacts.

Led by activist Greta Thunberg, tens of thousands of protesters last week marched in Glasgow, demanding that countries push harder to mitigate climate change. Des Moines Mayor Frank Cownie, a member of a delegation from the United States Conference of Mayors attending COP26, understands their concerns. He attended the Copenhagen climate conference in 2015, excited that world leaders agreed to declare that a problem existed but discouraged when their declaration was not accompanied by substantive commitments.

“We at the local level suffer the consequences of their actions or inactions,” he says. “We all have to work together to achieve success — at the heads-of-state level, the national level, all the way down to subnational levels of government.”

While the political climate might vary from state to state, communities throughout the country are already experiencing climate impacts. The things that need to be done to reach emission goals have been known for decades; the barrier isn’t know-how as much as the ratio of political will to inertia. Is there anything in Glasgow that might be new to local governments?

Global Pledges, Local Responsibilities

In recent years, the role of methane in warming has received increased attention, not only because it is an especially potent greenhouse gas, but because there are straightforward strategies for reducing emissions. Early in COP26, it was announced that more than 100 nations had joined a Global Methane Pledge, agreeing to take voluntary actions to help reduce global methane emissions.

The target, which is global rather than national, is a 30 percent reduction from 2020 levels by 2030, which in itself could reduce warming by 0.2 degrees Celsius by 2050. The countries already supporting the pledge account for more than 40 percent of global emissions.

“The methane pledge has been important and can be impactful,” says Angie Fyfe, executive director of ICLEI USA. “It’s a demonstration of the understanding that methane is a greenhouse gas that we can affect at a systemic level.”

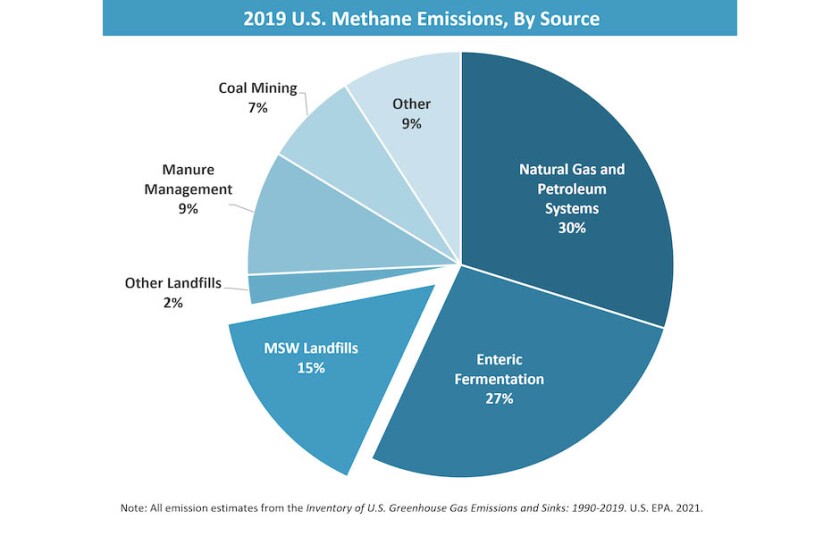

The warming potential of methane is about 90 times that of an equivalent amount of CO2. Emissions from gas and petroleum systems and cow burps account for almost 60 percent of U.S. methane emissions.

Landfills are responsible for 15 percent of U.S. methane emissions. ICLEI works with local governments to reduce these emissions, and the heightened attention on methane will bring new urgency to this work.

A handful of states have addressed this by banning organic waste from their landfills. Others are capturing landfill methane and using it to generate energy, a net benefit. (Food waste can also be converted to an energy source, biogas, through anaerobic digestion.)

Another well-received pledge made in the first week of COP26 is a promise to preserve the “lungs” of the earth, which release oxygen and store CO2, by ending deforestation by 2030. “That certainly relates to cities and counties here in the U.S. who control forests and urban tree canopy and make decisions to sequester carbon in trees inside and outside our forests,” says Fyfe.

(TNS)

Building Standards and Climate

The built environment is on the COP26 agenda during its second week. Building operations and construction are responsible for about 40 percent of global CO2 emissions.

Energy codes for residential and commercial buildings provide an evidence-based foundation for reducing emissions from building operations. These codes can ensure efficient, low-emission buildings are business as usual and are likely to support achievement of the targets set at COP26.

