Methane doesn’t last as long in the atmosphere as CO2, but its power to cause warming is much greater. “Methane has about 90 times as much warming potential as an equivalent amount of CO2 released in the atmosphere,” says Riley Duren, a research scientist at the University of Arizona.

Methane emissions are accelerating faster than at any time since record-keeping began in the 1980s. This trend continued even during the economic shutdown caused by the pandemic, according to measurements by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

One of the more notable outcomes from COP26 was the Global Methane Pledge, a commitment to reduce methane emissions from 2020 levels by at least 30 percent by 2030. More than 100 countries have signed on. According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), achieving this target alone could prevent .2 degrees Celsius of warming by 2050.

Several states in the U.S. are including organic waste reduction in their climate plans. But none have attacked the problem more aggressively than California, home to twice as many landfills as every other state but Texas and more buried trash per capita than every state but five.

Organic Waste and the Circular Economy

Organic materials account for half of what ends up in California landfills, according to CalRecycle. A program Duren leads, that measures emissions with high-altitude imaging, found that landfills account for as much as 46 percent of the state’s methane inventory.

As of January 2022, it became mandatory for all jurisdictions in the state to provide organic waste collection services to all businesses and residences. They must process the collected waste using anaerobic digestion and composting.

In addition to its climate impact, SB 1383 is a step toward a different way of doing business, says Rachel Machi Wagoner, the director of CalRecycle. “Gov. Newsom and the Legislature are really looking at implementation of this law as foundational to building the circular economy here in California.”

In a circular economy, products are designed so that they don’t produce waste or pollution and can be used indefinitely, either as they are or as raw material for new products. Achieving this with consumer goods, such as automobiles or the millions of products that fill stores, is one thing, but the means already exist to make discarded food into something new and valuable.

Recycling aims to convert waste to material that can be used again. But only about a quarter of the material collected for recycling is made into something new. Moreover, products made from recycled material lose value each time they are processed, eventually becoming waste.

The technologies that could make organic waste collection waste “circular” are well established. It can be composted, returning the nutrients and bacteria in it to the soil. Compost also absorbs carbon from the atmosphere.

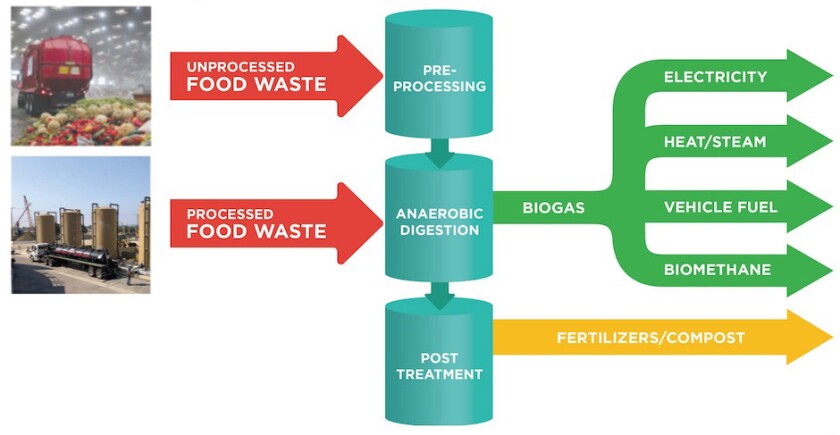

Food waste can also be processed in an anaerobic digester, a sealed container in which the food is broken down by bacteria. The methane released in the digester can be burned to generate electricity, or used to make biogas or biodegradable plastics. The process also results in “digestate” material that can be used as fertilizer or soil conditioner. Spread on soil, the digestate absorbs carbon.

California will need more infrastructure to meet its 75 percent diversion goal.

Getting to 75 Percent

The 50 percent waste reduction target set for 2020 was not met, says Machi Wagoner. In fact, the amount of organic waste sent to landfills was above the baseline. COVID-19 brought challenges to local government that could never have been anticipated, and a bill was passed in 2021 to provide some breathing room by allowing jurisdictions to submit a notice of intent to comply with the new regulations, accompanied by a timeline of action items.

“We have a lot of work to do to get to our 75 percent goal by 2025,” says Machi Wagoner. “I'm very optimistic because the 2020 goal was before the regulations went into effect, while many local governments were still building out their systems.” This year, her priority will be helping jurisdictions work out their infrastructure needs, including how materials will be processed, as well as what it will take to get their programs online quickly.

