In motor vehicle regulation, the pandemic accelerated what has been a gradual transition to serving customers remotely. “The evolution of mobile driver’s licenses and the recognition of being able to do transactions without exchanging a physical document certainly fits within that,” said Ian Grossman, vice president of member services and public affairs for the American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators (AAMVA). “Being able to empower customers to have a credential that they can use in a transaction where they’re not passing back and forth a physical document has been further accelerated by the pandemic.”

Arizona rolled out its mobile driver’s license (mDL) app in March 2021. Eric Jorgensen, director of Arizona’s Department of Transportation, is leading his state’s nascent mDL initiative. He wants to make clear, however, that the state has its sights set on something much bigger.

“I actually hate the term ‘mDL’ because it doesn’t recognize the power of what we’re doing here,” he said. Arizona calls its app AZ Mobile ID. “The whole concept is that we’re providing a way to remotely authenticate a person, to provide a trusted digital identity that doesn’t exist today. Once we provide that, we’re opening doors to enhanced government services. Also, the government can play a key role in facilitating commerce, providing a better citizen experience and providing for the security of that citizen — that goes way beyond what a driver’s license is about.”

A 2020 white paper by an industry consortium called the Secure Technology Alliance highlights some of the reasons states are intrigued by mobile IDs, described as a “new way of cryptographically verifying identity.”

“The person who holds the mDL controls what information is shared and with whom,” the report noted. “In addition, mDLs support more efficient and secure transactions. For in-person transactions, electronic authentication can give the mDL verifier confidence in the presented ID without requiring specialized knowledge of the hundreds of card design and security features applicable to the driver’s licenses (and their variants) that are issued by 56 states and territories. The mDL can also eventually be used to increase security for online purchases and interactions.”

10K Delaware residents downloaded the state’s mobile driver’s license app in six weeks since it launched an information campaign.

“There are a lot of government agency use cases where you would use your driver’s license or state ID to prove that you are who you say you are,” said Russell Castagnaro, director of digital transformation in the Colorado Governor’s Office of Information Technology. “This is all foundational work. We’re going to prove it out with the DMV, and then with taxation, and then spread it out across the other agencies as quickly as possible.”

The myColorado app, which has been downloaded by approximately 100,000 Colorado citizens, provides access to COVID-19 resources, to Colorado PEAK (Program Eligibility and Application Kit) to apply for benefits, and to DMV services and state job opportunities. It also allows citizens to store digital vehicle registrations and proof of insurance in the app wallet. Citizens can leverage it to get a version of their fishing license, and the state will soon be adding other parks and wildlife licenses. The state also is working on a revocable consent model to be used in the health-care space, Castagnaro added.

Colorado State Patrol (CSP) troopers began accepting digital IDs on Nov. 30, 2020. The state is engaging with local police departments and sheriffs’ offices as well.

These mDLs are in their very earliest stages of use. Until more police, businesses and other state agencies invest in the technology to read mDL data, the appeal to citizens will be limited. States are essentially facing a chicken-and-egg problem. People don’t get mobile driver’s licenses because there aren’t many places that accept them, and businesses and public-sector organizations don’t invest in the technology to read and process them because not many people have them.

“We worry about that a lot,” said Jana Simpler, director of the DMV and toll operations for the Delaware Department of Transportation. “Even though this rolled out for us statewide on March 9, we want to keep the enthusiasm for mDL growing,” she noted, adding that the state began an information and education campaign in May. “In the most recent data, over 10,000 people have downloaded the app in about a month and a half.”

Delaware is also seeking to convince businesses to accept mDLs. The majority that have signed up so far have been restaurants or hospitality businesses that sell alcohol and tobacco products. They are seeing some interest from casinos and the gaming industry as well.

“The general philosophy is that once we get these into more people’s hands, and they’re trying to use them, the relying parties will recognize the need to invest in the infrastructure to read them,” AAMVA’s Grossman said. “It’s not unlike when chips on credit cards first came out. We all started to get the credit cards, but when you went to the store, they didn’t take them. But it didn’t take that long to move from that to where we are now, which is that your chip can be used pretty much anywhere.”

ROLE OF THE CIO'S OFFICE

Because of the potential widespread impact of mobile ID initiatives, some of them are being led by technology officials like Colorado’s Castagnaro. In other states, DMVs or DOTs are taking the lead role.

One person working at the center of the mobile ID movement believes state CIOs should form closer partnerships with DMVs. Matthew Thompson is senior vice president for civil identity, North America, at IDEMIA, a company that partners with 34 state DMVs on physical driver’s license solutions. The company has partnered with three states on mDLs so far. He says that governors and state CIOs should look at their DMV not just as an agency that provides driver and vehicle services, but as one that can operate as an identity management bureau for the entire state and provide verification services to enable e-government.

“State CIOs need to better understand the [role] that trusted identity plays in driving their entire digital transformation,” Thompson said. “They have a built-in identity bureau in their state that has a system of record that provides a route of trust that other agencies can benefit from immediately. What shined a light on the massive deficiencies and gaps we have here is rampant unemployment fraud, which has occurred to the tune of $62 billion. By not solving the identity challenge for digital transformation, the consequences are dramatic.”