“When we pulled out of the Paris climate agreement, you saw all these cities and states coming together and saying that they’re still committed to its goals, says Ryan Colker, vice president of innovation for the International Code Council (ICC). “But at the same time, there’s a disconnect between those higher-level policies and where states and localities are relative to their energy code adoption, despite the significant impact that buildings have on energy use and greenhouse gas emissions.”

Colker, who traveled to COP26 to press this case, recognizes that the federal government can’t mandate code adoption, but believes federal grants and technical assistance could speed the process. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 included $3.1 billion to help states adopt and implement codes that met or exceeded the 2009 International Energy Conservation Code, leading to an uptake in adoption, he says.

“I think we’ll see similar types of approaches moving forward with the reconciliation package and the infrastructure package,” he says. “I think that’s going to be the main avenue to help advance state and local adoption.”

The increased frequency and severity of climate disasters have made adaptation and resilience major themes at COP26, and building codes embody best practices for building safety during extreme weather events. For example, storms in Gulf states such as Florida have already forced reconsideration of building codes, but risks from floods and wind — not to mention fire — are growing throughout the country.

Real-world events are forcing the building community to grapple with the reality that the requirements for building safety aren’t the same in a warming world. “If we’re building the buildings for 50 or a hundred years, the risks they are going to face over that lifetime are likely to be different than what we’ve seen in the past,” says Colker.

(DANIEL SLIM/AFP/TNS)

Challenges to Federal Authority

Steady progress toward preventing the worst effects of warming depends upon coordination and cooperation, not just between countries but between state, local and federal efforts. Competing economic interests, disinformation, political theater and failure to make the science behind climate change broadly understood, among other factors, already thwart cooperative effort.

As if this weren’t enough, the Supreme Court has agreed to hear several cases challenging the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) authority to enforce Obama-era emission standards for power plants under the Clean Air Act.

One sort of ruling could result in no change in the status quo. But other possibilities could result in varying degrees of disruption to any effort to align federal and state climate action.

At issue is the “major questions” doctrine, the notion that in general, Congress does not intend to give agencies authority over matters of “vast economic or political significance.”

The court could reject the notion that the EPA has exceeded its authority under the Clean Air Act. However, it could also rule that even though, hypothetically, the EPA might have the right to do as it has done, the statute itself doesn’t authorize it with enough clarity. Or it could issue a ruling that suggests that the Constitution does not allow Congress to give such powers to agencies, even if a statute is very clear about what it is asking them to do.

It’s not hard to see how much confusion a ruling in this direction could create, not just about climate mandates from the federal government, but virtually any environmental statute under which federal agencies conduct regulatory activities.

This wouldn’t inherently mean the end of federal authority to regulate, says Kirti Datla, director of strategic legal advocacy for Earthjustice. “But it will generate a lot of challenges that maybe wouldn’t have been brought before and those challenges will be more likely to gain traction.”

There’s no small irony in the fact that although some of the current petitioners are from the coal industry (along with Republican legislators from coal-producing states), major power companies filed a brief asking the Supreme Court not to take the case.

“They explained that it would be, basically, a waste of time to look at these older regulations because the electricity sector had already met the targets in the Obama-era regulation a decade ahead of the schedule in that regulation, even though it never even went into effect,” says Datla.

(Justin Sullivan/TNS)

A Lot of Work

After the 2015 Paris agreement, ICLEI published an analysis of the emission reductions local governments would have to achieve to do their part in limiting temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, targets that seemed ambitious at the time. Recently, ICLEI made new calculations for about 150 communities and concluded that by 2030, the average community needs to reduce emissions by 63 percent.

“I look at those earlier targets now, and none of them is even close to 63 percent,” says Fyfe. “We’re getting more knowledgeable about where we are and where we need to be.”

Fyfe has been making presentations to local governments about its revised estimates and the science behind them. Recently, this took her to a mountain town in her home state of Colorado and a group of citizens, local leaders and elected officials.

She gave them the 63 percent number and I asked if it seemed scary. “I’ll tell you what’s scary,” came one memorable reply. “What’s scary is when I see plumes of smoke coming over the Ridge and I know that my house might be next — 63 percent makes me realize what we need to do and gives us the drive and desire to make that happen.”

Twenty years ago, the conversation focused on changes governments would need to make by 2100, says Mayor Cownie. But severe climate impacts have arrived much sooner than imagined. It’s now apparent that failure to harness activities, thoughts and best practices by 2030 could lead to effects that could last hundreds, if not thousands, of years and make it much harder to sustain populations on the planet.

“We haven’t seen this kind of emergency in the history of human existence,” he says. “We have a lot of work to do.”