(Unique Identification Authority of India)

Despite the digital advances of recent decades, government machinery still tends to run on paperwork and documentation. The burden of dealing with this avalanche of paperwork is not shared equally. While all Americans were eligible for pandemic benefits, the unemployment compensation process was easier to navigate for applicants with education, time, comfort navigating bureaucracy and reliable Internet access.

The pandemic exposed how digital initiatives make assumptions about users, which often exclude those with more unique lives than designers anticipated. Americans are becoming increasingly aware that digital systems often do not equally include those who need them most. That can be fixed. Creating digital equity, one of the topics we explore in our new report on government trends reshaping the post-pandemic world, will require expanding access to digital resources, designing services centered around the user, and building a robust digital infrastructure.

Take online public education. As the pandemic pushed classes to digital platforms, students without reliable access to Internet connectivity and digital devices struggled to catch up. Census data showed that 3.7 million students lacked Internet access and 4.4 million lacked access to a computer. The National Center for Education Statistics reported that 6 percent of students accessed classes solely through smartphones. The nation’s 1.5 million homeless students faced obvious additional challenges. Accordingly, teachers reported that fewer students were performing to grade level.

To address these problems, the Federal Communications Commission asked telecom companies to expand low-cost broadband to students. Federal pandemic-relief legislation provided $16 billion for an Education Stabilization Fund to promote remote learning and improve rural broadband. Across the pond, the United Kingdom’s Department for Education delivered 1.7 million laptops and tablets to children. The agency provided 4G hot spots, acquired free data allowances from telecom business partners, and set up more than 6,000 schools with online education platforms.

Digital equity must be baked in from the start. Silicon Valley’s digital products prioritize simplicity for the user at the expense of complexity behind the scenes. Meanwhile, many government programs place the burden of complexity on citizens, especially marginalized and at-risk groups. The solution: To include marginalized users, design for them.

Human-centric design starts by understanding users. A partnership between New America and the New York state Department of Taxation applied this philosophy to research taxpayers eligible for the federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and a similar state program. The EITC is an effective tool for reducing poverty, but one out of five eligible families don’t even apply. Families who missed this opportunity were more often low income, less educated and non-English speaking. Extensive interviews revealed that target users were intimidated by tax forms. Some recipients even assumed they were in trouble when the IRS asked additional questions or scrutinized their applications. The IRS’ notifications to inform people of EITC eligibility did not communicate the opportunity equally to all recipients.

The partnership recommended dividing potential users into customer segments. Each segment would get a specialized letter emphasizing information relevant to its situation. “One-letter-fits-all generally creates confusion and can lead to decreased readability and responses,” New America wrote. The partnership also suggested sending letters in more languages, with headings and highlights that broke up the documents from IRS legalese into something approaching plain language.

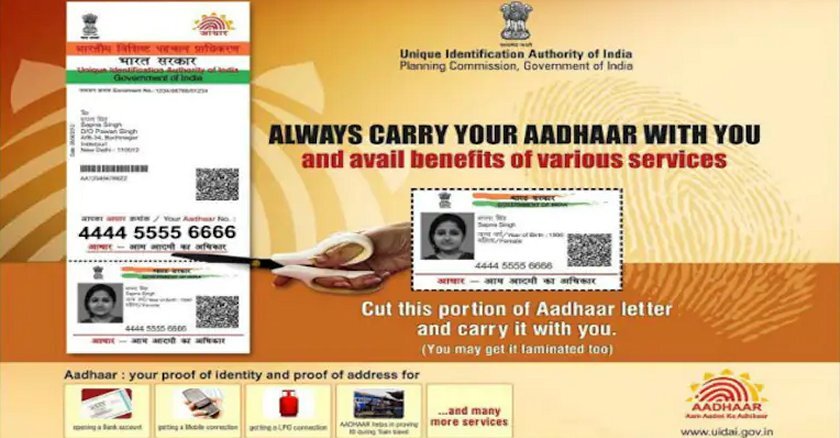

Digital equity can also mean redesigning government programs for a digital environment. Rather than migrate a paperwork system to a website, design for the full potential of digital. Take India’s identity documents. The nation’s multiple identity systems, including passports, voting IDs and tax IDs, were not designed to help deliver government services. To address this challenge, the government created the Unique Identification Authority of India. Each citizen gets a unique digital ID known as an Aadhaar number. It’s recognized across government and can be verified with fingerprints or iris scans. The Aadhaar program has reached 99.5 percent of the Indian adult population.

Furthermore, the IDs connect with individual bank accounts, allowing for direct deposits from government and withdrawals from an extensive network of rural micro ATMs. The system has dramatically cut down on waste and fraud while improving the delivery of benefits directly to citizens. These advances occurred by consolidating the back end of government identity systems, redesigning them for a digital world.

Digital inclusion will require expanding access to the Internet, understanding users, simplifying their experience with human-centric design, and building inclusion into a digital backbone. These tools can open the public sector’s digital initiatives to everyone, making government services more equitable in the process.

Governing's opinion columns reflect the views of their authors and not necessarily those of Governing's editors or management.