States like Arizona and Delaware have worked with IDEMIA on physical driver’s license infrastructure and have extended those relationships with the company for mDLs, too. In Delaware, the Department of Technology and Information has been involved from day one as well, Simpler said. “I’m grateful for those IT folks who made sure that we got the i’s dotted and t’s crossed … as well as ensuring that we followed more global ISO standard needs.”

Although it works with companies such as Ping Identity for login and multifactor authentication, Colorado has a dedicated internal team working on the core components of myColorado. “I never really liked the idea of having a third party being the only one who writes how a system works when it’s your own data,” Castagnaro said.

STANDARDS

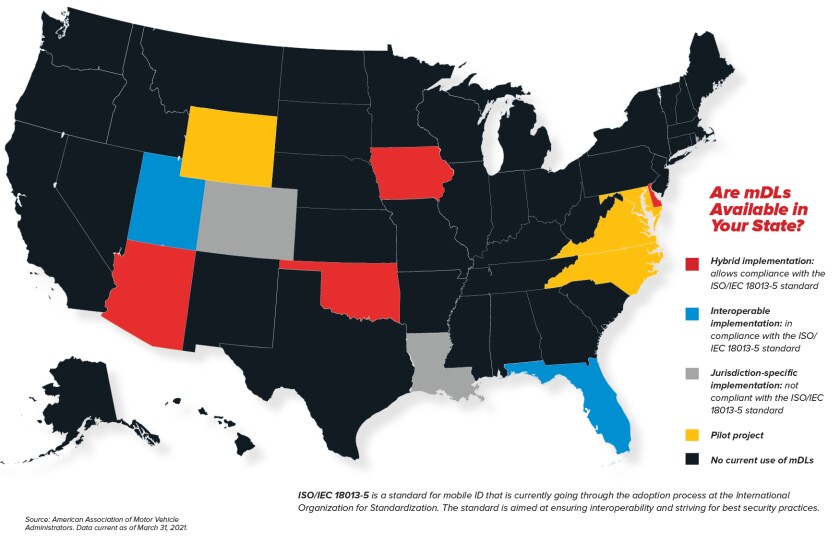

Part of what has made some states hesitant to plunge into mDL work is that standards development has been underway for more than five years. But now an International Standards Organization (ISO) standard is nearing completion. “We’re close enough with it now that we understand what the technical requirements will be,” Thompson said, “and that’s really what’s going to enable the broadest acceptance.”

Another question people have had is how mDLs relate to federal Real ID requirements. Jorgensen says a recently passed Real ID modernization bill made clear that Real IDs could be issued in a mobile format. “There’s still some work that has to be done, and TSA has been actively engaged in trying to develop all the pieces around that,” he said, adding that acceptance at airports would be a key use case for mDLs. “That becomes a great step forward,” he added.

I don’t expect that I will be able to drive anywhere with my mobile driver’s license for probably three to five years. But I do expect to see 15 states issuing mobile driver’s licenses to their residents by the end of 2021.

The ISO standard focuses foremost on the secure exchange of data from the device to the reader, as opposed to a physical representation of the card on the phone, Grossman added. “When you hand over your physical card to somebody, you’re giving them all that information on the cover, when they may not need all that information. An example is every time you use your driver’s license to prove you’re over 21, that person doesn’t need to know your name, your address, or whether you are an organ donor or not. If it’s just an exchange of data that I control, then I could protect my privacy and only give you what is needed to get the transaction done.”

A CONTACTLESS FUTURE

At a very basic level, to get to broader acceptance, people have to be able to use mDLs to drive, so police readers are key. IDEMIA’s Thompson thinks that’s going to take a while because the technology challenge is much bigger as you move down to law enforcement groups in smaller jurisdictions. “IDEMIA is working on how to help law enforcement on the acceptance side. They all recognize that they need to accept it. We all recognize that they don’t want to take people’s devices and people don’t want to hand them their devices,” he explained. “So there needs to be a contactless way of verifying that. That’s going to be a multiyear journey. I don’t expect that I will be able to drive anywhere with my mobile driver’s license for probably three to five years. But I do expect to see 15 states issuing mobile driver’s licenses to their residents by the end of 2021.”

COVID-19, Thompson added, “accelerated literally everyone’s thinking and prioritization of it across the board.”

1.8M mobile driver’s license accounts have been set up in Arizona in the past year.

Even before the pandemic, Arizona could do simple title transfers online using its ID product that was the precursor to the mDL to verify the transaction between the two customers. “We were doing fewer than 100 a month before the pandemic and now we do well over 1,000 every month,” he said.

Simpler notes that Delaware started working on a mobile driver’s license in 2018, two years before the pandemic hit. “We saw an interesting opportunity with the pandemic having hit to talk about the contactless nature of this. So we’ve talked about it being secure and convenient, but all of a sudden that contactless nature became very important in the pandemic in a way that we weren’t anticipating. We absolutely think that the ability to share your identification in a contactless way certainly has driven the adoption rate much higher than we might have anticipated.”

First-year adoption of mDLs in the states that have rolled them out has been slow, but Arizona’s Jorgensen is convinced those numbers will improve over time. “As we find ways to incentivize the adoption by the verifiers, the benefits will become clearer to the public,” he said. “I think that’s coming quick.”

Government Technology is a sister site to Governing. Both are divisions of e.Republic.