Collection is the starting point for all of these efforts, and the law allows jurisdictions to provide either source-separated or single-container waste collection, with prescribed colors for curbside containers. Many jurisdictions have already incorporated three-bin systems, with a green bin for yard waste. Machi Wagoner expects these to be used to collect other organic material from residential customers in most cases.

Just under 200 local jurisdictions already have some level of food and yard waste collection in place, she says. “In the spring, they will all be reporting to the state what their capacity plan is, and that will give us a better sense of where state investment and state assistance could be built out.”

When the 75 percent diversion goal is met, CalRecyle estimates about 18 million tons of organic waste will need to be processed through composting, anaerobic digestion or chipping and grinding. Existing infrastructure can accommodate about 10 million tons. Co-digestion at existing wastewater treatment plants could handle about half of the food waste collected.

In 2021 CalRecycle was allocated $20 million for grants to expand food waste co-digestion at water treatment plants. This is a first step toward the investment necessary for these facilities to handle this much food waste, estimated to be in the $1 billion range.

The 24 independent special districts that make up the L.A. County Sanitation Districts collect and treat wastewater from 5.6 million people. The agency has been using its digesters to recycle food waste for about eight years, and the program it has developed gives strong evidence of the “circular” benefits that are possible.

(LA County Sanitation Districts)

Nothing is Truly Disposable

Los Angeles County — the nation’s largest county by population — generates 21 million tons of waste each year, says Wendy Wert, senior engineer for the L.A. County Sanitation Districts. Close to half of it, 9 million tons, goes to landfills, the equivalent of 45,000 blue whales, she says. Of this, about 1.5 million tons is food waste, an average four tons per day.

“There’s energy potential there, but there’s something else at play that’s bigger than the energy potential,” says Wert. “It’s looking at greenhouse gas emissions.”

There are 24 anaerobic digesters at the Districts’ Joint Water Pollution Control Plant (JWPCP). The Puente Hills Materials Recovery Facility (PHMRF) converts an average 35 tons per day of food waste into slurry and is capable of handling as much as 165 tons per day. The slurry is carried by trucks to JWPCP and added to its digesters along with wastewater.

Some of the resulting biogas is sent to a power plant in Carson, Calif., and is converted to electricity that runs the treatment plant. The 20 megawatts of power it generates meets 95 percent of the plant’s needs and avoids $20 million in yearly electricity costs. Some of the gas is purified for use as fuel by natural gas vehicles, available at a sanitation district fueling station that is open to the public, including government fleet vehicles.

(LA County Sanitation Districts)

The solids that remain after digestion can be used for composting. “Those nutrients are then being recovered as well,” says Wert. All in all, she says, the outcomes that are being achieved reflect the best use of available technologies.

It’s a mistake to consider anything as truly disposable, says Wert, who also serves as vice president of the American Academy of Environmental Engineers and Scientists. “Everyone’s community is somewhere, whether it’s a creature or a person — you can’t really dispose of anything unless you leave the planet.”

(SBWMA)

The Yin and Yang of Processing

Currently, the state doesn’t know how much organic waste end up in landfills, and won’t know until the state starts recycling in earnest, according to Yaniv Scherson, COO of Anaergia, a company that produces clean energy from waste. Right now, jurisdictions in California are focused on developing the plans they are required to submit by spring 2022.

One decision that needs to be made is whether organics will go to digesting or composting. “Compost sites are great for green waste, but they’re not so great for food waste — you can’t compost food waste by itself.” says Scherson. “There’s a yin and a yang between the wastewater plant digesters, which are phenomenal for food waste, and the compost sites, which are phenomenal for yard waste.”

SB1383 also includes a procurement requirement, mandating that each jurisdiction purchase products resulting from organic waste recovery according to targets based on their population. This can range from mulch to energy. It’s another layer in the planning process, says Scherson. For example, populous cities may not have enough parks to fill with the compost they produce, but could consume the energy that is generated from the waste.

There are more than 150 digesters at California wastewater treatment plants. These are publicly owned assets that could be expanded or retrofitted and comprise the bulk of the infrastructure required for processing food waste. Scherson’s company, which designs and builds equipment and facilities, has played a significant role in moving this forward.

Even after decades of recycling, about 25 percent of what goes into recycling bins in the U.S. is too contaminated to recycle. High levels of contaminated and nonrecyclable goods in “recyclables” sent to China eventually led the country to ban waste imports. It can’t be assumed that citizens and businesses will do a good job separating material according to new guidelines for organic waste.

