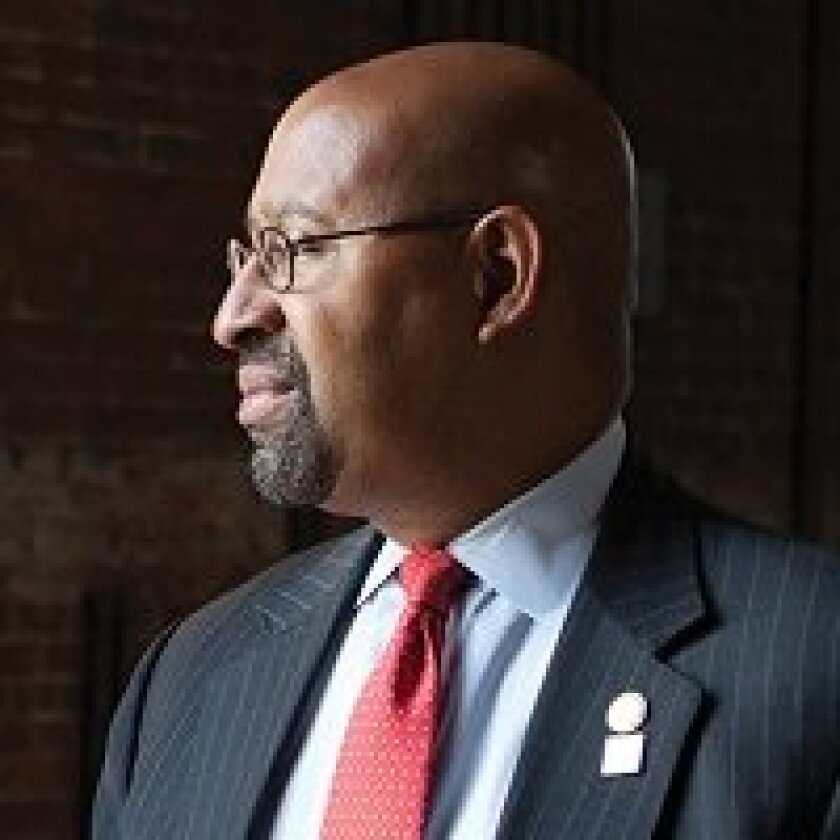

Currently the district’s city administrator, Donahue began his career in 2002 as an entry-level program analyst for the city’s Department of Transportation. Five years later, he took over the city’s performance management portfolio and, in a sentence that devotees of the subject would appreciate, admitted that he “fell in love with the job because it allowed me to really assess whether we're making a difference in people’s lives.”

The performance improvement movement traces its beginning to the breakthrough CompStat years in New York City, when law enforcement utilized innovative technology under Police Commissioner Bill Bratton. Nearly a decade later, in 1999, the “stat” approach had its first civil application with Baltimore Mayor Martin O’Malley’s CitiStat. Yet as the programs have grown up across the country, government users have struggled with how to produce desired outcomes rather than just measuring activities or inputs.

Obviously, some activities are a prerequisite for outcomes, but which and in what dosage is a more complex problem. As deputy mayor of operations for New York Mayor Mike Bloomberg, I was responsible for the city’s very comprehensive performance management scorecard. We would scroll performance highlights on the large screens that surrounded the mayor’s open-office bullpen, and I would constantly see metrics that caused me to wonder whether some of the things we were measuring were actually producing more of the outcomes we wanted.

Now, over a decade later, the data and analytics available to D.C.’s stat program enable an entirely new era of processes and insights. Donahue demonstrated the evolution of those outcome concerns when he discussed a review of 911 emergency calls. He first challenged the activity measure of “speed to respond,” asking if it was really the only critical metric, or even really an outcome at all, especially when not every call warrants an emergency response.

When the district focused on this question, officials made a modification that is now more common in other cities: the use of nurses to divert some of the health crisis calls away from emergency rooms and to primary-care doctors. The 911 center can make the medical appointment on behalf of the caller and arrange for a taxi or ride-share to pick them up; typically, this occurs all on the same day, so the caller doesn't have to wait to see a health professional.

Donahue, however, takes the question of what to measure one level further by looking beyond how many calls are getting diverted to asking, “What are the health outcomes of those diverted individuals?” That question presents another important evolution in the development of performance management: the effort to move from just an agency orientation to outcomes dependent on multiple interventions. This shift to cross-agency outcomes presents both organizational and data challenges, requiring the use of larger and more numerous data sets.

This complex outcome approach is an indispensable part of the future of performance measurement in cities, but the challenges are also immense. This more-refined examination of outcomes, for example, triggers a greater need to protect privacy; in the case of D.C.’s medical diversion program, that includes the use of anonymized Medicaid data to see health outcomes and appointment data from the city’s community health providers.

Any city official who has tried to manage data sharing across agencies can appreciate the frustrations of negotiating with multiple lawyers and administrators who interpret rules in conflicting ways. Donahue says reaching an agreement on the conditions for data use to measure the results of the 911 diversions required months of conversations, which, based on my experience, is a record speed that derives from the fact that a very senior person in the mayor’s office had ultimate authority to make decisions across departments.

Another critical asset available to Donahue, and one which should be copied by other municipalities in dealing with cross-agency outcomes, is The LAB @ DC, a sophisticated group of data analysts that reports to the city administrator and provides rigorous evaluations for projects that span agencies, looking not just at outcomes in general but also analyzing outcomes of multiple different interventions.

Finally, Donahue highlights the indispensable use of spatial analytics as part of the analysis as well as the visualization of performance and equity. The district possesses significant GIS capacity, and it uses those assets to compare performance based on where people live. The ability to visualize performance on maps is visually intuitive and a scientifically rigorous way of understanding and communicating, according to Donahue. GIS, he said, “is a really powerful tool that helps someone who is not a statistician focus in a very intentional way, whether it involves issues of public safety, access to healthy food stores or economic development and access to jobs.”

Donahue’s career and the evolution of stat correspond. From the early days, when he merely furnished performance data, to now, when he consumes it, the field has seen substantial shifts in sophistication. The data tools have improved, and the focus on impacts involving cross-agency action has enhanced government effectiveness. Looking to the future, artificial intelligence technology promises enormous advances for performance management programs, making analyses easier and faster to conduct. Yet to capture these benefits, and indeed transform operational and policy effectiveness, requires what Donahue enjoys: authority from the top of city hall combined with the right questions about outcomes and capabilities.

Governing’s opinion columns reflect the views of their authors and not necessarily those of Governing’s editors or management.

Related Content