A processing approach that sidesteps the complexities of separating contents of containers that include organic waste is in place in some jurisdictions. An extrusion press compresses waste from these containers, capturing 90 percent of the organic material in a slurry that can be transported to a digester. Solid material is separated and continues its journey to landfills or recyclers.

The South Bayside Waste Management Authority (SBWMA) is a joint-powers authority formed by 11 jurisdictions in the San Francisco Bay Area. SBWMA is piggybacking on its existing wastewater treatment system by using an extrusion system to create what Hilary Gans, its senior operations and engineering manager, describes as a “food waste smoothie.”

“There’s a lot of experimentation going on right now because nobody has the silver bullet,” says Gans. “We’ve decided to try this system, and the wastewater treatment plant likes it — they like it, what can I say?”

In California, a number of wastewater plants create electricity for their operations with the gas from their digesters. As they continue to receive new inputs from food waste, it’s possible that some could become net exporters of electricity, generating local power for local use, Gans says.

Eventually, he hopes to see his agency fuel its trash fleet with biogas. “What we’re talking about here is the industrialization of a biological process to efficiently turn food waste into a fuel or power.”

(Kent County DPW)

Trash as Opportunity

California isn’t the only state to focus on food waste. In 2021, more than 50 bills relating to it were introduced in 18 states. A number of states have already passed bills designed to keep food out of landfills, including Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Washington.

In 2016, the Kent County, Mich., Department of Public Works (DPW) launched a campaign with a goal of reducing waste going to landfills by 90 percent by 2030. An economic assessment determined that the more than 200,000 tons of mixed organics going to its landfill each year, if converted to compost, could be worth as much as $9 million.

Darwin Baas, Kent County’s DPW director, has long found it hard to accept the reality of what is thrown away as trash. “You steel yourself against what you see coming in,” he says. “Every time I’m up at the landfill, there is so much good material — why in the world have we made the decision that it has no value?”

In the 1930s, drivers would go directly in homes and collect kitchen scraps from metal containers to transport to piggeries, according to Baas. As jurisdictions transitioned from dumping to the modern era of landfills, convenience dictated that everything was tossed into trash cans.

Half of everything going to the Kent County landfill is organic, and once it goes into a landfill, says Baas, its value is lost forever. “If you have a decent landfill gas system, you can generate electricity, but that’s not the end of the story; the story is the nutrient value, the fertilizer value.”

Kent County is home to orchards and land where crops including corn, soy, wheat and berries are grown. It makes sense to extract the natural resources in food waste for the betterment of these activities, he says.

Rather than building a new landfill, the DPW has decided it will “reimagine trash” by setting aside 250 acres of land for a sustainable business park open to companies that can convert waste that would otherwise have gone to a landfill into usable, valuable products. It will include a mixed waste processing facility and an anaerobic digester.

(Anaergia)

Neglected Renewable Energy Source?

Like other fossil fuels, natural gas is not considered to be “clean” or “renewable.” But biogas made from the methane created in biodigesters using organic waste is considered to be a renewable fuel.

Renewable natural gas (RNG) is well accepted as a climate-friendly fuel source for heavy-duty vehicles or industrial applications requiring very high heat, but does it have any other place in long-term climate strategies?

It's been estimated that the country’s organic waste streams could yield RNG equivalent to about 7 percent of natural gas consumption. Even if this production capacity could be reached, it would not amount to a “solution” to climate change in itself, but it has the potential to aid in the reduction of emissions.

States with deep greenhouse gas reduction goals are starting to look more seriously at how they can use their organic waste streams, says Sam Wade, director of public policy for the Coalition for Renewable Natural Gas.

CO2 is released when RNG is burned, but the carbon has moved from the atmosphere to plants, to animals and food chains and, eventually, back into the atmosphere. This “biogenic” carbon doesn’t cause a net increase of carbon in the atmosphere.

The place of RNG in the energy mix can seem small compared to the current size of the country’s existing gas system, but as the push to phase out natural gas gains momentum and states like California expand the recycling of organic waste, RNG production capacity will increase, and its importance to the energy transition could shift.

A database maintained by the Argonne National Laboratory includes several dozen projects upgrading biogas for pipeline injection at stand-alone digesters and waste treatment facilities. Existing sources could replace 25 percent of diesel fuel; potential production has been estimated to be 10 to 20 times greater than current production.

Related Articles